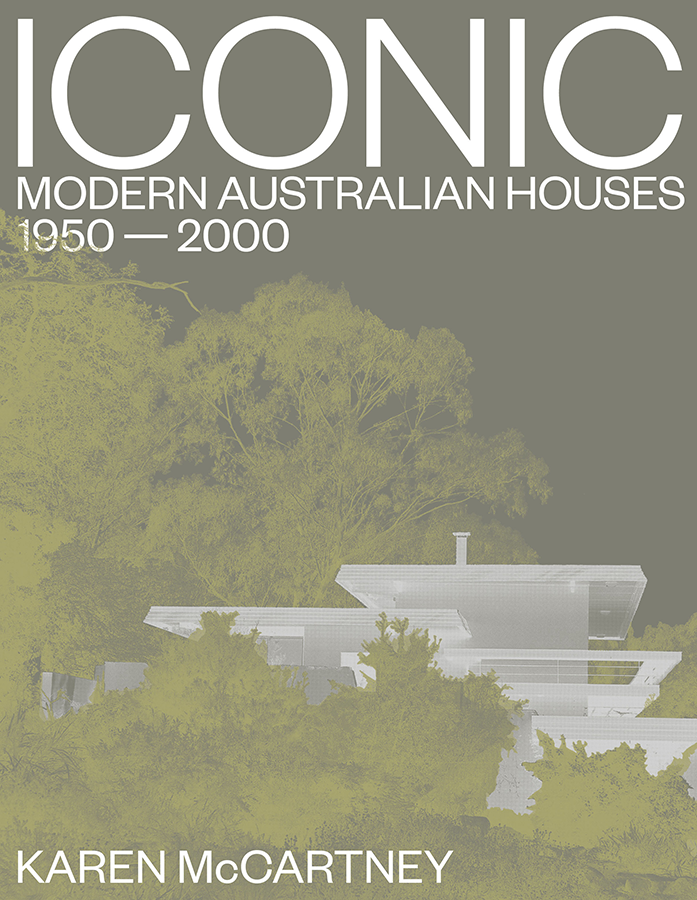

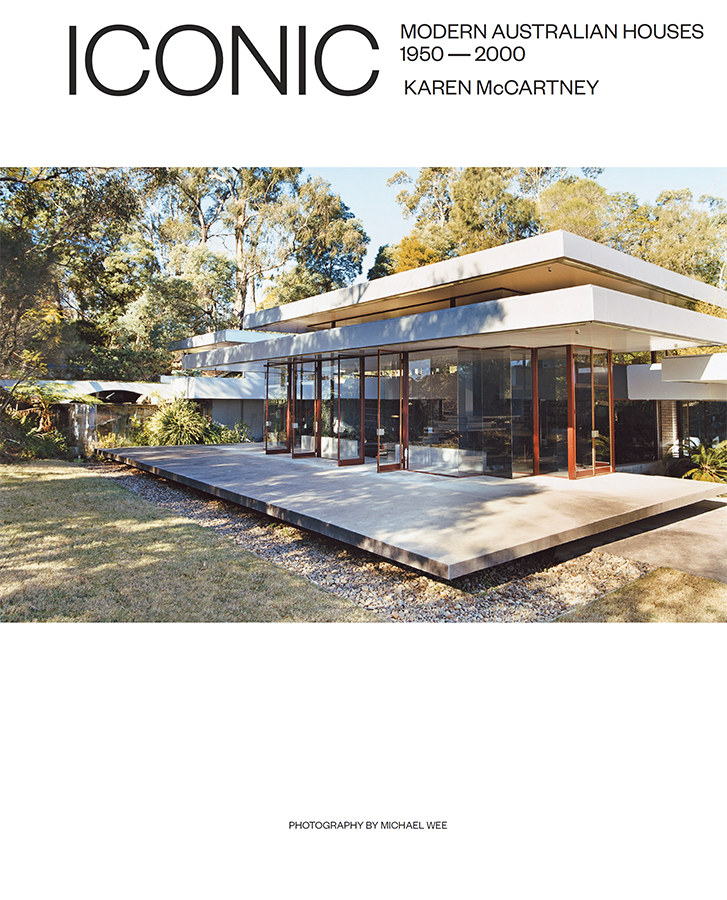

Karen McCartneys Iconic Australian Houses books are re-imagined so cleverly in this freshly designed, encyclopaedic book, which brings together in one volume the best of 50 years in Australian residential architecture.

Lucy Feagins, The Design Files

| Harry Seidler | Iwan Iwanoff |

| Peter Muller | Ian Collins |

| Roy Grounds | Daryl Jackson |

| Peter McIntyre | Barrie Marshall |

| Russell Jack | Ken Woolley |

| Robin Boyd | Robinson Chen |

| McGlashan and Everist | Gabriel Poole |

| Enrico Taglietti | Wood Marsh |

| Neville Gruzman | Andresen OGorman |

| Bruce Rickard | Durbach Block |

| Hugh Buhrich | Sean Godsell |

| Ian McKay | Stutchbury and Harper |

| Richard Leplastrier | Donovan Hill |

| Glenn Murcutt |

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In 2000, we moved as a family into Bruce Rickards Marshall House (1967) in Sydneys Clontarf. For me, it kickstarted an interest in residential Australian architecture from the 1950s onwards, which resulted in two books 50/60/70 Iconic Australian Houses , published in 2007, and its follow-up, 70/80/90 Iconic Australian Houses in 2011. The 1970s features twice, as I managed to get two of the most influential houses of the period for the second book, the Kempsey House by Glenn Murcutt and the Palm House by Richard Leplastrier. The books formed the core content for a Sydney Living Museums exhibition which, for four years, travelled Australia-wide, and included not only images and text, plus video interviews with the architects and home owners, and selected models of the houses.

It is time to revisit these two volumes, to draw them into one book, redesign them in a new format and add one that got away the first time the Jackson House, by Daryl Jackson in Victoria.

Part of the interest in these houses is the architectural lessons they provide: often modest in scale, they are inventive with site, materials and floor plan. The relationship to the outdoors starts tentatively, but gradually opens up to fully integrate gardens, courtyards and verandahs. This response to place, which began in the 1950s, is different to the 1940s where the model was British, with important rooms to the street front and a lack of connection to the back garden.

In the 10 years after World War II, more than 1.5 million migrants arrived in Australia; combine that with the numbers of returned servicemen, and there was a desperate need for housing. Building materials were scarce, and houses were subject to strict guidelines in terms of expenditure and size. The drive was often for quantity over quality, and aesthetics tended to give way to economics as the state controlled the process; architects, engineers, designers and town planners all fell under one bureaucratic umbrella.

To solve the housing crisis, the government looked to local as well as overseas companies, in Sweden and Great Britain, for quick-to-assemble housing. Set out in quarter-acre blocks, these houses had few of the refinements of previous decades the plan consisted of boxy rooms with little thought given to the relationship between them, or to the link between indoor and outdoor space. Orientation was a given the house faced the street regardless of sun or site.

While this was true of the broad sweep of development, it was also a time where young architects attempted to build a better world. There were plans by some, working within the restrictions, to maximise the sense of space by losing corridors and opening up kitchens and dining rooms. Notable is the Beaufort House, designed by Arthur Baldwinson in conjunction with the Beaufort Division of the Department of Aircraft Production, which was shown in prototype to the public in 1946. Using technology developed for aircraft manufacture, this steel-framed house was an innovative attempt to contribute to solving the housing problem.

THE SPIRIT OF THE FIFTIES

The arrival of the Fifties, with its economic prosperity, brought optimism and a strong consumer drive. Putting the war years behind them, Australians wanted the latest in mod cons and a style of home that reflected the spirit of the times. Magazines such as Australian Home Beautiful and House & Garden drove trends and influenced opinion. For a society that had made do, the desire for this new, ordered suburban life was irresistible. It is understandable that the state-of the-art kitchen at the Rose Seidler House, with its cutting-edge appliances, caused as much excitement as the radical building itself.

The Age RVIA Small Homes Service in Melbourne, launched in 1947, with Robin Boyd as director, showcased 40 architect-designed plans for homes that could be bought for 5. By 1951, they were providing plans for 10 percent of all new housing in Victoria. From 1957, plans were also available at the Home Plan Service Bureau at the Myer Emporium, Melbourne, and in 1962, Lend Leases Carlingford Homes Fair in Sydney proved popular to the tune of two million visitors eager to see the latest in architect-designed project homes. This later morphed into Pettit & Sevitt, a company that, by 1963, was selling more than 200 houses per year. House plans were even published alongside knitting patterns in The Australian Womens Weekly .

A CRADLE OF MODERNITY

Postwar was a period of staggering creativity in Melbourne. Young architects were experimenting with shape and materials Peter McIntyre, for instance, built his own house, an A-frame steel structure, with infill panels of Stramit, a compacted straw sheet material. A shortage of materials had seen the introduction of lightweight steel frames and, as in Kevin Borlands Rice House, a series of thin concrete-sprayed shells. Cantilevered balconies and window walls; cable supports and plywood ceilings; colour and form; playfulness and theatre experimentation knew no bounds.

A newly found affluence resulted in an interest in the holiday house. At one end of the spectrum was the commission from John and Sunday Reed for architects McGlashan and Everist to design a house right on the sand at Aspendale, a suburb outside Melbourne. At the opposite end, advertisements incorporating plans appealed to home builders to buy sheeting material and construct beach shacks themselves.

Another prominent architect designing beach houses (as well as country properties and city residences) in the Fifties for wealthy Melbourne clients was Guilford Bell, who had trained in London in the 1930s where he worked on a house restoration project for author Agatha Christie.

Melbournes virtuoso performance was, however, short-lived. As Peter McIntyre admitted, it is hard to make a living out of radical thinking but, for a time, it was, as Robin Boyd said, Australias cradle of modernity.

TESTING POPULAR TASTE

In Sydney, an early pioneer of modernism was Sydney Ancher. He had spent time in Europe in the Thirties and returned to Australia filled with enthusiasm for the work of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. In 1937, he designed what is considered one of Sydneys most important prewar buildings, the Prevost House, for his architectural partner Reginald Prevost. Anchers experiences with local councils reveal something of the attitudes towards the new thinking in architecture. The 1945 design for his own house, Poyntzfield, in Killara, Sydney, was only approved after he altered the plan for a steel-framed building to a more traditional brick construction with a pitched roof. It still won the Sulman Medal in 1946.