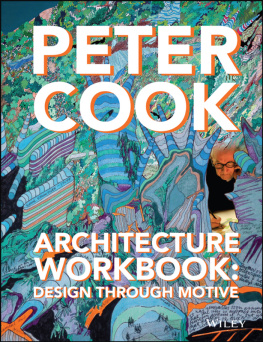

Drawing

This edition first published 2014

Copyright 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

First edition published 2008 by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com .

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com . For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com .

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: while the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

ISBN 978-1-118-70064-8 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-118-70059-4 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-70061-7 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-70062-4 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-82754-3 (ebk)

Executive Commissioning Editor: Helen Castle

Project Editor: Miriam Murphy

Assistant Editor: Calver Lezama

Dedication

TO YAEL AND ALEXANDER who keep me chirpy

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank Helen Castle, Executive Commissioning Editor, for her wise and steady advice, Caroline Ellerby, freelance editor, for her resource and tolerance over the long period during which this book has been folded in and out of my various activities. Miriam Murphy, Project Editor, for her deftness and understanding and Karen Willcox, freelance designer, for her spirited designing.

Introduction

Perhaps the ideal way in which an architect can approach the act of drawing is to be unaware that he is actually doing it at all.

Is it not a spontaneous means of summarising immediate intention? A form of jotting-down. Of course, other antennae of the brain are less encumbered. Shouting, murmuring, kicking or the wandering of the mind are less impeded by the necessary use of an implement, such as a pencil. The many effects on our consciousness of such implements has led to ceaseless pondering, whether it involves the impact of a lead pencil or the use of a particular computer program. Here lie so many of the debates about drawings themselves especially in a civilisation that is obsessed by the process.

Another issue that we have to get out of the way is the question as to whether architects drawings owe more to the demands of architecture or to an artistic inheritance where the particularisation of a building matters little. Into this come the issues of consciousness, state of mind and motive.

We know that the professional writer or journalist evolves towards habits of description and the ordering of information that parallel a written piece: the pre-edit, the trained mind and the articulation of key observations. We readily recognise and accept such symptoms.

So how do we deal with the undoubtable parallels in architecture? These easily cross beyond the thresholds of technique, preoccupation or style so that the priorities of an ideal emerge to be described in drawn lines that may enjoy those priorities.

Chapter 1

Drawing and Motive

Much of the most memorable or most definitive architecture comes forth at a moment when a set of ideas exists as a form of attack: a retort to another set of ideas. The pressure of rhetoric or drive needing to find an outlet, needing to shout loudly, to insist, awaken, reveal. The action will vary according to the temperament of the author and the means may well be highly conscious of the means used by the imagined adversary, whether this is an architect of an opposite persuasion or a sluggish and indifferent public. A parody of drawn mannerisms, or deliberately chosen cool in response to hot, or sparse in response to complex, closely paralleling the architecture itself or its cultural background. Thus the extraordinary clarity, fierceness and buildable rhetoric of the work that came out of the immediate post-Revolutionary Russia attacked on all fronts through composition, graphics, colour, film, music, material and, of course, the power of the accompanying verbal rhetoric. As such, it can be seen as a coherent piece.

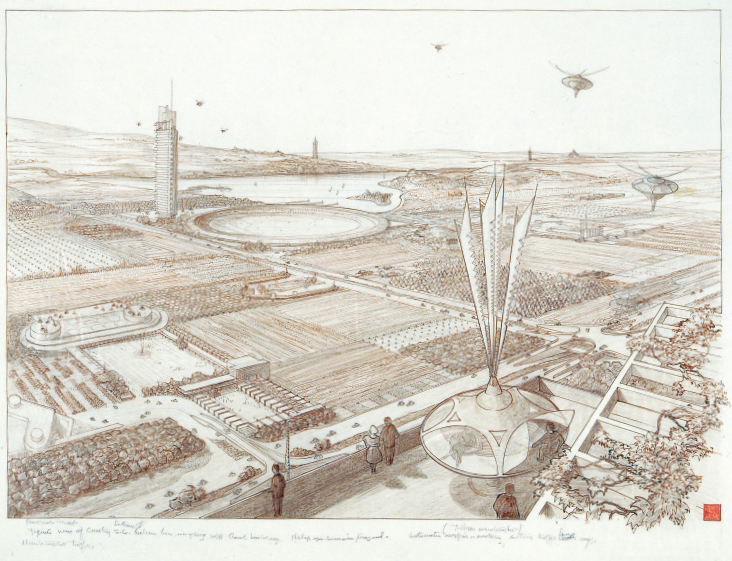

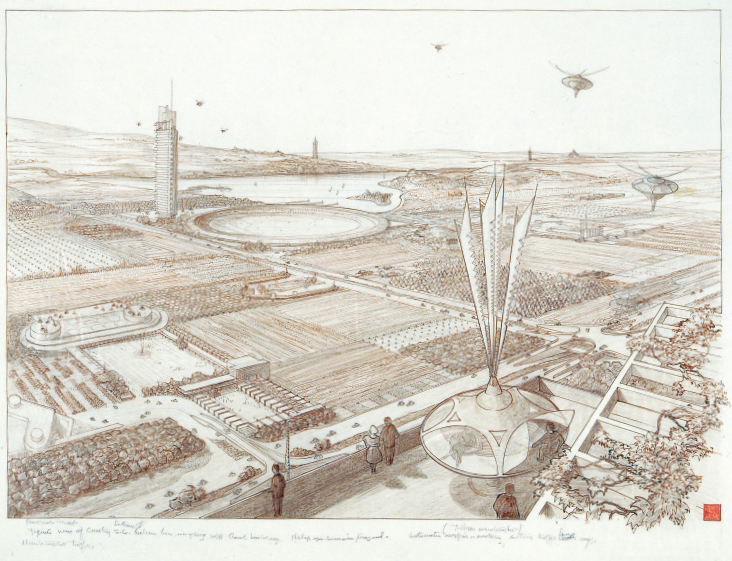

By contrast, one only has to glance at the kinds of drawings that accompanied Frank Lloyd Wrights Broadacre City (193258) and the subsequent Living City (1958), with their implications of endless Midwestern plains and soft, crafted materials and gruffly polite Midwestern conversation and values. They sought a natural expression of this through the medium of the deftly stroked coloured pencil: itself a fairly direct product of the soil.

Frank Lloyd Wright, Living City, 1958. Aerial view: pencil and sepia on tracing paper, 89.5 107.3 cm. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, Scottsdale, Arizona.

Delving into crazed territory, we realise that human will is an extraordinary phenomenon. If the desire is strong enough, the attack will be made ideally with the same integrity as the two scenarios just described. But otherwise using whatever resources come to hand.

There may not always be any particular correlation between the significance of a powerful architectural drawing and its inherent artistic merit, if we regard that in the illustrative sense. Such a relation between the representative aspects of illustration and selectivity will return as a central paradox in ones discussion. This questions the tradition that if a child displayed a talent for drawing and a grasp of mathematics, he or she would make a good architect.

Finding the Appropriate Visual Register

The vexed issue of comprehension converting itself into reproduction will crop up throughout this survey, but for the moment one is relating only to the issue of motive. Herein lie thousands of moments of irritation and frustration on the part of (even) the motivated: when the concept or maybe the image of a project is sitting there inside ones brain, but the drawn version is but a poor thing. Inhibited by technique, inhibited by clumsiness or inhibited because the imagined notion has no real precedent in familiar imagery.