Contents

Page List

Guide

Cover

The

Museum

From its Origins to the 21st Century

Owen Hopkins

The Great Court of the British Museum, London

PREFACE

We take museums for granted. Even if they arent all free to get into, we assume museums will always be there; their doors never closed, their treasures always available to view. Yet for much of 2020 and into 2021, museums across the world were empty and silent, forced, like so much of society, to close as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic.

By any measure, this was a strange time to be writing a book about museums, and that moment has been indelibly imprinted upon it. The book reflects both the longing that I, and countless others, felt for the solace and community offered by contemplating a work of art, or wandering through museum galleries, but also the critical distance that this unprecedented period enforced.

As society begins to open up and, we hope, return to some semblance of normality, we are left grappling with what aspects of our lives will revert to the way they were before, and what may have changed for good. For museums, the immediate effects of the pandemic were dire. Shutting the doors to visitors not only cut off museums lifeblood, but also their main source of income. Mass furloughing and layoffs ensued. Some museums closed for good, others had to rely on lifelines offered by governments (frequently with strings attached). Longer term, the pandemic has accelerated several already existing trends, notably the decline of the blockbuster exhibition and the shift towards digital.

Although the pandemic has brought about a crisis of unprecedented proportions for museums, the last year has seen another event and movement whose impact has been even more profound and far reaching.

On 25 May 2020, a 46-year-old African American man named George Floyd was murdered in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA by city policer officer, Derek Chauvin. I cant breathe, the words uttered by Floyd as Chauvin knelt on his neck, became the cri de curfor mass rallies and protests in the US which spread across the western world, united under the banner of Black Lives Matter.

What had begun in 2013 as a protest against police brutality and racism became a broader movement against systemic racism across society, and the histories, institutions and structures that perpetuate it. As arbiters of what we value, what we remember, and also what we exclude, museums are undoubtedly complicit in this and Black Lives Matter has for many institutions prompted a concerted, if belated, period of learning and reflection.

The question is what happens next. It is sometimes said that museums hold up a mirror to society. But today it is not enough for museums to reflect the world as it is. By putting diversity, representation and racial equality at the forefront of their mission, they have the power as well as the duty to help bring about a more equal and inclusive future.

Void at eastern end of the Jewish Museum in Berlin, designed by Daniel Libeskind

Spiral staircase designed by Giuseppe Moro in Vatican Museum, Vatican City

INTRODUCTION: THE AGE OF MUSEUMS

In September 1968, the Belgian artist and poet, Marcel Broodthaers, announced the opening of the Muse dArt Moderne, Dpartement des Aigles, Section XIXme Sicle (Musuem of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, 19th-Century Section). Despite the traditional name, this was unlike any other museum. For a start, it would occupy Broodthaers house/studio on the rue de la Ppinire in Brussels. And secondly, he announced its opening before any of the objects it would contain yet existed. The works are in preparation, he wrote, their completion will determine the date at which we hope to make poetry and the plastic arts shine hand-in-hand.

These cryptic words became even more perplexing to visitors to Broodthaers museum when it opened on 27 September. The scene before them appeared, at first glance, as if they had arrived before the installation of artworks was actually finished. Empty picture crates, stencilled with the usual instructions handle with care and keep dry, were arranged casually around the room, with a ladder leaning against the wall, all as if the art handlers were still working. The only concession to visitors expecting from the title some exposition of nineteenth-century art were postcards of works by French painters of the era such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Jacques-Louis David, Gustave Courbet and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Meanwhile, slides of prints by the caricaturist J.J. Grandville were projected on the wall.

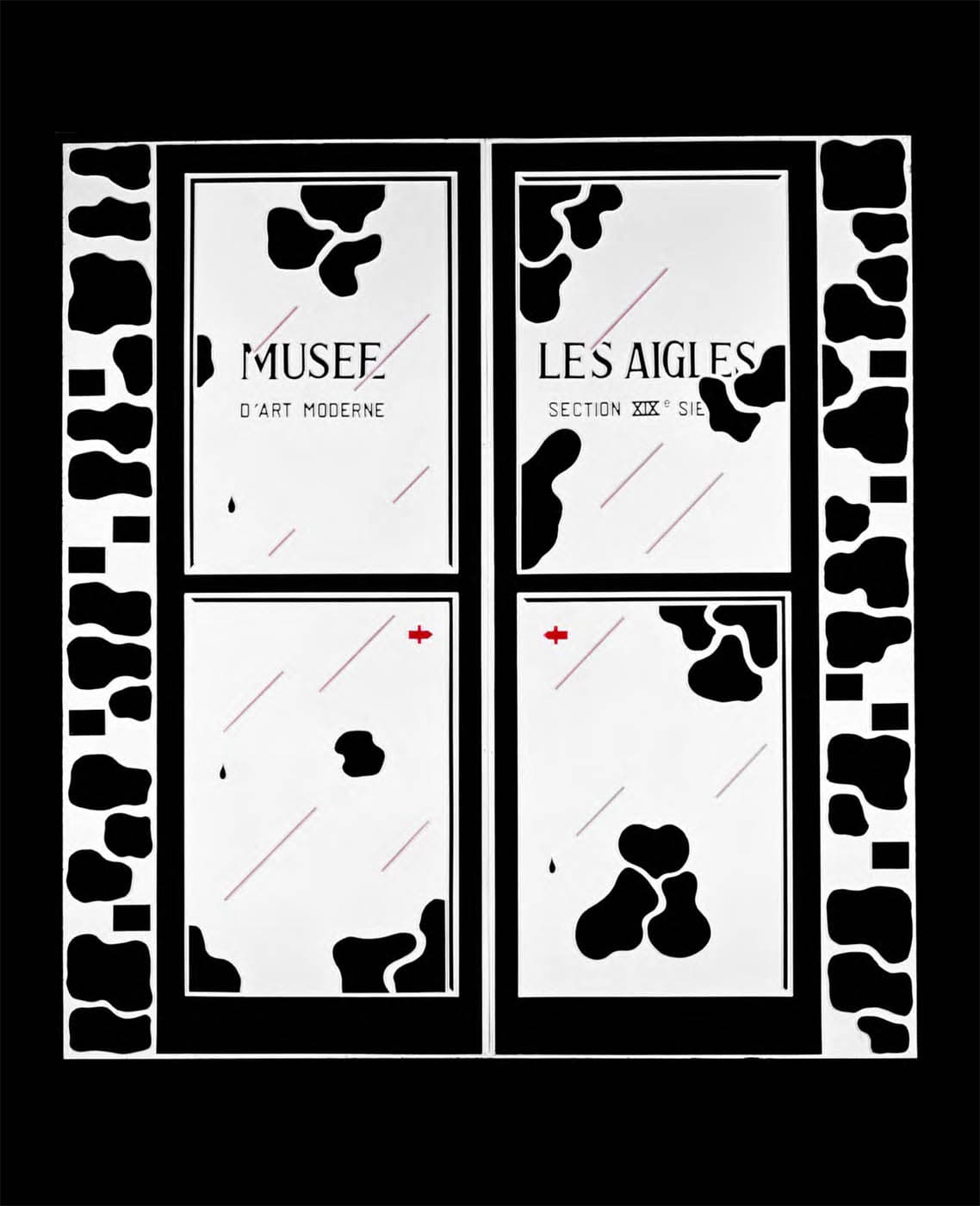

Left Les Portes du Muse dArt Moderne Les Aigles Section XIXme Sicle, 1969 by Marcel Broodthaers

Visitors who could see beyond the immediate strangeness of what Broodthaers had created would have also noticed some of the artists more subtle interventions. These included the careful addition of numbers to the doors of the rooms of his house so as to denote them as galleries, and the painting of the words muse/museum on the windows, announcing to the outside world that, for the duration of Broodthaers exhibition, this was no longer a house or studio, but had been transformed into a museum.

An open letter written by Broodthaers two months after the opening offered something by way of an explanation of the project, albeit a rather cryptic one. Particularly revealing was the way he described the opening as having been attended by leading representatives of the public and the military and that the speeches were on the subject of the relationship between institutional and poetic violence. A short note thanking the shipping company was accompanied by an inventory of the Dpartement: the crates, the postcards, the projection and devoted staff i.e. Broodthaers himself, as the self-styled director of the museum. Alongside the entry for the postcards was printed a single word: overvalued.

Broodthaers Muse dArt Moderne, Dpartement des Aigles is considered a seminal work in the development of installation art and, more specifically, of an art practice that is often described as institutional critique. Broodthaers installation of crates brought into the view the usually hidden aspects of museum operations, such as storage, transportation and installation. By doing so he revealed the way museums appear as unchanging and eternal as something of a fiction, and exalting rather than obscuring the support structures that allow this faade to be maintained. The art itself was reduced to the status of a postcard, a cheap everyday item, yet, at the same time, one that is indelibly associated with the increasingly commercialized experience of the museum. And perhaps most critically, by bringing the museum into his house/studio, he overturned the essential distinction between the studio as a place of production, and the museum as a place of reception, of the studio being where culture is made, and the museum where it is seen.