Contents

This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2015 by Paul Goldberger

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A.

Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York,

and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a

division of Penguin Random House Ltd., Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered

trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Goldberger, Paul.

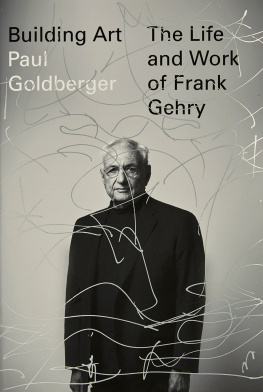

Building art : the life and work of Frank Gehry / by Paul

Goldberger.First Edition.

pages cm

ISBN 9780307701534 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-101-87580-3 (eBook)

1. Gehry, Frank O., 1929 2. ArchitectsUnited States

Biography. I.Title.

NA737.G44G65 2015

720.92dc23

[B] 2015026562

eBook ISBN9781101875803

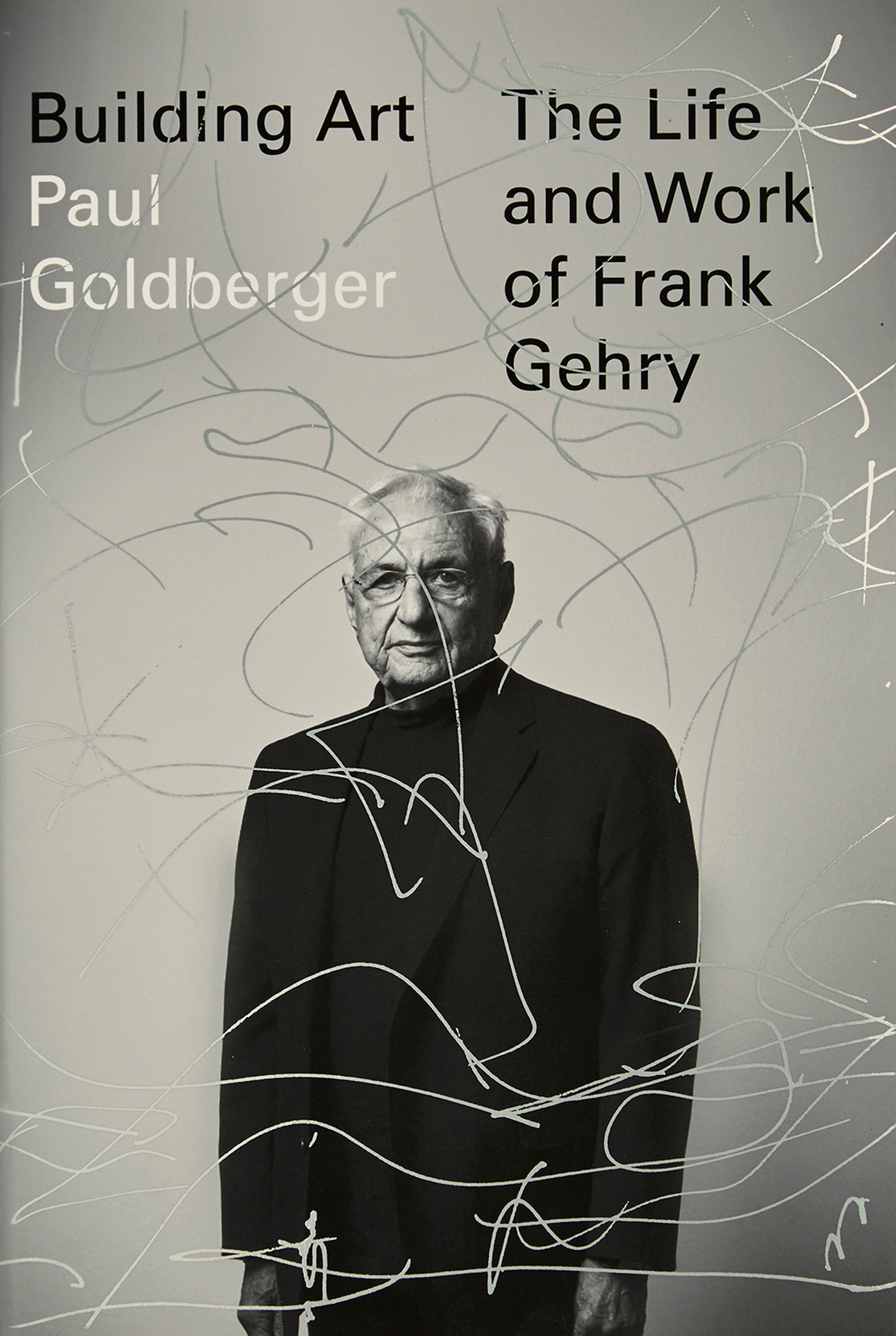

Cover photograph by Lionel Bonaventure/AFP/Getty

Images. Jacket drawings by Frank Gehry. Front: From an early

sketch of Walt Disney Concert Hall; spine: 8 Spruce Street,

New York

Cover design by Peter Mendelsund

First Edition

v4.1

a

For Susan

Rationalists, wearing square hats,

Think, in square rooms,

Looking at the floor,

Looking at the ceiling.

They confine themselves

To right-angled triangles.

If they tried rhomboids,

Cones, waving lines, ellipses

As, for example, the ellipse of the half-moon

Rationalists would wear sombreros.

WALLACE STEVENS, SIX SIGNIFICANT LANDSCAPES, VI

Contents

Preface

I n the spring of 1974, as a young writer for The New York Times, I went to Washington, D.C., for the annual convention of the American Institute of Architects. I didnt normally go to conventions, but I had just become the newspapers junior architecture critic, and I had the thought that attending the largest gathering of architects in the country might be a source of a few good stories, or at least a chance to meet some people and have them meet me. The AIA had just opened its new national headquarters building and wanted to show it off, and as a consequence the big party of the convention was held not in a hotel ballroom but on the grounds of the AIA building on New York Avenue. I was standing at the edge of the party, which spilled out to the sidewalk, talking to my colleague Ada Louise Huxtable, when a pleasant man with a mustache who looked to be in his fortiesI was then in my twentiesrecognized her and came up to say hello.

He, too, seemed an unlikely convention-goer, a bit more casually dressed than most architects, who in the early 1970s tended to look either like insurance salesmen or college professors. This guy had a quiet, eager freshness to his manner. He told Ada Louise that his name was Frank Gehry, and that he was an architect from Los Angeles. His name did not ring a bell; he told us we might have heard of some cardboard furniture he had designed that was sold at Bloomingdales a few years ago, which did seem vaguely familiar, but I certainly didnt know of any buildings he had done. He had a curiosity about our work as journalists, and was interested in criticism and ideas. He told us he was more involved with artists in Los Angeles than with his fellow architects. He did not seem to know many people at the party, and it did not take long to see that he was something of an outlier. But he was not a typical outlier, or he would not have been there at all. He was an outlier who wanted in, but, as I discovered as time went by, on his own terms.

Ada Louise excused herself to return to her hotel, and Frank and I kept talking. That evening began a conversation that has lasted for more than four decades, and this book is one result of it. Gehry invited me to talk further if I ever came to Los Angeles, which I was beginning to do more frequentlyI sensed, more than most New Yorkers, that the city needed to be taken seriously as a laboratory of architecture and urbanism, although I didnt understand at that point how central Frank Gehry would be to what was happening there. But I was happy to come and see some of his work for myself. In 1976 I wrote Studied Slapdash, an essay in The New York Times Magazine about the house Gehry designed for the painter Ron Davis in Malibu, which turned out to be the first time one of his buildings was written about in a national general-interest publication. So I have been documenting his work from a very early point in his career, and an even earlier point in my own.

Over the years, as I came to know and admire his work more fully, and as it grew in both scale and complexity, I wrote about it frequently in The New York Times, The New Yorker, and Vanity Fair, my three professional homes as a journalist and critic. Gehry and I discussed my writing an essay for a monograph on his work at several points; none of these projects came to fruition, but when Alfred A. Knopf proposed to me that I write a full-length biography of himby then he was the most famous architect in the worldI asked if he would be willing to cooperate with me on that project instead of proceeding with the monograph. I said that if he agreed to work with me, it would be necessary to open his archives to me, to discuss the difficult times in his personal and professional life as well as the happy and triumphant ones, and, most important, to agree that he could have no editorial control over the text. He graciously agreed to all of these conditions, and this book is the result.

Night of the Supermoon

T he guest list for the party that Bruce Ratner, a New York City real estate developer, gave in the unfinished seventy-second-floor penthouse of his new apartment tower in Lower Manhattan on the night of March 19, 2011, was unusual for an event celebrating the opening of a new real estate project. The singer and activist Carl Bernstein. These and other famous names had not come to get a preview of the steel-clad building, even though it was then the tallest residential tower in the city and the question of what its apartments would be like had been the subject of much speculative talk around town. Neither were most of the guests friends of Bruce Ratner. The celebritiesand about three hundred other somewhat less recognizable peoplewere friends and acquaintances of a short, somewhat stocky, gray-haired man with glasses, dressed in a black T-shirt and black suit jacket, who spent much of his time standing near the windows on the north side of the penthouse, which had a spectacular view of the Manhattan skyline and the towers of the Brooklyn Bridge. He had designed the building, and he was arguably the most famous architect in the world.

Frank Gehry had turned eighty-two two and a half weeks earlier, and Bruce Ratner decided that a Brooklyn that was to contain seventeen buildings, including a new arena for the Nets basketball team, which was moving to Brooklyn from New Jersey. Gehry had produced an arena design and schemes for several skyscrapers as well as an overall plan, and his involvement gave Atlantic Yards the air of a more serious enterprise than the usual large commercial real estate project. But after winning preliminary approval for the project based on Gehrys plans, Ratner replaced him with another firm and ordered up buildings that were simpler and presumably less expensive than the ones Gehry had designed. Gehry was shaken and angry about the decision, which required him to lay off many of the architects who were working on the project in his office back home in Los Angeles. His frustration was compounded by the fact that he could only express his unhappiness in private, since he was continuing to work on Bruce Ratners tall apartment building for Lower Manhattan, and he could hardly get into a public spat with him. He seethed inwardly, as he usually did when something did not go as he had hoped. He was not fond of confrontation, and he had generally managed to get his way by being friendly and easygoing, not by acting the role of the temperamental artist.