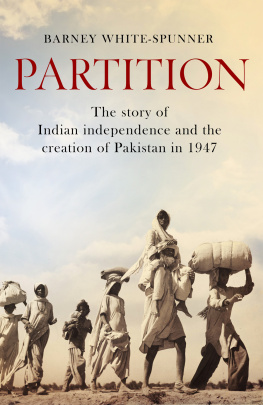

Dedicated to all those who lost their lives

in India and Pakistan in 1947

L IST OF M APS AND I LLUSTRATIONS

M APS

All maps ML Design

: India, 1947

: Punjab, August 1947

: Bengal, 1947

: Kashmir, 1947

I LLUSTRATIONS

Imperial War Museums (HU 87261).

: William Vandivert/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.

source unknown.

source unknown.

source unknown.

source unknown.

AP/REX/Shutterstock.

source unknown.

AP/REX/Shutterstock.

source unknown.

: Courtesy of Robert Beaumont.

AP/REX/Shutterstock.

Universal History Archive/UIG via Getty Images).

Margaret Bourke-White/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.

Margaret Bourke-White/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.

Max Desfor/AP/REX/Shutterstock.

N OTES ON THE T EXT

Place names. I have written place names as they were in 1947, so Bombay instead of Mumbai, Cawnpore instead of Kanpur, Ferozepore instead of Firozpur. I appreciate that there are some people who might be offended by this, as that in most cases these are the anglicised versions of the original Indian names. However, given that I am quoting contemporary accounts, it would not make sense to change them.

Language and terminology. Similarly I have throughout used the language and terminology common in 1947. Again this will seem anachronistic, even offensive, to some but it is logical given that I am trying to understand how people thought seventy years ago. The term classes, for example, to denote the various different racial and religious groups from which the British Indian Army was recruited, will grate with some readers, but it was the way in which those who divided that army thought.

Money. The currency across India in 1947 was the rupee, usually written as Rs, which is the convention I have followed in this book. The rupee was pegged to the pound sterling at the rate of Rs 13 to 1, so a rupee was worth a bit less than two shillings in old British money. A rupee was divided into 16 annas, so an anna was worth about one old-style British penny. The rupee coins had the King Emperors head on one side and a prowling tiger on the reverse. Pakistan continued to use Indian currency throughout 1947.

In 1947, rupees were often expressed, as they still are today in India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, as lakhs, which is 100,000, or as a crore, which is 10,000,000.

Style of address. Indian titles and honorifics are as confusing as British ones. I have tended to avoid them throughout so that Nehru is just Nehru, rather than Pandit Nehru, Pandit being a term of respect for a learned person; Patel plain Patel, rather than Sardar Patel, where Sardar means a chief or leader, and Mountbatten simply Mountbatten, rather than Rear Admiral Viscount Mountbatten of Burma. It is tempting to refer to V. P. Menon by his honorific Rao Bahadur, which means Most Honourable, and which was awarded formally as a title together with a badge, but instead, for the sake of consistency, I have referred to him throughout just as V. P. Menon and Krishna Menon, unsurprisingly, as Krishna Menon to avoid confusion.

Indian Words. There are, obviously, a lot of Indian words and expressions in the text. Anything in italics is explained in the glossary .

P REFACE

In 2008 I was the military commander of British and Coalition troops in Basrah and the three other provinces designated by the Coalition Authority in Baghdad as constituting the South Eastern Sector of Iraq. It was a time of some confusion. British troops had been withdrawn from Basrah city the previous summer. We were now based at Basrah airport, with insufficient numbers to do much more than protect the airport and unable to exercise much influence on the immediate area and very little on the outlying provinces. When we asked London for instructions we were told that our job was to stay put, ostensibly to help reopen the airport but in effect simply to be a continuing British presence to bolster an American effort that would be seen to be weakened morally, if not practically, should we withdraw. It was a strange strategy that did not convince many, least of all the Iraqis. British soldiers are at their best in such awkward situations but even their patience was tried by being restricted to guarding a perimeter while being subjected to periodic rocket attacks.

We had become a presence that supposedly conveyed international influence but in effect could be said to have damaged the United Kingdoms standing in the world. We had stayed on too long and with insufficient strength to do anything. We made this point to the then prime minister, Gordon Brown. I grew to respect his personal integrity and concern but his government struck us as having a weak team of strategic advisers. Ultimately, by developing a plan to deploy soldiers directly with the Iraqi Army, we were able to help them reoccupy Basrah and thus drive out the Iranian-backed militias that had been making life for Basrawis so miserable. But it was a difficult operation during which we lost the initiative. We then regained it and the British Army can look with some pride on the fact that Basrah is today the most peaceful part of Iraq, although that must remain a relative judgement given that the country as a whole is fragmenting.

But why had we stayed on so long in Basrah when it had become counter to our interests? Why hadnt we left when we had originally intended, that is, within eighteen months of the 2003 invasion? It was not as if we were overseeing the reconstruction of the Basrah economy or its infrastructure, which had been so badly damaged by a combination of Saddams general disinterest and occasional vindictiveness. Basrah in 2008 suffered from the same power shortages, lack of proper sewerage and mass unemployment as it had in 2003, despite all the effort that had been made to get London to take an interest in its development.

The British Armys experience in Iraq, and later in Afghanistan, also led many of us to think about how previous British armies would have coped and, in particular, how the whole mechanism of Imperialism had worked. We had been reared on the exploits of the British Indian Army, and their legacy was difficult to avoid in Iraq. We compared ourselves to them, generally unfavourably, and asked whether there were lessons to be learned from how they had organised and conducted themselves. Equally interesting was how the British administration had worked in the Empire; how had we managed to run huge economies like India while now we seemed unable to get the power stations working in Basrah?

Yet as we looked deeper we began to see cracks in the model of British India. The British Indian Army had undoubtedly been a most impressive if surprisingly delicate machine, yet the much-vaunted administration of the Raj did not seem to have achieved that much. The Indian peasant in 1932 had the same income and standard of living as when the Mughal Emperor Akbar died in 1605, just after the East India Company was founded in 1599. Was what we went through in Basrah actually just a repeat, albeit on a very small scale, of the same old British pattern of being unable to leave when it would have been in our and Indias best interests to do so? Staying on in Iraq achieved very little for our national interest but, more seriously, had our inability to leave India led to two of the worst losses of life in the twentieth century the Bengal famine of 194244 and Partition in 1947? And the great British Indian Army, designed specifically to keep internal order, and which had accomplished such an extraordinary victory over the Japanese in 1944, had then seemed powerless to act. Why?