Architects Houses features the homes ofthe following leading Australian architectsand designers:

Domenic Alvaro

Rob Brown + Caroline Casey

Sue Carr

Clare Cousins

John Denton

Philip Goad

Simon Hanson

Drew Heath

John Henry

Stephen Jolson

David Luck

McBride Charles Ryan

Randal Marsh

Sam Marshall + Liane Rossler

Ian Moore

Rachel Nolan

Richard Peters + Heidi Dokulil

Dennis Rabinowitz

Kerstin Thompson

Brian Zulaikha

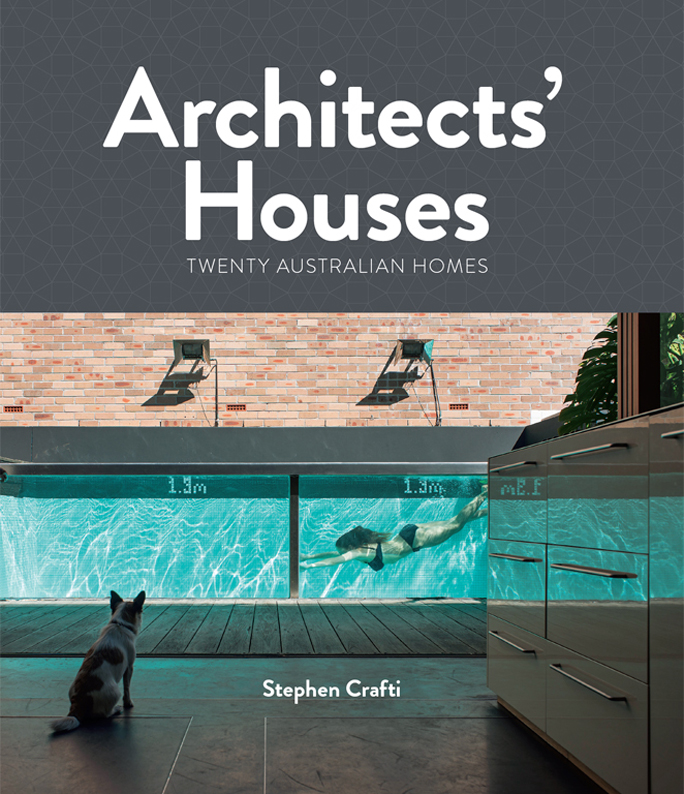

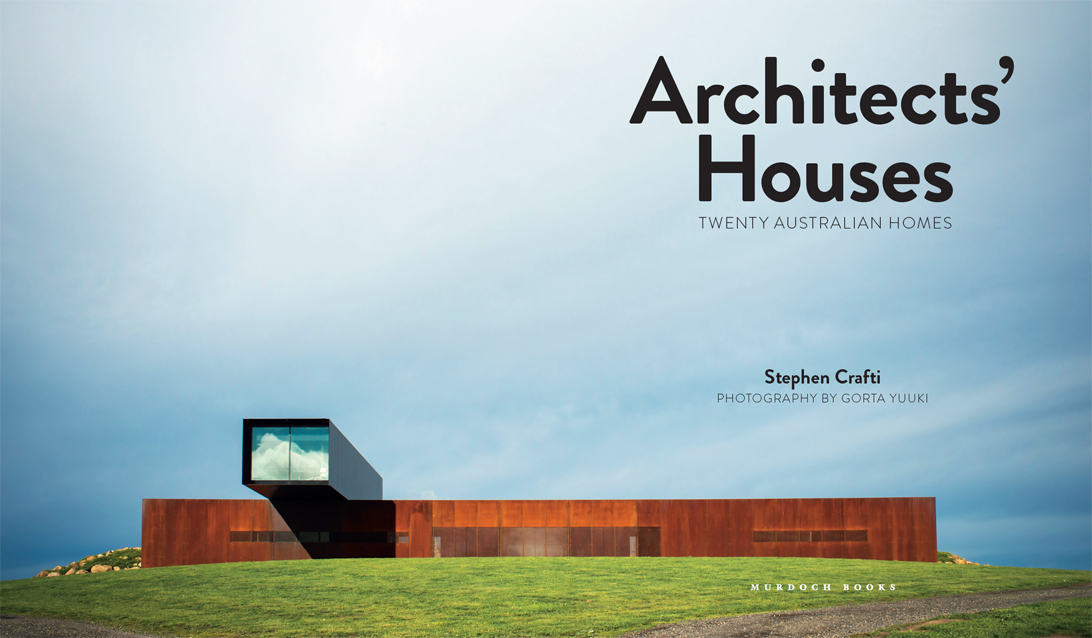

Cover:

The glass-fronted pool beyond the living area in Simon Hansons home.

Contents

Sam Marshall

Liane Rossler

A sense of optimism |

Richard Peters

Heidi Dokulil

The shed |

Introduction

Sue Carrs home office occupies a nook below the staircase.

The dream for most architects is to design their own home. After years of designing homes for others, to finally have the freedom to create something of their own could be considered the ultimate reward. However, being given this relatively open brief must also be challenging.

This book features homes by leading Australian architects and designers. Their designs are diverse, from converted warehouses to penthouse apartments with water views. Each project came with its own challenges and faced its own constraints, whether it was the site or the budget. However, I felt it was important to show diversity in the way architects live, from the simple cottage, to the large monumental statement.

Some of the homes featured in this book have recently been completed, while other projects have evolved over a number of years. Unlike the home specifically designed for a client, with a finite completion date, architects own homes are rarely, if ever, finished at least to their satisfaction. Changes are always being made and, sometimes, theyre a work in progress. Architect/builder Drew Heath, for example, isnt fussed by cupboards that still havent been detailed. Its something that he will get to when he has the time. Likewise, architect Rob Brown intends to paint the faade of his fibro cement home. Its on a list of things to do, but the peeling paint doesnt overly concern him. Other architects, such as Sue Carr, arent the type to live with things that are incomplete. Everything in Carrs house is completed and detailed to perfection.

Although when architects design their own homes there isnt the traditional client to account for, there are other clients in the wings, be they their family, or simply the architect themselves. What are their priorities? And how are these realised? In the case of some architects featured in this book, the client is their partner. Others are allowed complete freedom to fully realise their dream. Architect John Henry, for example, wanted to live in a warehouse-style home, complete with a dirt floor. Evocative of Robin Boyds Featherston house designed in 1967, its a challenging house to live in during the extremes of the year, be it winter or summer. At these times, Henrys partner, Deb Ganderton, prefers to stay in their city apartment, where heating and cooling is within a more even range.

One thing revealed in this book is that architects design their homes just for themselves, rather than having the word resale in the forefront of their minds. Architect Kerstin Thompson, for example, has only one bathroom in her warehouse-style home. Shared by three people, its conveniently placed next to the two bedrooms. The idea of a guest powder room doesnt seem important in the scheme of things. Whats more important to Thompson is a large dining table where family and friends come together. On the other hand, architect John Henry has a separate powder room for guests, enclosed and concealed below the main bedroom. But his own ensuite is simply a shower rose attached to a mirrored wall, completely open to the mezzanine-style bedroom. His partner, Deb, was initially concerned with this set-up. But she realised he wanted to take his design to places where regular clients would seldom venture.

As well as showing how architects have realised their own dreams, this book will hopefully encourage people to test their own boundaries and see living in a different way. For example, architect Simon Hanson shows how a family of five can live in a relatively small home. His small terrace, which doesnt present itself as a family home, is opened up in ways that make this possible. Theres only one bathroom, the parents wardrobe is located in another bedroom and two of the children share an attic-style bedroom. But theres still sufficient room for a swimming pool in the compact backyard. The children use the laneway next to the house as an extension of their backyard. A park at the end of the narrow street offers more outdoor space.

Architect John Henrys warehouse-style home is enlivened by colourful furniture and paintings.

Architectural writer and architect Philip Goad was extremely mindful of preserving the qualities of his late 1920s home, designed by architect Eric Nicholls. Unlike some people, who would have renovated the home and put in a new kitchen and, most likely, ensuite bathrooms, Goad respected the past. The one and only original bathroom remains virtually intact. The kitchen, about 2.5 x 2.5 m (8 x 8 ft) just enough room for standing), has been only slightly modified. A new stainless steel sink, fashioned in the original design, has been installed, together with a new commercial stainless steel oven and stove. But the kitchen is more than adequate for the familys needs. And, rather than change the proportions of the original house, a new detached wing containing another bedroom and study, was designed and built in the back garden.

While some architects featured in this book live in large homes, many occupy small footprints. Designer Richard Peters, for example, lives in a modest warehouse, with one open-plan kitchen, dining and living space. The only outdoor areas are a light well, which is adjacent to the dining area and slivers of space adjacent to the two bedrooms. However, theres a patch of land directly opposite their laneway, used as a vegetable garden. And, as theirs is the only residence in the laneway, its like their backyard.

Architect Brian Zulaikha and his partner, artist Janet Laurence, are also relatively land locked. Apart from a small outdoor terrace, their main garden forms part of the reserve, which Laurence looks after. Rather than include bedrooms that are rarely used, the house has only one bedroom. There is a built-in chaise directly under the stairs, which is used by guests. Theres also a small sunroom, adjacent to the kitchen, also used by guests, with a futon rolled out when needed.

Goads house includes a wide entrance/lobby with a series of doors that slowly reveal rooms.

Other homes featured in this book are highly flexible. Architect Dennis Rabinowitzs home, for example, is substantial in size. Although extending across six levels, the lower levels can be used independently, with their own back door accessed from the street to the rear. The home was also conceived as operating as a home office or as a gallery space down the track. Likewise, architect Sam Marshalls house was conceived as a family home. But a recent addition, which included three new rooms, could be either extra bedrooms or a home office in the future.