This edition first published 2016

2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate,

Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-ondemand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-on-demand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: while the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-118-96519-1 (hb)

ISBN 978-1-118-96520-7 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-96523-8 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-96538-2 (ebk)

Executive Commissioning Editor:

Helen Castle

Project Editor:

Miriam Murphy

Assistant Editor:

Calver Lezama

Cover design and page design by

Karen Willcox,

www.karenwillcox.com

Layouts by Artmedia Ltd.

Printed in Italy by Printer Trento Srl

Cover image Peter Cook

Page 2 image Peter Cook, Chunk City, Ink and colour pencil, 2015

To Yael and Alexander

That I should be so lucky!

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the indefatigable Caroline Ellerby, who seems never to need rest. Equally to Helen Castle who knows so well how to keep me on the case and to the point. To Gavin Robotham who is a daily example of clear directedness and joviality. To Christia Angelidou who kept the illustrations coming faster than sound. To all of those above who tolerated my natural disinclination to enjoy the pedantry necessary to complete a useful document!

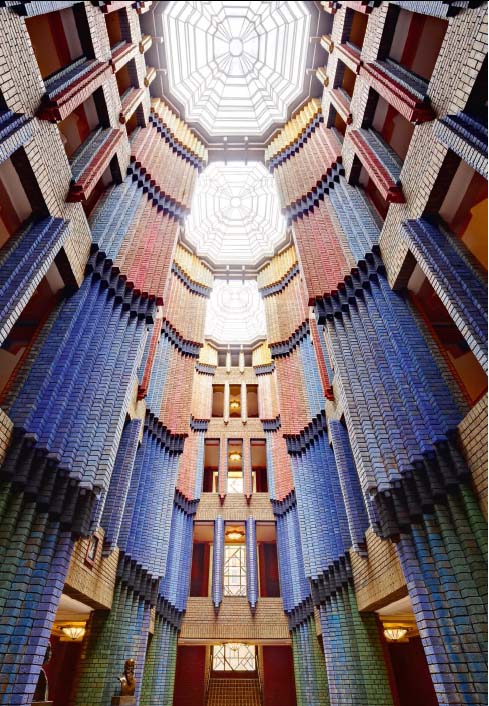

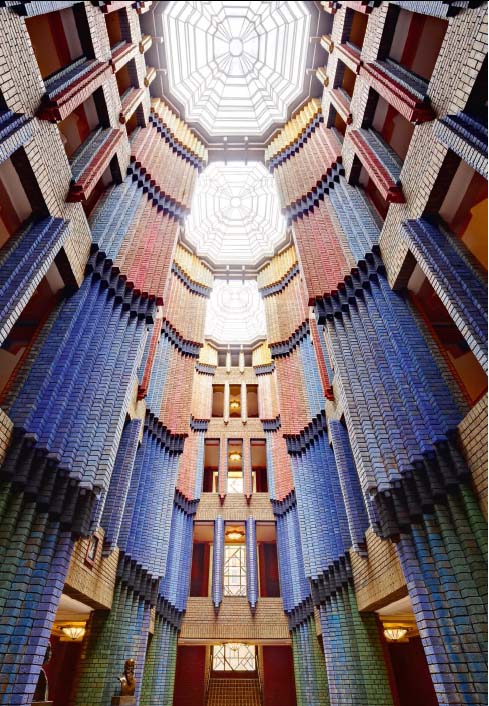

Peter Behrens, administration building, Hoechst Chemical Works, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1924: main hall.

An artist-turned-architect, Behrens created not only a dramatic almost Gothic space, but accentuated its sense of theatre by an assiduous use of stratified colour.

MOTIVE 1 ARCHITECTURE AS THEATRE

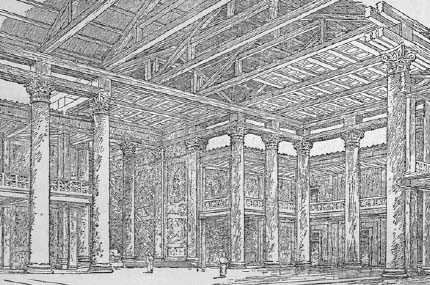

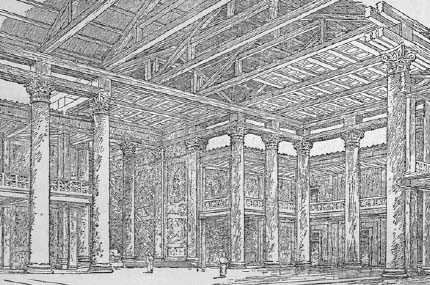

Vitruvius, basilica at Fano, Italy, 19 BC.

This is the only known built work of Vitruvius, effectively the first architectural theorist. If the visualisation is to be believed, it suggests that already by this time classical mannerisms had already established themselves.

Thinking about architecture, I have rarely felt the need to detach myself from the circumstances around me and certainly not by recourse to any system of abstraction. For this reason, most of the work discussed in this book is influenced by the episodic nature of events, by the coincidental, the referential, and is unashamedly biased. It seeks no truths but it enjoys two parallel areas of speculation: the what if? and the how could? that can be underscored by many instances of now heres a funny thing.

Thus each chapter revolves around a motive acting as a catalyst or driver of the various enthusiasms or observations, clarifying the identity of those same what ifs? and how coulds?. In each case the motive is elaborated upon by a commentary that tries to observe the world around us and the ironies and layers of our acquired culture. This precedes the description of the work itself. Of course there are times when such observations do or do not have any direct reference to what follows: yet I would claim that they sit there all the time, an experiential or prejudicial underbelly without which the description would lose dimension.

I do have a core belief, which I introduce here as the first motive: that for me, architecture should be recognised as theatre, in the sense that architecture should have character. It should be able to respond to the inhabitant or viewer and prepare itself for their presence, spatially; in other words, it should have that magic quality of theatre, with all its emphasis on performance, spectacle and delight.

Bernard Tschumi, National Theatre and Opera House, Tokyo, 1986.

A competition project that demonstrates Tschumis often-demonstrated ability to create a very clear concept and strategy for a building; a figure that also recalls 20th-century musical scores.

Indulging in Delight

If the Ancient Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius came out in favour of firmness, commodity and delight as the key elements of architecture in his celebrated treatise De architectura (Ten Books on Architecture), we are by now, in the Western world, so statutorily bound into systems of checks and balances standards, codes and building inspections that non-firmness is unlikely. Yet commodity can be more: it is not just the common-sense placing of things, for these can also be placed wittily and thus lead directly to the experience of delight. It is only dull architects who are immediately happy if buildings just have everything in the right place and leave it at that. But delight. This is a contentious beast; it involves evaluation, sensitivity, and even that difficult issue: taste.

What delights one irritates another, but both are alerted: their world is for the moment extended, identified, stopped in its tracks. If buildings are the setting for experience, then we may ask: can they influence that experience? It could be argued that people who are totally self-obsessed, or under extreme pressure, or blind, or in an extreme hurry may not notice where they are. But for the rest, the combination of presence, atmosphere, procedure and context add up to something that architecture should be aware of.

Next page