Contents

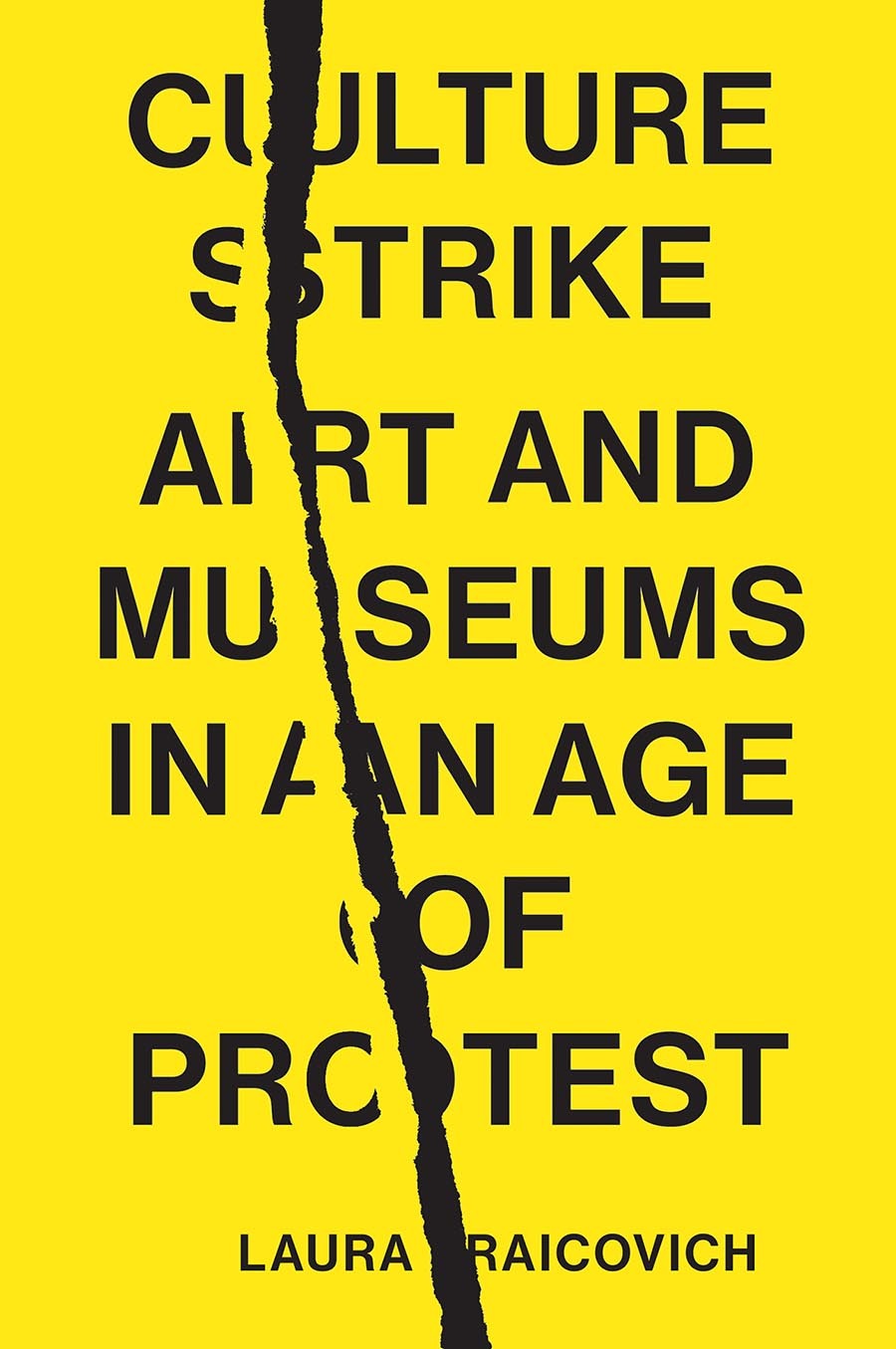

Culture Strike

Culture Strike

Art and Museums in an Age of Protest

Laura Raicovich

First published by Verso 2021

Laura Raicovich 2021

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-050-1

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-051-8 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-83976-052-5 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021930005

Typeset in Sabon by Biblichor Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY

for Giacomo Cender

Contents

We are living in an age of protest. Around the globe, radical movements, from prison and debt abolition to Extinction Rebellions climate activism, have penetrated mainstream discourse. Culture and art have, necessarily, also come under fire. While art has enormous potential to shift society, the institutions upon which it relies help hold systems of power in place. As much as I love museums and have dedicated my career to them, they are repositories of cultural hegemony, mirrors of societys ills, from enormous wealth gaps and other legacies of colonialism to the exclusion of historically marginalized groups. Museums and cultural spaces are part of the systems that protests hope to undo. I believe this undoing and redoing can not only make museums better for more people, but also map ways to make change in society at large.

My most recent experiences as the director of the Queens Museum, by turns exhilarating, challenging to my core, and heartbreaking, are central to this thinking. I led the museum for three extraordinary years through moments that proved to be highpoints of my professional life, and others that threatened to thwart my deeply held convictions of art and cultures vital engagement in societal change. A public museum, it is situated within a public park, in one of the most ethnically and culturally diverse geographies on the planet. In a city of immigrants, Queens, host to New York Citys two airports, is the place most newcomers arrive. Many stay in the string of neighborhoods along the 7 train, the boroughs spine, which transports a population that speaks over 138 different languages and dialects. Each subway stop opens doors into different cultures. And yet, we are all New Yorkers.

In awe of these realities, I took up my post at the Queens Museum in January 2015. Just eighteen months later, the election of Donald Trump would dramatically shift the landscape in which I worked. While the museum remained on an upward trajectory of increased attention, support, and visibility, the results of the election deeply impacted the staff and our publics and collaborators surrounding the Museum. Over a decade before I arrived at the Queens Museum, community organizers had been hired in a brilliant move to connect with nearby immigrant communities. Led initially by Jaishri Abichandani, and then by Prerana Reddy, this organizing effort created a new model for how museums could engage with their publics. The goal was not just to bring people to the museum, but rather to leverage its resources to surface and enact desires of these communities via cultural organizing.

In the aftermath of the election on November 8, 2016, the Trump administrations policies and rhetoric unleashed a Pandoras box of hate, and one of its primary targets was immigrants. At this museum these new conditions were no mere abstraction, but an all-too-harsh reality. Five percent of the Queens Museums staff received Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) protections, President Obamas executive order that provided legal status to many people brought to the United States without documents as children. This group heard Donald Trumps promises to repeal DACA, without which they would risk losing temporary relief from legal uncertainty, or even face deportation to countries they had never visited.

Further, in the weeks following the election, many of the people with whom the museums staff had collaborated for more than a decade and a halfthrough its free family programs; the New New Yorkers art classes taught in over a dozen languages; gatherings and classes at Immigrant Movement Whether or not the participants in these programs possessed documentation, there was worry of being caught up in a raid or being in the wrong place at the wrong time. I started getting Facebook alerts from various local groups spreading news of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) being at one or another subway stop, or heading to a particular neighborhood. Some even claimed that the alerts themselves were fake, sent out on social media to stir further anxiety and fear. City council members planned special sessions to reassure their constituents, and New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio convened a town hall in Corona with thencouncil member Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, along with a cadre of city agency heads and local uniformed police, to reassure immigrants that we were all New Yorkers no matter immigration status, and that local police forces and the educational system should be seen as allies.

In this climate, at the museum, we started holding weekly all-staff meetings. We contacted immigrant rights groups to be sure to stay updated on any changes in policy (whether local or federal) and shared this information with our networks; we coordinated with city agencies to be sure our staff and publics could access important information about their rights; we assembled a list of the museums resources that could be lent to local groups; and we decided to join the art strike called for Inauguration Day.

On January 20, 2017, while the Queens Museum was closed to regular operations, the staff created a program that invited the public to work with a printmaking collective on creating posters, buttons, and other ephemera for the coming protests. Over 300 people gathered in the atrium that day. I was deeply moved by this gathering of retired school teachers, artists, students, and local moms and grandmas. Throughout the day several in attendance thanked us for creating a space to gather on a day they felt so vulnerable. On that rainy day, it never would have crossed my mind that just over a year later I would resign my post.

What happened over the following twelve months would prove immensely complex. Several trustees did not like the fact that we were joining the Inauguration Day strike. Their position was that we should continue to do the work we had always done, but to do it quietly. At least one trustee expressed a fear of retribution from Trump via punitive tax audits of board members. From my perspective, not only had the political environment created a predicament in managing a staff with a significant number of increasingly precarious immigrants; I also felt strongly that we needed to be forthright and direct in our support for the communities with whom we had built a great deal over the years. Trust was at issue.

The staff and I drafted a restatement of values, which we felt would be an important buttress of our work. This took the form of a letter from the director that we posted to the museums website. I presented the values statement at the next board meeting, where it was unanimously approved. The statement, since removed, included the following: