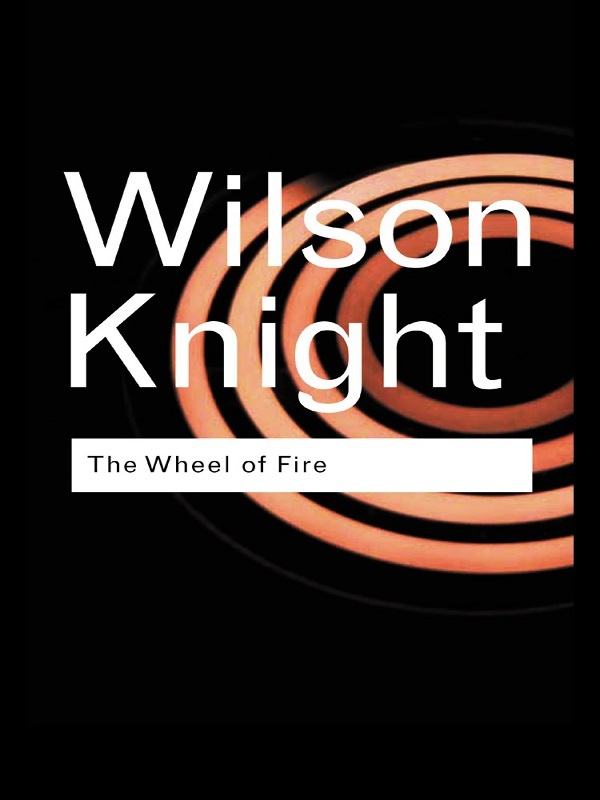

The Wheel of Fire

Professor Wilson Knight stands in a class by himself.... His work might be described as the analysis andinterpretation of genius, an arduous and heroic task forwhich he is peculiarly fitted by the possession not onlyof a penetrating intelligence but of imaginative powersof a very high order.

Professor V. de S. Pinto

For writing of this kind we cannot have too muchrespect.

The Times Literary Supplement

Wilson Knights essay inThe Wheel of Firegives theonly adequate account ofMeasure for MeasureI know.

F. R. Leavis, The Common Pursuit

G.

Wilson Knight

The Wheel of Fire

Interpretations of Shakespearian Tragedy

With an introduction by T. S. Eliot

First published 1930 by Oxford University Press

Fourth edition, including three new essays, published 1949

by Methuen & Co. Ltd

First published by Routledge 1989

First published in Routledge Classics 2001

by Routledge

11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005.

To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledges collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been applied for

ISBN 0-203-99605-4 Master e-book ISBN

ISBN 0-415-25561-9 (hbk)

ISBN 0-415-25395-0 (pbk)

You do me wrong to take me out o the grave:

Thou art a soul in bliss; but I am bound

Upon a wheel of fire, that mine own tears

Do scald like molten lead.

King Lear, iv. vii. 45

Two truths are told,

As happy prologues to the swelling act

Of the imperial theme.

Macbeth, i. iii. 127

PREFATORY NOTE

This re-issue of what wasexcept for my monograph Myth and Miracle (lately reprinted in The Crown of Life)my first book, contains the original text complete with only some insignificant, mainly typographical, alterations. My two original essays on Hamlet, Hamlets Melancholia and The Embassy of Death, are, for neatness, grouped as one. I have tidied up some mannerisms, but made no attempt at correction of matter, preferring to let the various essays stand as documents of their time with all their imperfections on their heads, while hoping that they may be found to have worn not too badly during the years since their first publication in 1930. Where there are additions, as with my additional notes and my three new essays, I have dated them. Of these essays, the first, on Tolstoys Attack, was originally published as an English Association pamphlet and is reprinted here by kind permission of the Association. The other two, Hamlet Reconsidered and Two Notes on the Text of Hamlet are quite new. I give line-references to the Oxford Shakespeare.

On looking back over the last two decades I feel that a short retrospective comment may help to clear up certain misunderstandings. My animadversions as to character analysis were never intended to limit the living human reality of Shakespeares people. They were, on the contrary, expected to loosen, to render flexible and even fluid, what

But here again a distinction is necessary. It has been objected that I write of Shakepeareas indeed did Coleridge, Hazlitt and Bradleyas a philosophic poet rather than a man of the stage. That is, in its way, true: and it is true that I would not regard the well-known commentaries of Harley Granville-Barker as properly within this central, more imaginative and metaphysical, tradition. Nevertheless, my own major interest has always been Shakespeare in the theatre; and to that my written work has been, in my own mind, subsidiary. But my experience as actor, producer and play-goer leaves me uncompromising in my assertion that the literary analysis of great drama in terms of theatrical technique accomplishes singularly little. Such technicalities should be confined to the theatre from which their terms are drawn. The proper thing to do about a plays dramatic quality is to produce it, to act in it, to attend performances; but the penetration of its deeper meanings is a different matter, and such a study, though the commentator should certainly be dramatically aware, and even wary, will not itself speak in theatrical terms. There is, of course, an all-important relation (which I discuss fully in my Principles of Shakespearian Production); and indeed the present standard of professional Shakespearian production appears to me inadequate precisely because these deeper meanings have not been exploited. The plays surface has been merely translated from book to stage, it has not been re-created from within; and that is why our productions remain inorganic.

So much, then, for what this new poetic interpretation is not. What, in short, can we say that it is?

A recent account by Mr. Lance L. Whyte of modern developments in physics, which appeared in The Listener of July 17th, 1947, can help us here. Mr. Whyte explains how the belief in rigid particles with predictable motions has been replaced by concepts of form, pattern and symmetry; and not by these as static categories only but rather by something which he calls the transformation of patterns. For particles put characters and we have a clear Shakespearian analogy. Even the dates, roughly, fit: From about 1870 to 1910 these particles were thought to hold the key to all the secrets of nature; but since then the conception has been found inadequate. Rigidly distinct and unchanging atoms have become patterns occupying certainly a measurable region of space but yet themselves, as patterns, dynamic, self transforming. The pattern itself moves; space and time coalesce; such is the mysterious design of nature. But, as too with Shakespeare, the old theories are not to be peremptorily dismissed. They are merely to be regarded as less than the utterly complete explanations they were once thought to be:

They have therefore to be re-interpreted as part of some more comprehensive approach. The answer may be that we must not think of patterns as if they were built out of particles, but that what we have called particles, may ultimately be better explained as components of patterns.

The argument against excessive character study could not be more concisely expressed.

Most important of all, however, is Mr. Whytes stress on the development and transformation of patterns. Though the causal analysis of detailed parts must be continued as before, we are henceforth to pay more attention to certain aspects of phenomena which have been neglected till now, like pattern-tendency and transformation. So the task before physics is to discover a new principle