ALSO BY CHARLES MOLESWORTH

POETRY

Common Elegies

Words to That Effect

CRITICISM

The Fierce Embrace: A Study of Contemporary American Poetry

The Ironist Saved from Drowning: The Fiction of Donald Barthelme

Gary Snyders Vision: Poetry and the Real Work

BIOGRAPHY

Marianne Moore: A Literary Life

Alain Locke: The Biography of a Philosopher

(co-authored with Leonard Harris)

And Bid Him Sing: A Biography of Counte Cullen

EDITED COLLECTION

The Heath Anthology of American Literature, co-editor, Modern Period

The Works of Alain Locke

THE CAPITALIST AND THE CRITIC

J. P. Morgan, Roger Fry, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art

CHARLES MOLESWORTH

University of Texas Press

Austin

Copyright 2016 by the University of Texas Press

All rights reserved

First edition, 2016

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to:

Permissions

University of Texas Press

P.O. Box 7819

Austin, TX 78713-7819

http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Molesworth, Charles, 1941 author.

The capitalist and the critic : J. P. Morgan, Roger Fry, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art / Charles Molesworth. First edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4773-0840-0 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-4773-0841-7 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-1-4773-0842-4 (non-library e-book)

1. Morgan, J. Pierpont (John Pierpont), 18371913. 2. Fry, Roger, 18661934. 3. Capitalists and financiersUnited States. 4. Art patronsUnited States. 5. ArtCollectors and collecting. 6. Art criticsEngland. 7. Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) I. Title.

HG2463.M6M65 2016

708.147'1dc23

2015016164

doi:10.7560/308400

This book is dedicated to C. H. M.

Love is dead in us

if we forget

the virtues of an amulet

and quick surprise.

ROBERT CREELEY

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

THOUGH I HAVE WRITTEN THREE PREVIOUS books that relied on the kindness of archivists, I remain thoroughly grateful for their skill and generosity. Several curators, archivists, and institutions were of persisting help in my writing this book.

James Moske, managing archivist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, assisted me with the correspondence by and about Roger Frys period of employment at the museum. He also went the extra mile in helping me obtain photographs and images related to that period. The curatorial staff at the Morgan Library and Museum made items available with a sense of welcome ease.

Robbi Siegel of Art Resources displayed equal parts helpfulness and patience in regard to my search for images. Photographs and material related to Roger Fry were graciously sent to me by Patricia McGuire, archivist at Kings College, Cambridge. Both Chris Sutherns, at Tate Images, and Alice Purkiss, Tates Library Executive, helped in selecting the photograph of Fry and his wife, Helen. Jennifer Bahus, of the North Carolina Museum, located the photograph of William Valentiner, taken by Ben Williams in 1956. Susan K. Anderson, the Martha Hamilton Morris Archivist at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, made the pen-and-ink portrait of John G. Johnson available for my use.

The staff of the Thomas J. Watson Library at the Metropolitan Museum Library made their holdings, along with their sophisticated equipment, readily usable. Lyndsi Barnes and Joshua McKeon of the Berg Collection at the New York Public Library were helpful and cordial, allowing me to study Clive Bells rare memoir.

The Apollo article on Horne and Fry was expeditiously sent to me by Imelda Barnard. Martha Hackley, of the Frick Collection, generously sent me a copy of Colin Baileys article on Fry, Frick, and the Polish Rider.

The stanza from Robert Creeley is an excerpt from The Warning from The Collected Poems of Robert Creeley: 19451975. Copyright 1962 by Robert Creeley. Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc., on behalf of the Estate of Robert Creeley.

Susan Dackerman shared with me a book on Bernard Berenson just as I needed it, and her discussion with me about the concept and practice of connoisseurship proved clarifying.

Fred Kaplan stood out as the most reliable person to read early drafts and to reiterate a trust in the project not always fully available to the author.

Norman MacAfees keen-eyed copyediting prevented dozens of infelicities from persisting, though all that remain are due to me alone.

Sarah Rosen, editorial assistant at University of Texas Press, remained steadfastly corrective as I dallied over and confused the acquisition and arrangements of the images in this book; her help is greatly appreciated.

My editor at the press, Robert Devens, never allowed my anxiety and doubt to reduce his commitment to moving forward. And so we did.

INTRODUCTION

Two Differing Portraits

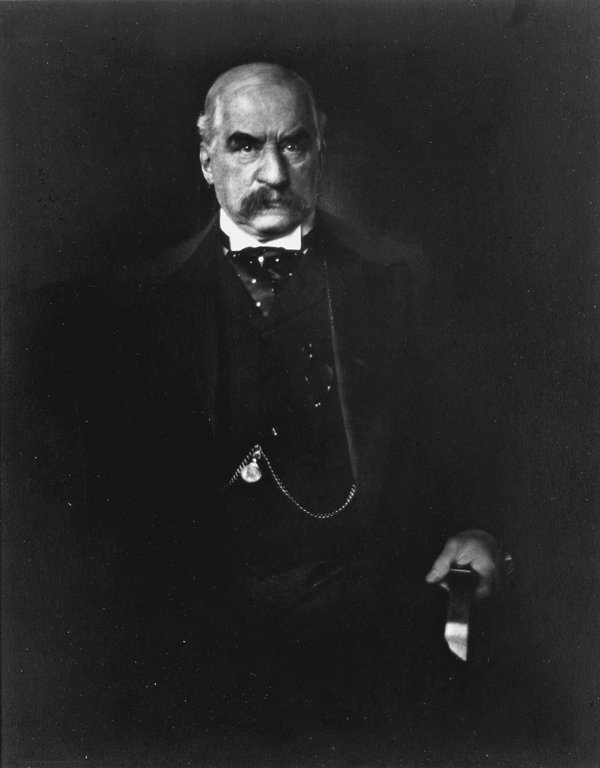

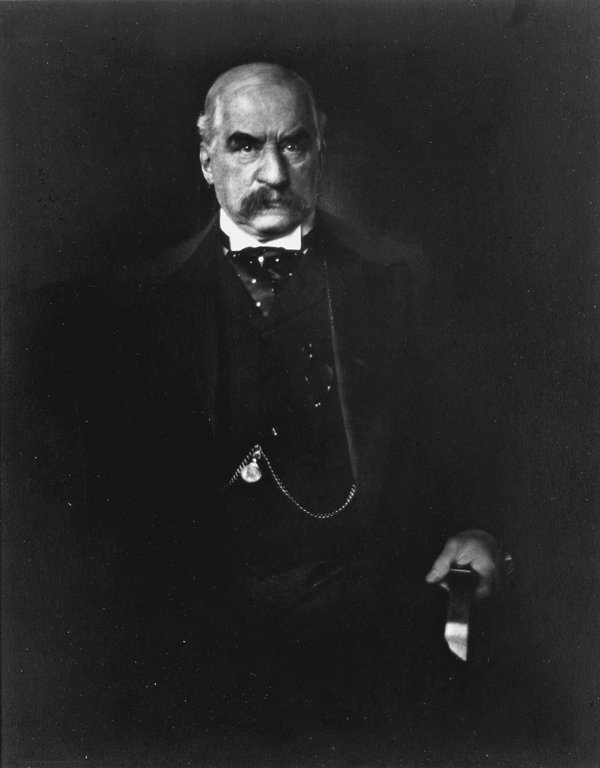

ONE WAY TO ENGAGE WITH J. PIERPONT MORGAN and Roger Fry is to examine their respective portraits. The most famous one of Morgan, the photograph by Edward Steichen, continues to circulate widely. Much of what we know of the man in the portrait rests on rumor and is concretized by myth. The story goes that Steichen was able to capture Morgans fabled sternnessmanifest in the glare of his dark eyes, once compared to the force of an oncoming locomotiveby a simple device. Steichen, after Morgan had laid aside his cigar and taken his seat, asked him to adjust his pose. The imperious sitter swiftly conveyed the resulting annoyance. His expression had sharpened and his body posture became tense, Steichen later recalled. I saw that a dynamic self-assertion had taken place. Steichen quickly took a second picture, and this is the one most often seen and discussed. The resulting grimace of disapproval summarized Morgans attitudes toward most things, and most people. Indeed massive disapproval must have been hidden behind that glaring figure; it was generally assumed that he felt time was being wasted on photography, time better spent on calculating the value of investments or interest rates or buying works of art.

The predatory nature of finance capitalism radiates from the reflection of the left-hand armrest of Morgans chair. Many have delighted to see in it a metaphoric knife blade; once offered, the association is hard to dispel. Again, how much of Steichens final image arose from luck and spontaneity and how much from pure artistic insight, we can never certainly know. The year of the photograph was 1903; Morgans Library was under construction, about to become one of the most famous private residences in the country (and eventually one of its finest cultural institutions). Morgan looks placed, situated. But at the same time the slight tilt to the right of his upper torso suggests a readiness to rise up and strike. The dominant sense intimates someone being intruded upon, even as he realizes he must pause and pose, if only for a brief menacing moment. We can be forgiven if the image of the dragon-like guardian of wealth comes unshakably to mind. About the wealth itself, there is no room allowed for fancy. Its extent was quite real, amounting a decade later to about $60 million when Morgan finally forever left his position as the wealthiest collector of art in America, and its most transformative banker. The myths appear plausible, as myths must.

Next page