Introduction

India is a word that invokes a host of clichs: a timeless civilization of living traditions, great spiritual wisdom and artistic riches; a subcontinent of astonishingly diverse yet harmonious regional, religious and linguistic differences; a crucible of cultural synthesis. Architecture is central to the supporting imagery, the forms and textures of iconic buildings such as the Taj Mahal dominating the phantasmagorical images of exotic splendour and difference that tourism, the media and popular culture readily propagate. For the urban middle classes and elites of modern India, no less than the desiring foreign tourist, these are some of the decidedly romantic idealizations of India that increasingly must be distinguished, if not salvaged, from the invading sameness of global urbanity.

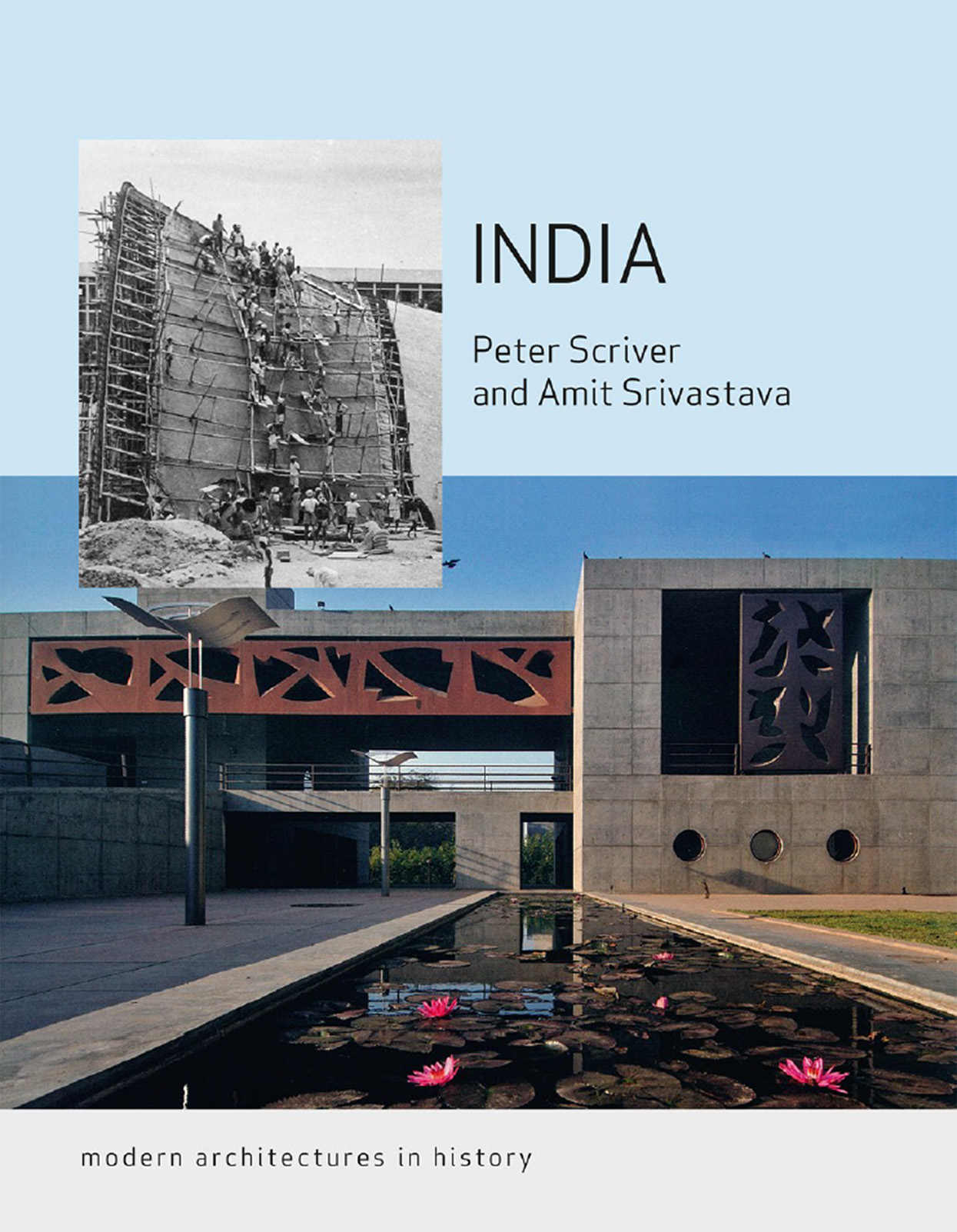

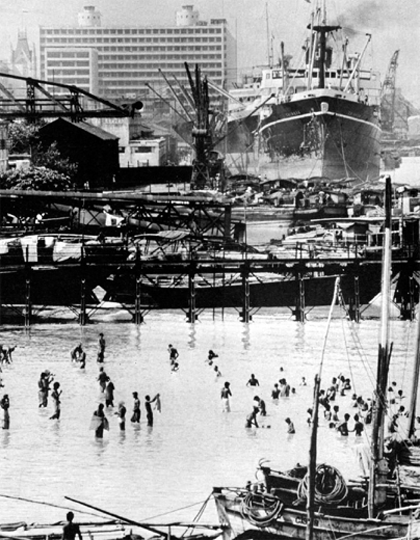

The idea of Modern India therefore invokes rather more equivocal clichs: a world of contrasts and contradictions, rich and poor, extravagance and destitution, space-age know-how but medieval means an incomplete project. It is construction sites in this case, more so than finished buildings, that furnish some of the most telling imagery. As the four-year-old daughter of one of the authors asked with innocent fascination upon arriving in Bombay (Mumbai) for the first time: Daddy, why are all the buildings falling down? Indistinguishable to her uninitiated eyes were the gangling new structures that clambered for presence in the cluttered skyline and the ramshackle bustees (slums) at their feet. They were still girdled in rough-hewn wooden scaffolding and ragged shrouds of hemp, and she could not discern the difference between the rising apartment towers and luxury condos intended for the upwardly mobile new middle classes and elites of metropolitan India, and the provisional accommodation that the low-paid migrant construction workers from the impoverished countryside had cobbled together from waste materials to shelter themselves during their seasonal employment in the big city.

It was a similar but almost wilfully naive sense of fascination with both the prospects and the paradoxes of Indias architectural engagement with modernity that began to be captured by architectural photographers in the 1950s as the newly independent, self-consciously modern India began to build. Particularly telling are some of the early construction Now free from the imposed tastes and paternalistic expertise of British colonial technocrats, however, it was more than a little paradoxical that the commission for the planning and design of this icon of change had ultimately been awarded to a non-Indian team of senior consultants dominated, famously, by the Swiss-French starchitect of the day, Le Corbusier, but still officially led by yet another Englishman, Maxwell Fry, in collaboration with his wife, Jane Drew. More paradoxical still was the gulf between symbol and reality from the point of view of technical development. Le Corbusiers designs for the monumental capitol complex at Chandigarh were some of the most audacious masterworks of modernism the world had yet witnessed. Yet here they were in these canonical photographs emerging virtually handmade, as the picturesque compositions typically emphasized, from the rude materials and sweat of a still largely pre-industrial society.

Hafeez Contractor, The Imperial residential condominium towers under construction in Mumbai in early 2008.

For members of Indias young architectural profession who first viewed such images in the pages of progressive international journals like the Architectural Review and its aspiring Indian counterparts, Marg and Design, among other local professional and trade magazines, if not through their own cameras on pilgrimages to the new city itself, the iconic building works at Chandigarh were an almost sacred site of encounter with the cutting edge of modern architecture, as well as the gaze of the international architectural community.

Through the lens of Chandigarh, by the mid-1950s architects and planners abroad had begun to watch modern India with increasing interest. For both the advocates of high modernism and its emerging critics, the conspicuous roles that progressive architecture, design and town planning were being called to play in Indias nation-building efforts were test cases for the global extension of the Modern Movement and its claims of universal validity and utility beyond simply an international style.

In Nehrus strategic vision for Indias modernization, Chandigarh was of enormous importance. It hits you on the head, and makes you think, he famously argued. You may squirm at the impact but it has made you think and imbibe new ideas, and one thing which India requires is being hit on the head so that it may think.

This book is an attempt at a longer critical history of this elusive notion of modernity in the changing architectural ideals and building cultures of modern India. While the growing body of literature on the Such a history is needed not only to cross-examine and interpret the wealth of architectural discourse and related historical material that remains, in many cases, only footnotes to the established narrative. It is also needed to provoke and hopefully deepen critical assessments of architectural developments in Indias recent past, and the debates that shaped them. Such a critical appreciation of previous modernities offers crucial historical perspective to address the huge new challenges and possibilities for the architectural and urban futures that the new India of the twenty-first century is already beginning to build as it aspires to play a leading role in the increasingly Asia-centric world of the global present.