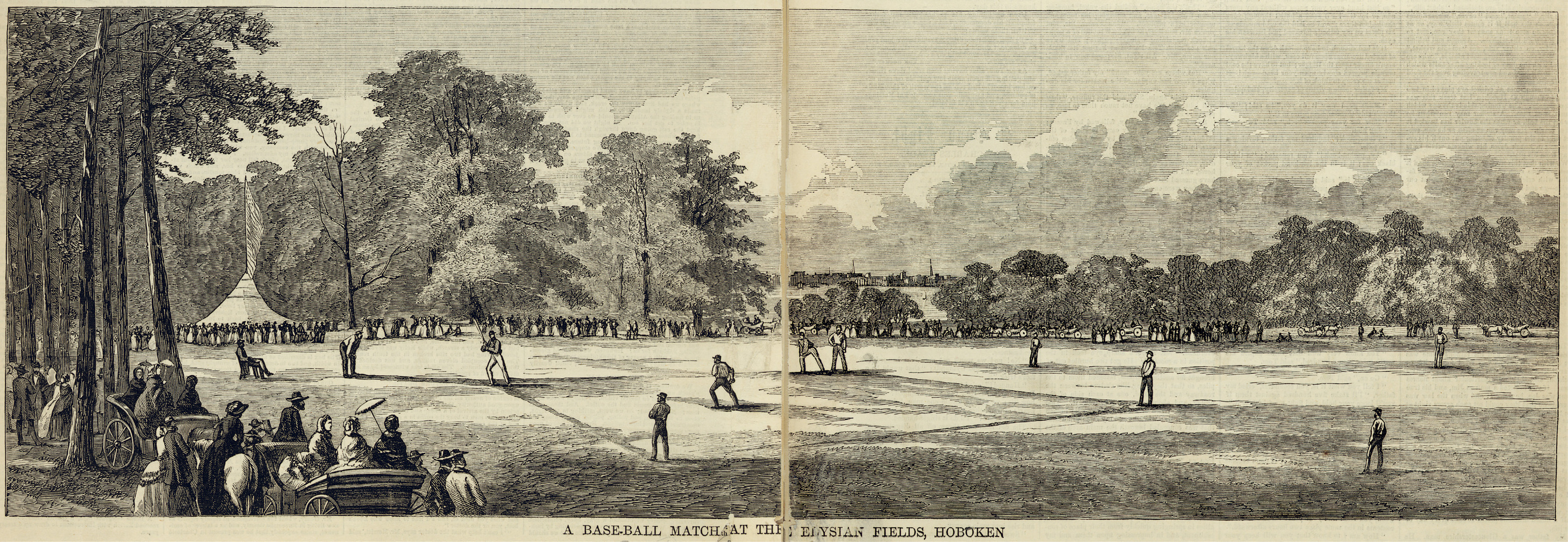

A baseball match at Elysian Fields. Hoboken, New Jersey, 1859

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2019 by Paul Goldberger

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Goldberger, Paul, author.

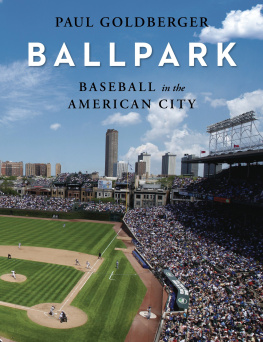

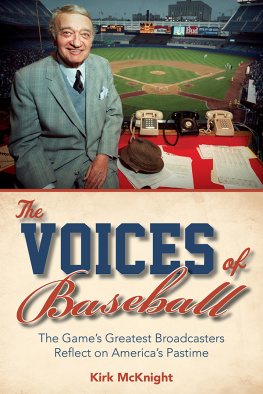

Title: Ballpark : baseball in the American city / Paul Goldberger.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2019. | Includes

bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018046223 (print) | LCCN 2018046867 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780307701541 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525656241 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Baseball fieldsUnited StatesHistory. | Baseball

fieldsUnited StatesDesign and constructionHistory. | Baseball

fieldsSocial aspectsUnited States. | BaseballUnited StatesHistory.

| BISAC: SPORTS & RECREATION / Baseball / History. | ARCHITECTURE /

Buildings / Landmarks & Monuments. | ARCHITECTURE / Buildings / Public,

Commercial & Industrial.

Classification: LCC GV879.5 (ebook) | LCC GV879.5 .G65 2019 (print) | DDC 796.3570973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018046223

Ebook ISBN9780525656241

Cover photograph by Joe Robbins/Getty Images; (sky) Shutterstock

Cover design by John Vorhees

v5.4

ep

For Susan and for all the baseball fans in my familypast, present, and future

Contents

PROLOGUE

Whether in a real city or not, when we enter that simulacrum of a citythe ballparkand we have successfully, usually in a crowd, negotiated the thoroughfares of this special, set-aside city, past the portals, guarded by those who check our fitness and take the special token of admission, past the sellers of food, and vendors of programs, who make their markets and cry their news, and after we ascend the ramp or go through the tunnel and enter the inner core of the little city, we often are struck, at least I am, by the suddenness and fullness of the vision there presented: a green expanse, complete and coherent, shimmering, carefully tended, a garden

A . B ARTLETT G IAMATTI,

T AKE T IME FOR P ARADISE

T HE GAME OF BASEBALL may not truly be the ultimate American metaphorthe attempts to make it so tend to be exaggerated, sentimental, and mawkishbut the baseball park, the expanse of green that begins beside city streets and appears to extend forever, is. It is not only that it is a simulacrum of a city, as A. Bartlett Giamatti, the scholar of literature and baseball who served as both president of the National League and commissioner of baseball, wrote. It is also that it contains a garden at its heart, and as such it evokes the tension between the rural and the urban that has existed throughout American history. In the ballpark, the two sides of the American characterthe Jeffersonian impulse toward open space and rural expanse, and the Hamiltonian belief in the city and in industrial infrastructureare joined, and cannot be torn apart. They no longer represent two alternative visions of the world, as they so often do. In the baseball park, they each need the other. They must coexist. The exquisite garden of the baseball field without the structure around it would be just a rural meadow, bereft not only of the spectators themselves but of the transformative energy they bring. And the stands without the diamond and the outfield would be a pointless construction.

In the baseball park we can see how this country expressed a concept of community, and how we imbued the public realm with shared meaning. The baseball park was always a special kind of place, usually privately built and privately owned but able to instill people with a greater sense that it belonged to them than most places that had been built by their government: this garden in the center of the city, this piece of rus in urbe, was spiritually public if legally private, and in almost every city it formed a defining element of the civic realm. As much as the town square, the street, the park, and the plaza, the baseball park is a key part of American public space.

We can see through baseball parks how Americans went from viewing their cities as central to the idea of community in the first decades of the twentieth century to wanting to run away from them in the decades after World War II, and then how we have tried in our own time to use baseball parks to get our cities back. The first generation of ballparks, places like Union Grounds and Washington Park in Brooklyn and South End Grounds in Boston and Sportsmans Park in St. Louis, as well as the ornate and marvelously named Palace of the Fans in Cincinnati and the still larger Ebbets Field and Fenway Park and Wrigley Field that followed not far behind, grew out of neighborhoods, took their eccentric forms from the pattern of city streets, and were inextricably tied to their surroundings. The story of Ebbets Field is the story of Brooklyn, as the story of Tiger Stadium is the story of downtown Detroit.

The second generation of ballparks, places like Shea Stadium, is a different story: concrete bunkers, often circular, shaped not by the grid of urban streets but by a backward glance to the ancient Colosseum, an amphitheater built for gladiators, not pitching duels. (Not by accident, perhaps, were many of them designed to do double duty as football stadiums.) Set in a sea of parking, these ballparks were generally built during the years after World War II to escape the city, or at least to minimize any connection to it, and they were invariably suburban in concept if not in geography. They reveal how far Americans had come in the postwar years from thinking of urban neighborhoods as desirable turf. The most famous of the postwar structures built for baseball, the Astrodome, had a roof that rendered the entire ball field interior space, removing even the fig leaf of rus in the urbe. And the Astrodome was far from the only ballpark whose builders thought baseball would be better off played on artificial turf under a huge dome than on grass under the sky.

And the story changes again with the ballparks of the third generation. Beginning in 1992 with Oriole Park at Camden Yards in Baltimore, new ballparks in cities across the country brought baseball back to its downtown origins, often, as at Camden Yards, quite literally integrated into older urban neighborhoods, and returning to the field of grass under the open sky. (A few recent ballparks have had retractable roofs, very different from permanent domes; they use technology as a means of avoiding rain postponements, not of cutting all play off from nature.) But what is most important about the ballparks of the third generation is that most of them were designed in the hope of weaving together an urban fabric that had been broken, aspiring to use baseball to heal the city rather than to run away from it.