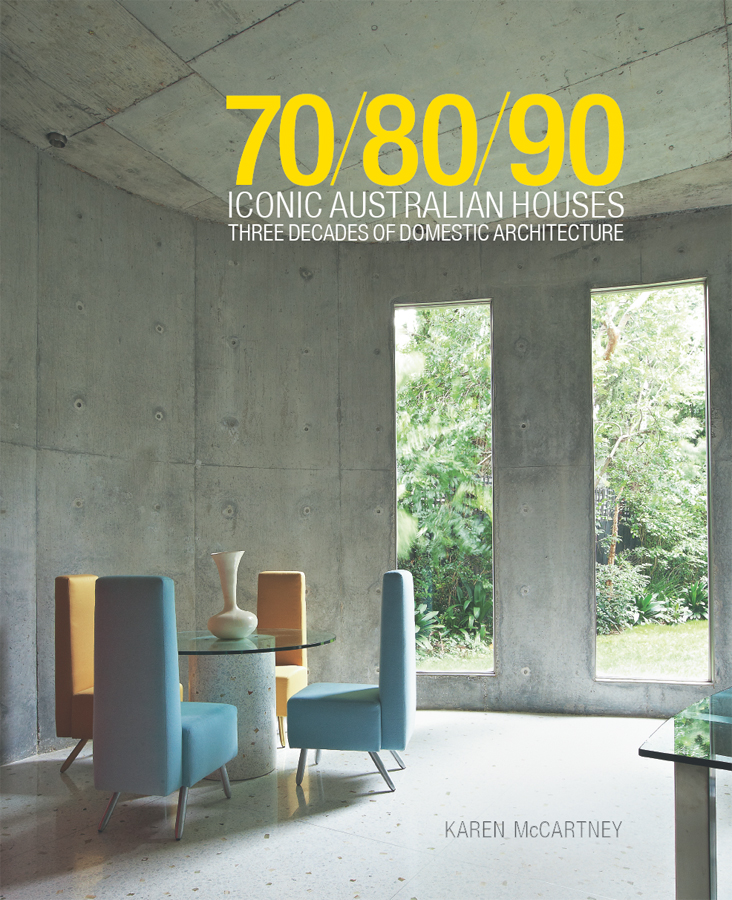

KAREN McCARTNEY has a wealth of experience in the areas of design, art and style, spanning 20 years and several continents. With an honours degree in the History of Art and English from University College, London, her first job was on British magazine Art Monthly. From there, Karens passion for mid-century modern furniture, interiors and contemporary art has seen her rise through the ranks of the worlds prestige media. She has written for, among other titles, British Elle Decoration and The Financial Times. In Australia she edited Marie Claire Lifestyle before becoming founding editor of interiors magazine Inside Out in 2000. Married with two children, she lives on Sydneys North Shore and is Group Editorial Director at News Magazines.

1973 was a momentous year for Australian architecture. After almost two decades of turmoil, controversy and anticipation, the Sydney Opera House was opened by the Queen in October, putting Australia on the world design map in the most spectacular of ways. In the same year and in the same city, but with no fanfare whatsoever, another groundbreaking building was completed. With walls of canvas and a roof like a pair of upturned rowing sculls, Richard Leplastriers Palm House was unlike any other in the country. Hidden from the street, it is as private as the Opera House is public, but its sense of place and sensitivity of design have helped make it an enduring favourite among architects both nationally and abroad.

The Palm House is just one of the significant houses, many of which have not been comprehensively documented before, that author Karen McCartney examines in 70/80/90 Iconic Australian Houses. Focusing on fourteen celebrated designs, McCartney looks at each house in turn, interviewing both architects and owners, and setting their insights and reminiscences within a broader context. She discovers the influence of international greats, such as Le Corbusier, Alvar Aalto, Kenzo Tange and Louis Kahn, as well as the more personal mentorship given by earlier generations of Australias best on the architects featured, and their deep respect for the unique, often hostile, local landscape.

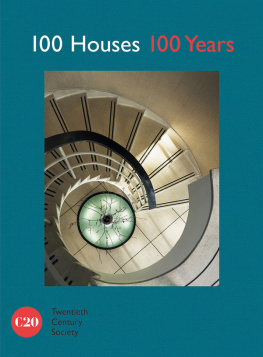

Each house study contains plans and an illustrated description of specific details associated with the architecture and interior design, focusing on such aspects as furniture, fixtures and materials. Superbly designed and richly illustrated with photographs by Michael Wee, 70/80/90 Iconic Australian Houses and its companion volume, 50/60/70 Iconic Houses (Murdoch Books 2007), provide a unique and invaluable guide for everyone interested in contemporary Australian architecture.

This book is dedicated to David, Mac and Ava.

CONTENTS

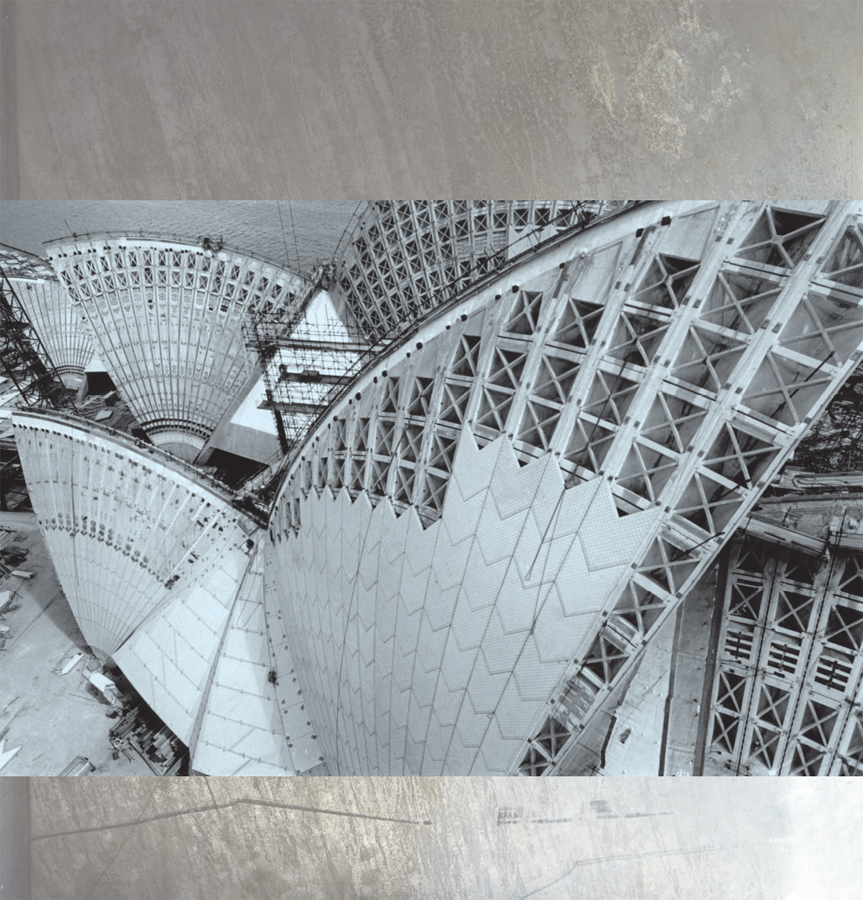

Sydney Opera House roof geometry, photographed by David Moore in 1966 clearly shows the construction of the shells and how the roof tiling was resolved after much experimentation.

INTRODUCTION

I LIKE TO BE ABSOLUTELY MODERN AND WORK AT THE EDGE OF THE POSSIBLE. JRN UTZON

THESE SAILS WERE SLOWLY GROWING increment by increment, and when a friend of mine got a job with Utzon, I thought if he can, I can, says Richard Leplastrier on witnessing the awe-inspiring structure of the Sydney Opera House begin to take shape. He wrote to Jrn Utzon and before long was part of his team, which comprised a handful of architects from Utzons office in Denmark and a cluster of young Australian graduate architects, like Leplastrier and Peter Myers, who had the mental agility and passion to work on the project.

There are many buildings in this book that have come about almost by chance fates sleight of hand in a different direction, and they would never have happened at all. This is also true of the Sydney Opera House, the foundations of which were laid in a city that, in spite of the post-war influx of European migrants, felt remote and removed from the vanguard of world architecture.

Much is made of international judge, Eero Saarinen, arriving late, and supposedly pulling the Utzon design from a pile of rejects. What is probably more accurate is Saarinens belief in the feasibility of the design when one takes a look at his TWA Terminal at New Yorks JFK Airport (formerly Idlewild), his understanding of engineering advances that enable the roofline to be liberated is clear. The statement from the jurors in The Sydney Morning Herald on January 30, 1957 reads: Because of its very originality it is clearly a controversial design. We are, however, absolutely convinced about its merits. It also, ironically, had a bold pull-quote, as part of the article, saying, Cheapest to build.

We now know it wasnt the initial, rather nave, estimate of 7 million dollars blew out to an eventual 102 million dollars by 1973 (the Opera House Lottery was set up to partly pay for it the last one was drawn in 1986). Utzon, the son of a naval architect with boatbuilding in his blood, once said, I like to be absolutely modern and work at the edge of the possible. That worked for a while, with many of the young Australian architects working on the project feeling completely invincible while the experimental Danish architect was in charge. But a change of State Government saw him forced to resign, leaving Australia in 1966, never to return. Australian architects led by Peter Hall finished the job, and when the Queen officially opened the building in 1973, Utzons name was not mentioned.

Graham Jahn, in his book Sydney Architecture notes that the scheme makes no reference to history or to classic architectural forms, and adds, The organic shape and lack of surface decoration have made it both timeless and ageless.

Its sculptural form ensures it has become one of our primary national symbols, which, even when reduced to a mere artists squiggle, still has the power, and the resonance, to say Sydney. In an age where brands are global currency, it has transcended its physical state and become a positive emblem for Sydney and, by default, Australia.

Sun patterns within the Sydney Opera House podium, photographed by David Moore in 1962, illustrates the intrinsic beauty and poetry of the building even during the early days of construction.

THE NEW RURAL

Like many great works of art it was ahead of its time and while Utzons personality inspired a number of Australian architects, it did not produce a corresponding aesthetic. For Richard Leplastrier it was Utzons lack of prejudice, his sensitivity to nature and his openness to new ideas that he appreciated and appropriated. By the time the Sydney Opera House opened, Leplastrier and Glenn Murcutt were beginning work on their groundbreaking projects the Palm House on Sydneys Northern Beaches and the Kempsey House, in rural New South Wales.

These projects were rarefied one-offs made possible by a close working relationship with enlightened clients. The discreet approach of Leplastriers house meant it was only seen by an admiring handful, and its lack of exposure has added to its mystique over the years. Murcutts Kempsey House, on the other hand, received a significant amount of press and public attention. While the less architecturally savvy might have labelled it a shed, albeit an elegant one, the profession could appreciate its Miesian floor plan and underpinning of modernism. The public, in turn, could identify with its form and materials. There was something familiar to hold onto and within the context of the vernacular, the floor plan didnt seem so challenging. Its rural setting and its honesty of construction anchored it squarely in the bush, which resonated broadly with Australians.