Arts and Crafts

A rts and crafts are synonymous with life in Myanmar. Life, in turn, is so closely intertwined with Buddhism that Buddhist devotion determines, in large part, the production of Burmese artisans and greatly influences their designs. Buddhism had become an integral part of Burmese life at least by the mid-fifth century of the first millennium: from that time onward, objects were created which reflect not only the superb craftsmanship of the artisans but also their fervent Buddhist beliefs.

This craftsmanship is based on a legacy of untold generations. Spectacular discoveries in the Pyadalin Caves comprise rock paintings, stone implements and cord-impressed pottery created about 11,000 years ago. In a report (The Quaternary Stratigraphy and Palaeolithic-Neolithic Evidences from Central Burma, University of Rangoon, 1985) on the investigation of some 31 archaeological sites in Central Myanmar, Thaw Tint and Sein Tun describe the discovery of a profusion of antiquities. These range from articles belonging to the Neolithic Age proper, to what they designate as the "metal age", and the early historical period. It determined that many present-day towns and villages, including well-known historical sites, are still situated in the same locations as Neolithic habitational clusters, some of which were nearly the same size as the modern settlements.

The authors found evidence of bronze metallurgical processing in at least five Neolithic sites in Central Myanmar, with the most developed in the lower Chindwin region (Mokhtaw, Aungtaung and Kyaukka) and around the volcanic areas (Songon-Mt Popa). From these, bronze knives, spearheads, axes or adzes and copper matte pieces were collected. In almost all the bronze sites, iron metallurgy and implements were also in evidence. This suggests that while bronze may have been produced earlier, iron and bronze were also produced together in what appears to be the late Neolithic era. A bronze hook, along with iron rods and knives, dated to about 460 BC, was found at Taungthaman (a site in modern Amarapura). Other items included bone or stone needles and spindle whorls, attesting to the existence of weaving skills and garment production at Neolithic settlements.

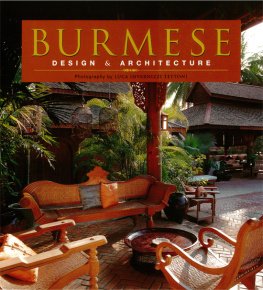

A typical example of the Burmese artisan's devotion to Buddhism, an antique manuscript cabinet embellished with a shwe-zawa (gold-leaf) design. At the centre is a kneeling deva, hands in a gesture of adoration holding lotuses in veneration of the Buddha; the whole is enriched by a wide convoluted lotus-leaf design. Courtesy of Patrick and Claudia Robert.

The hsun-ok, a Buddhist votive receptacle. The two here represent two aspects of Burmese art: one unadorned, yet noble, the other greatly embellished. From the Nunnery at Sagaing.

Creativity with exactness and patience is demanded of artisans decorating yun incised lacquerware. Here, at U Aung Nyunt's workshop in Bagan, they apply an englobe of yellow lacquer to fill the etched lines of a design; thereafter, the excess lacquer will be removed.

Dress and ornamentation, including jewellery, have always been important in Burmese culture. The presence of the court assured that materials wou ld be finely woven, with appropriately regal designs. The Manshu, the 9th-century Chinese chronicle, describes Pyu women of Central Myanmar as wearing a high coiffure adorned with gold, silver and real pearls. Bagan was so rich during the reign of King Kyanzittha (r 1084-1113) that, in his great inscription at the Shwezigon pagoda, he declared that even poor people would wear golden ornaments and handsome clothes. Mon ceramic plaques of the 15th century bear figures of Mara's daughters wearing beautifully decorated hta-meins (wraparound skirts). Konbaung kings of the late 18th and 19th centuries made sure that royalty was clad in lun-taya acheik silk, time-consuming to weave and extremely intricate of design, in pazun-zi (cloth of gold and silver lace) and in both imported and palace-woven velvets. The laity were responsible for weaving the monks' robes, kabalwe (cloth covers for Buddhist manuscripts) and sasigyo, used to bind the kabalwe.

Manuscripts constituted an artwork in themselves, as well as being the bearers of important Buddhist texts. The decoration of kammavaca, manuscripts dedicated to extracts of the Vinaya (Discipline), involves lacquer design, while accordion-pleated mulberry paper manuscripts known as parabaik, often bear paintings which at times are related to the art of the murals.

When and where the art of lacquer came to Myanmar is still a matter of intense debate. The generic name for lacquer is yun, but this term also describes incised lacquer objects with themes mainly related to the Jatakas, the stories of the 547 lives of the Buddha prior to his birth as Prince Siddattha, court scenes, and local legends and tales. Other lacquer decorative techniques include shwe-zawa (gold leaf), hman-zi shwe-cha (glass inlay) and thayo (relief-moulded).

Many of the themes employed in lacquerware are related to those of the murals, of which the greatest early body in Southeast Asia is in Bagan. These murals, undoubtedly based on an earlier tradition of paintings which are no longer extant, completely filled the walls and vaults of the temples. Over the following centuries, the basic themes of the Bagan murals-the Jatakas, Footprints of the Buddha, Life of the Buddha and the 28 Buddhas which have thus far appeared-remained, but styles of presentation changed.

It can be assumed that complementary wood carvings existed, but only a few from early Bagan remain; the others date to the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the pre-eminence of Burmese woodcarvers goes unquestioned, as attested by a vast array of decorative and narrative masterpieces. These vary from simple low relief, to the extremes of complex, three-dimensional specimens of high relief, to masterful carvings in the round. Entire monasteries and the Mandalay palace, tragically destroyed in World War II, testify to the outstanding skill of the Burmese woodworkers, whose competence, as is general in Myanmar, is wedded to and inspired by Buddhism.

Artisans examine the mould of a Buddha image which has been fired in a temporary kiln to melt the wax and to harden the clay for the reception of molten bronze.

A master sculpts in the specific details of the Buddha image's face after the second layer of malleable wax has been applied. After this, the image will be covered with two layers of clay, and prepared for casting.

Also related thematically to the murals of Bagan is a unique expression of the art of tapestry in the Burmese wall hangings known as kalaga ("Indian curtains"). These are distinctive for their sequinned and padded figures with sophisticated embroidery in stylized poses, illustrating the basic motifs of Buddhist art, and have become popular collector's items.

The temples of Bagan and Bago have long been known to be adorned with glazed plaques devoted largely to the Jatakas and portrayals of Mara's army. Only recently, however, have glazed ceramic wares-known to have been produced in Myanmar-been discovered. This discovery has opened a whole new field of study. Indeed, it has led to the realization on the part of art historians that there are still many unknowns about many of the arts and crafts in Myanmar.