Anthem Press

An imprint of Wimbledon Publishing Company

www.anthempress.com

This edition first published in UK and USA 2012 by

ANTHEM PRESS

75-76 Blackfriars Road, London SE1 8HA, UK

or PO Box 9779, London SW19 7ZG, UK

and

244 Madison Ave. #116, New York, NY 10016, USA

Copyright Lionel Knight 2012

The author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Knight, Lionel.

Britain in India, 18581947 / Lionel Knight.

p. cm. (Anthem perspectives in history)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-85728-517-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 0-85728-517-3

(pbk. : alk. paper)

1. IndiaHistoryBritish occupation, 17651947. I. Title.

DS475.K65 2012

954.035dc23

2012026715

ISBN-13: 978 0 85728 517 1 (Pbk)

ISBN-10: 0 85728 517 3 (Pbk)

This title is also available as an eBook.

This ebook was produced with http://pressbooks.com.

Anthem Perspectives in History

Anthem Perspectives in History

Titles in the Anthem Perspectives in History series combine a thematic overview with analyses of key areas, topics or personalities in history. The series is targeted at high-achieving pupils taking A-Level, International Baccalaureate and Advanced Placement examinations, first year undergraduates, and an intellectually curious audience.

Series Editors

Helen Pike Director of Studies at the Royal Grammar School,

Guildford, UK

Suzanne Mackenzie Teacher of History at St Pauls School,

London, UK

Other Titles in the Series

Disraeli and the Art of Victorian Politics

Ian St John

Gladstone and the Logic of Victorian Politics

Ian St John

King John: An Underrated King

Graham E. Seel

For AMB and KMB

Acknowledgements

I thank warmly the principal and fellows of St Hughs College, Oxford for a Schoolteacher Fellowship which enabled me to read in this field. Professor Roy Bridges and my editor, Helen Pike, were enormously helpful. Many thanks are also due to Ronojoy and Monojoy Bose, Melanie and Alastair Bridges, Janet Darby, Gary Griffin, Jonathan Keates, Michael Knight, Jing Liu, Andrew McBroom, Roger McKearney, Richard Macmillan, Michael Magarian, Hari Shah, the late Subrata Shome, Mary Short, Ronojit Sircar, David Ward and, above all, my wife.

Preface

British India is now a distant memory and, works of family piety and nostalgia apart, attention has naturally moved to Indian history. As a consequence, it is not easy to find a modern reliable account of the ninety years of Crown rule. This short book, written in the light of the historiographical revolution of the past generation, aims to meet this want.

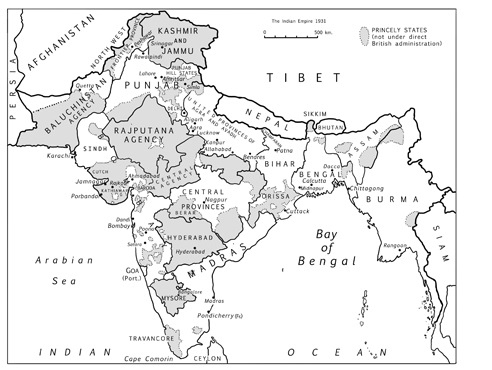

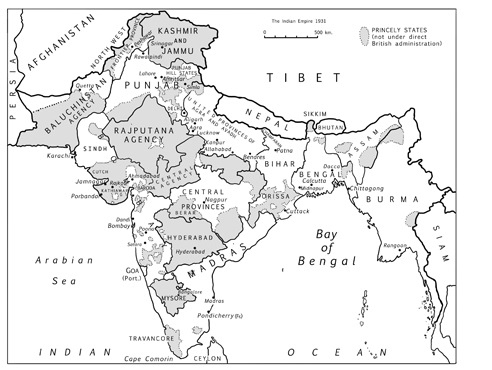

Map of India

Introduction

Britains Indian empire comprised the territories of contemporary India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Burma. The Straits Settlements of Penang, Malacca and Singapore were transferred in 1867 from British India to the Colonial Office which also controlled Ceylon/Sri Lanka. This immense tapering territory was about one thousand nine hundred miles both east to west and north to south, roughly the same size as Europe without Russia. Within this region there was great geographical diversity. In the north were the Himalayas, the worlds highest mountain range, from which flowed three of the earths great rivers, the Indus, Ganges and Brahmaputra. In peninsular India there was the high, dry tableland of the Deccan. In the west there were the 100,000 square miles of the Thar Desert. In the east at Cherrapunji a record 805 inches of rain was recorded in 1861.

This was an empire, not a unitary state with a single system of taxation and administration. New British provinces had been and would be added to the three presidency governments of Bengal, based in the capital city of Calcutta, and Madras and Bombay. What was called the Indian army was in fact the armies of these presidencies, with the commander-in-chief of the Bengal army exercising authority over the armies of Madras and Bombay. Elsewhere, the most important province was the Punjab, whose British officials thought of themselves as the most dynamic and innovative.

Scattered throughout the subcontinent were a large number of states under their Indian rulers. A semi-official work in the 1890s put the number by then at 688. Many were small and most were insignificant and grouped into agencies under British supervision. However, a dozen or so were large and important, uneasy survivors of the age of conquest and annexation. Hyderabad, ruled by the Nizam, had an area of 72,000 square miles and was the most heavily populated of these states, comprising nearly ten million people. Kashmir was almost the size of modern Britain but with a population of only 1.5 million. The government of Mysore, a state about the size of Belgium, was among the most sophisticated. The states had lost their external sovereignty, but retained varying degrees of domestic independence. They comprised two-fifths of India, but only one-fifth of the population.

The first census was published in 1872, giving a daunting total population of 241 million. Of these, 186 million were in British India, 54 million in the states, and three-quarters of a million in the Portuguese and French enclaves. There were also 121,000 Europeans, of whom 60,00070,000 were from British Army regiments, and 64,000 were Eurasians (mixed race). An official summarized the main divisions in the Indian population as 41 million Muslims, 16 million high-caste Hindus (Brahmans and Rajputs) 111 million mixed-population Hindus and 17.5 million aborigines; with other small minorities, Sikhs, Christians, Jains, Parsis and Jews. Though there were scores of minor languages, the major ones numbered about fifteen. Censuses were to become important instruments of government policy. They not only extracted information from the population, but also classified people in increasingly refined ways and forced them to choose identities. By 1901 a paper slip had been created for each person and manually sorted into pigeonholes for each different statistical tabulation needed. By then Indians were 80 per cent of all subjects of the British Empire. Much was made of their complex variety, which could be held to justify foreign rule as an external arbiter.