The entrance to Robin Boyds house is via anopen-tread wooden staircase sited under a protective canvas awning.

A WORD FROM PENELOPE SEIDLER AM LFRAIA

The houses that feature in the following pages, as selected by Karen McCartney, represent the grand variety that flourished in Australian post-World War II architecture. It is heartening that the first edition of the book was treasured by so many to warrant the demand for another printing, bringing it to a wider audience.

For the most part, the houses here are simple family homes, with timeless design integrity, happily lacking the pretension and pseudo stylistic features that characterise much contemporary design. They are each a time capsule of their era. They also have a connection, in one way or another, with the landscape. Perhaps more than anything else, this is what identifies that period. With the end of the war came the breaking down of many boundaries and an awareness and engagement with the outdoors: youll see many large glass areas, blurring the edges between inside and out, along with large balconies for outdoor living. Interiors were opened up, with space flowing between the interior and exterior, as well as between rooms, rather than the boxed rooms and corridors that were present in earlier architecture. Of the fifteen architects included in the book, all are males, and four are immigrants who were educated overseas. All of the houses, however, are Australian.

It is unfortunate that many houses of the era have been demolished or grossly altered, only to be replaced by overbearing mansions with fake columns and arches and no design integrity. It is to be hoped that with the communitys increasing awareness of the Copyright Amendment (Moral Rights) Act of December 2000, any owners wishing to upgrade their property will need to do so in consultation with the original architect or their estate, thereby maintaining the architectural integrity.

Harry Seidler, writing in the Bulletin in October 1989, said of the Australian style that it is the successful response to the climate and our informal way of life, rather than an identifiable style. Nowhere is this better illustrated than in the diverse range of houses depicted in this book. Karen McCartney is to be congratulated for gathering these houses together in this beautiful book, sharing the enjoyment that they bring with a wider audience and preserving them in these pages.

A cantilevered cabinet in a bedroom of Hugh Buhrichs house in Sydneys Castlecrag.

CONTENTS

THE AUDETTE HOUSE / PETER MULLER

THE GROUNDS HOUSE / ROY GROUNDS

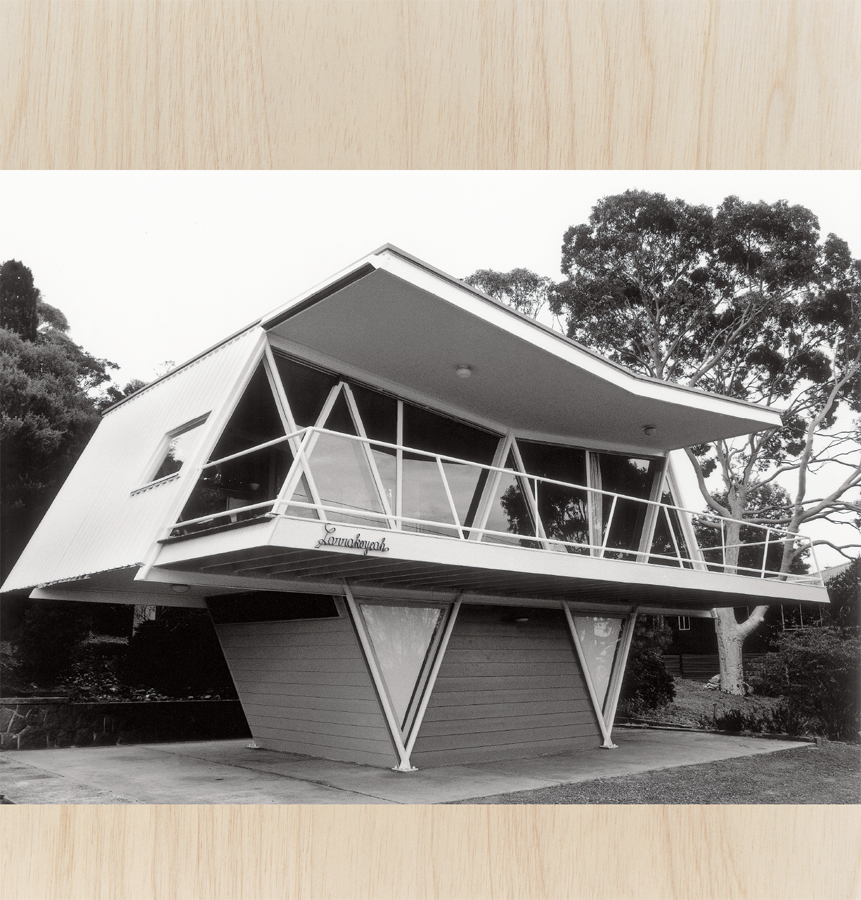

THE BUTTERFLY HOUSE / PETER McINTYRE

THE JACK HOUSE / RUSSELL JACK

THE WALSH STREET HOUSE / ROBIN BOYD

THE GRIMWADE HOUSE / DAVID McGLASHAN AND NEIL EVERIST

THE DINGLE HOUSE / ENRICO TAGLIETTI

THE ROSENBURG / HILLS HOUSE / NEVILLE GRUZMAN

THE MARSHALL HOUSE / BRUCE RICKARD

THE BUHRICH HOUSE II / HUGH BUHRICH

THE LOBSTER BAY HOUSE / IAN McKAY

THE KESSELL HOUSE / IWAN IWANOFF

THE KENNY HOUSE / JOHN KENNY

THE COLLINS HOUSE / IAN COLLINS

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

The McCraith House was designed by Melbourne architects Chancellor and Patrick. A compact holiday house in Dromana, a coastal town outside Melbourne, it illustrates the preoccupation with geometry prevalent at the time. Originally decked out in primary colours, it was later painted a more muted shade.

Many of todays new houses are designed with a level of indulgence and luxurious use of space that could not have been imagined 60 years ago. Media rooms, multiple bathrooms with spa-style fittings, music rooms, in-house gymnasiums and swimming pools were once the territory of the rich industrialist rather than someone in middle management. Hence it is hard from this position of prosperity to conceive of the level of limitation Australians experienced in the postwar years. Nothing was thrown away nor taken for granted. Clothes were handed down, furniture was fixed, food continued to be rationed the mend and make-do mentality pervaded every aspect of life.

The war years (193945) were particularly grim for the architectural profession, and many small firms closed through lack of work. Materials were scarce and domestic buildings were subject to strict guidelines in terms of expenditure and size. The maximum floor space allowed was 14 squares (135) and an Australian Home Beautiful editorial in 1942 pointed to maximum costs of 3000 for a new house and a ceiling of 250 on renovations. These restrictions continued in the postwar years and, because of thedesperate need for housing with the wave of new migrants and the numbers of returned servicemen, the drive was often for quantity over quality. Aesthetics tended to give way to economics as the state controlled the entire process; the architects, engineers, designers and town planners all fell under one great bureaucratic umbrella.

An estimated 400,000 homes were needed, and to solve the housing crisis, the government looked both to local and overseas companies for quick-to-assemble housing. The Commonwealth Government (in conjunction with private enterprise) undertook a fact-finding mission to Europe to source the most suitable housing options, and subsequently bought prefab housing from Sweden and Great Britain. In his book Australian Architecture 1901 51, Sources of Modernism, Donald Leslie Johnson notes that probably the largest order for English prefabs came from the Australian government when it purchased a batch of factory made timber dwellings called the Riley-Newsum house as late as 1951: cost of 1,250,000 pounds sterling. Made in Lincoln and shipped to Australia in a series of panels.

Set out in neat quarter acre suburban blocks, these houses had few of the refinements of previous decades, as Jennifer Taylor describes in her essay Beyond the 1950s: The design features that had made the bungalow such a suitable building type for the 1930s and 1940s could no longer be achieved under the restrictions. Luxuries such as eaves, porches, verandas and fireplaces disappeared. In its stripped down form the Australian house had few redeeming qualities.

The arrangement of rooms also reflected a bygone era. The living room and master bedroom faced the street and corridors led to a separate kitchen and dining room, while the rear of the building housed the bathroom and laundry with access to the yard. Basically, the plan consisted of boxy rooms with little thought given to either the relationship between them, or to the linkbetween indoor and outdoor space. Orientation was a given the house faced the street regardless of sun or site.

While this was true of the broad sweep of development, there were exceptions. It was a time where young architects felt a sense of opportunity to build a better world and there were ingenious plans by some, working within the restrictions, to maximise the sense of space by losing wasteful corridors and opening up kitchen and dining rooms to one larger area. Notable is theBeaufort House, designed by Arthur Baldwinson in conjunction with the Beaufort Division of the Department of Aircraft Production, which was shown in prototype to the public in 1946. Using technology developed for aircraft manufacture, this steel framed house was an innovative attempt to contribute to solving the housing problem. The Vandyke Brothers in Sydney also provided local product with, amongst more traditional designs, the Sectionist house, created in 1946.