Bibliography

Alfieri, B. M., Islamic Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Ahmedabad: Mapin, 2000.

Archaeological Survey of India, Archaeological Remains: Monuments and Museums, Pts 1 and 2, Delhi, 1996.

Arshi, P. S, Sikh Architecture in the Punjab, New Delhi: Intellectual Publishing, 1986.

Aryan, K. C., Basis of Decorative Element in Indian Art, New Delhi: Rekha, 1988.

Bannerjee, G. N., Hellenism in Ancient India, Calcutta: Probstian, 1920.

Basham, A. L., The Wonder That Was India , London: Sedgwick and Jackson, 1954.

Batley, C., The Design Development of Ancient Architecture, London: Academy Editions, 1973.

Begley, W. E. and Desai, Z. A., Taj Mahal: The Illumined Tomb, Massachusetts: The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1989.

Brown, P. , Indian Architecture, Vols 1 and 2, Bombay: Taraporewala, 1941 and 1956.

Bussagli, M., Oriental Architecture, New York: Abrams, 1973.

Davis, P., Splendours of the Raj, London: Penguin, 1987.

Deva, K., Temples of North India, New Delhi: National Book Trust, 1969.

Donaldson, T. E., Hindu Temple Art of Orissa, Vols 1-3, Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1987.

Doshi, S., The Impulse to Adorn, Bombay: Marg, 1982.

Grover, Satish, The Architecture of India, Buddhist and Hindu, 2nd edn, New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors , 2003.

, Islamic Architecture of India, 2nd edn, New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors, 2002.

Grunwadel, A., Buddhist Art in India, Varanasi: Bharatiya Publishing, 1974.

Harle, J. C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, New York: Viking Penguin, 1986.

Havell, E. V., The Ideals of Indian Art, London: John Murray, 1911.

, The Ancient and Mediaeval Architecture of India, New Delhi: S. Chand, 1972.

,Indian Architecture, New Delhi: S. Chand, 1913.

Herdeg, K., Formal Structure in Indian Architecture, New York: Rizzoli, 1990.

Hoag, J . , Islamic Architecture, New York: Abrams, 1977.

Huntington, S. L. and Huntington, J. C., The Art of Ancient India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, New York: Weatherhill, 1993.

Iman, Abu, Sir Alexander Cunningham and the Beginning of Indian Archaeology, Dhaka: Asiatic Society of Pakistan, 1966.

Irving, R. G., Indian Summer, New Haven: Yale University, 1982.

Koch, Ebba, Mughal Architecture, New Delhi: TBI, 1991.

Kramrisch, Stella, The Art of India, London: Phaidon, 1954.

, Hindu Temples, Vols 1 and 2, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1946.

,Indian Sculpture, Calcutta: YMCA, 1933. Meister, Michael W. and Dhaky, M. A. (eds.), Encyclopedia of Indian Temple Architecture, Vols 1-4, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1983-91.

Metcalf, T. R. , An Imperial Vision, London: Faber, 1968.

Michell, George, Architecture of the Islamic World, London: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

,Brick Temples of Bengal, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

, Hindu Art and Architecture, London: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Morris, J., Stones of Empire, London: Penguin, 1984.

Mukerji A. , Ritual Art of India, London: Thames and Hudson, 1985.

Pal, P., . Jain Art from India, London: Thames and Hudson, 1995.

Pereira, J., Elements of Indian Architecture, New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas, 1987.

,Islamic Sacred Architecture, New Delhi: Books and Books, 1994.

Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India, London: Penguin, 1953.

Sarkar, H., Early Buddhist Architecture in India , New Delhi: Munshirarn Manoharlal, 1966.

Sivaramamurthy, C., The Art of India, New York: Abrams, 1977.

, Early Indian Architecture, Vols 1 and 2, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1991.

,Panorama of fain Art, New Delhi: TOI, 1983.

Soundara Rajan, K. V., Indian Temple Styles, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1972.

Speaking Stones: World Cultural Heritage Sites in India, New Delhi: Eicher Goodearth, 2001.

Tadgell, Christopher, The History of Indian Architecture: From the Dawn of Civilization to the End of the RaJ, London: Architecture, Design, and Technology Press, 1990.

Tillotson, G. H. R., Paradigms of Indian Architecture: Space and Time in Representation and Design, SOAS Collected Papers on South Asia, 13, London: Curzon Press, 1997.

, Rajput Palaces, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

Varma, P. , Mansions at Dusk, New Delhi: Spantech, 1992.

Volwahsen, A. and Stierlin, Henri (eds.), Architecture of the World: India, Cologne: Benedikt Taschen, 1993.

, Architecture of the World: Islamic India, Cologne: Benedikt Taschen, 1993.

Zimmer, Heinrich R., The Art of Indian Asia, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955.

,Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

Residential Spaces

Traditional Indian households lived by the joint family system whereby the many occupants and complex interpersonal relationships necessitated clearly demarcated spaces. Public and private areas were separate, and women kept protected from the public gaze. The internal courtyard was the center, restricted to family members, with rooms opening out on either side, ensuring privacy to their inhabitants.

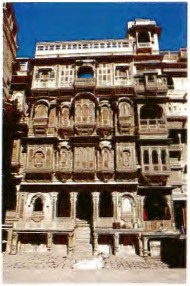

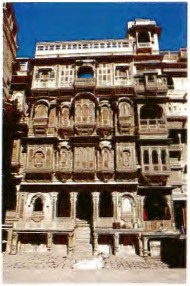

The stone faades of havelis in Rajasthan. Ornate jharokhas (balconies) with wooden shuttered openings project out onto the street. They are shaded by arched chhajjas (eaves).

North India: The Haveli

The haveli or mansion was the house of the rich, owned by either the nobility or by rich traders who attempted to imitate the lifestyle of royalty. Often built on narrow streets, the outer walls of larger havelis rose 3-4 stories high, casting shadows on their neighbors. Interiors thus remained cool. The narrow streets also acted as wind funnels, further cooling the buildings.

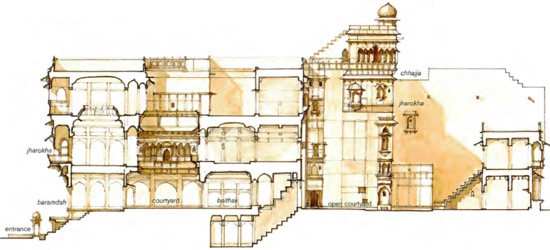

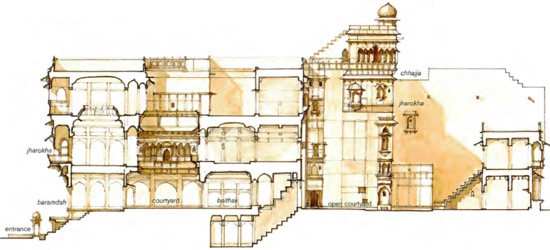

The haveli was built on a high plinth, with steps leading up to the entrance. The first room, facing the street, was the baithak or public area. It signified the transition between the public space outside the house and the private or personal space within. This was a totally male domain into which women rarely entered. The baithak opened out into another room, beyond which, completely shielded from the gaze of strangers, was the central courtyard.

A pillared and covered corridor called the baramdah or verandah ran around the courtyard on all levels, leading into various rooms that formed the living quarters. Rooms on the upper floors also had canopied balconies called jharokhas looking down into the street. Shielded by carved stone latticework screens (jaalis), they allowed the inhabitants to look out without being seen, and also served to break the force of hot winds, allowing the interiors to be airy. There was usually a teh khana or basement, which was the cool retreat of the house and also the place where valuables were stored. Security was, in fact, a major determinant in the plan. Doors had low lintels and high thresholds, probably to ensure that an unwelcome person could not enter easily. The staircases, too, were twisted and narrow, with uncomfortably high risers.

Section of a typical haveli showing the hierarchy of private and public spaces and connecting passageways.