CONTENTS

To Erroll McDonald

and

Beth Vesel

A NOTE ON THE TEXT

Unless otherwise noted, all references to Shakespeares plays are from the Norton Shakespeare Second Edition, eds. Stephen Greenblatt et al. (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008).

ILLUSTRATIONS

INTRODUCTION

T HE PREMISE OF THIS BOOK is simple and direct: Shakespeare makes modern culture and modern culture makes Shakespeare. I could perhaps put the second Shakespeare in quotation marks, so as to indicate that what I have in mind is our idea of Shakespeare and of what is Shakespearean. But in fact it will be my claim that Shakespeare and Shakespeare are perceptually and conceptually the same from the viewpoint of any modern observer.

Characters like Romeo, Hamlet, or Lady Macbeth have become cultural types, instantly recognizable when their names are invoked. As will become clear, the modern versions of these figures often differ significantly from their Shakespearean originals: a Romeo is a persistent romancer and philanderer rather than a lover faithful unto death, a Hamlet is an indecisive over-thinker, and a Lady Macbeth, in the public press, is an ambitious female politician who will stop at nothing to gain her own ends. But the very changes marked by these appropriations tell a revealing story about modern culture and modern life.

The idea that Shakespeare is modern is, of course, hardly a modern idea. Indeed, it is one of the fascinating effects of Shakespeares plays that they have almost always seemed to coincide with the times in which they are read, published, produced, and discussed. But the idea that Shakespeare writes usas if we were Tom Stoppards Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, constantly encountering our own prescripted identities, proclivities, beliefs, and behaviorsis, if taken seriously, both exciting and disconcerting.

I will suggest in what follows that Shakespeare has scripted many of the ideas that we think of as naturally our own and even as naturally true: ideas about human character, about individuality and selfhood, about government, about men and women, youth and age, about the qualities that make a strong leader. Such ideas are not necessarily first encountered today in the realm of literatureor even of drama and theater. Psychology, sociology, political theory, business, medicine, and law have all welcomed and recognized Shakespeare as the founder, authorizer, and forerunner of important categories and practices in their fields. Case studies based on Shakespearean characters and events form an important part of education and theory in leadership institutes and business schools as well as in the history of psychoanalysis. In this sense Shakespeare has made modern culture, and modern culture returns the favor.

The word Shakespearean today has taken on its own set of connotations, often quite distinct from any reference to Shakespeare or his plays. A cartoon by Bruce Eric Kaplan in The New Yorker shows a man and a woman walking down a city street, perhaps headed for a theater or a movie house. The caption reads, I dont mind if somethings Shakespearean, just as long as its not Shakespeare. Shakespearean is now an all-purpose adjective, meaning great, tragic, or resonant: its applied to events, people, and emotions, whether or not they have any real relevance to Shakespeare.

Journalists routinely describe the disgrace of a public leader as a downfall of Shakespearean proportions

Vivid personalities like Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, and William Randolph Hearst have likewise been described as figures of Shakespearean proportions or Shakespearean dimensions. Shakespearean in these contexts means something like ironic or astonishing or uncannily well plotted. Over time the adjectival form of the playwrights name has become an intensifier, indicating a degree of magnitude, a scale of effect.

Why should this be the case? And what does it say about the interrelationship between Shakespeare and modern culture?

SHAKESPEARE ONE GETS ACQUAINTED WITH without knowing how, says one earnest young man in a Jane Austen novel to another. It is a part of an Englishmans constitution, his companion is quick to concur. No doubt one is familiar with Shakespeare in a degree, he says, from ones earliest years. His celebrated passages are quoted by every body; they are in half the books we open and we all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions. This was modern culture, circa 1814. In the view of these disarmingly ordinary, not very bookish observers, Shakespeare was the author of their common language, the poet and playwright who inspired and shaped their thought.

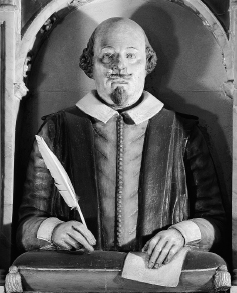

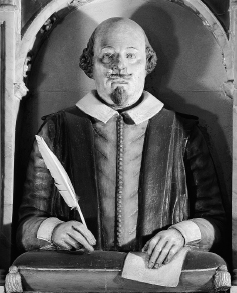

In 1828 Sir Walter Scott, already a celebrated novelist, visited the tomb of the mighty wizard, as he wrote. He had a plaster cast made of the Shakespeare portrait bust in Holy Trinity Church, and he designed a proper shrine for the Bard of Avon in the library of his home at Abbotsford, making sure that the bust was fitted with an altar worthy of himself. Scott noticed that the two of themScott and Shakespeareshared the same initials, W.S. He had their head sizes measured and compared by a German phrenologist. A bust of Scott was designed to resemble that of the other Bard, and after Scotts death the bust of his head replaced that of Shakespeare in the library. Admiration here became identificationor perhaps a kind of rivalry.

Gerard Johnson, William Shakespeares Funerary Monument, Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon

Shakespeares modernity would also be proclaimed in nineteenth-century America. In 1850 Ralph Waldo Emerson announced that, after centuries in which Shakespeare had been inadequately understood, the time was finally right for him: It was not possible to write the history of Shakespeare till now, Emerson wrote. The word now in his argument becomes the marker of that shifting category of the modern, and it is repeated for emphasis a few lines later. Now, literature, philosophy, and thought, are Shakespearized. His mind is the horizon beyond which, at present, we do not see. Our ears are educated to music by his rhythm. We live today in a new now, a century and a half removed from Emersons, but this sentimenthe wrote the text of modern lifeseems as accurate as it did then.

Noras we have already notedis this view the special province of literary authors. The frequency with which practitioners and theorists of many of the new modern sciences and social sciencesanthropology, psychology, sociologyhave turned to Shakespeare for inspiration is striking, but not surprising. Ernest Jones, Freuds friend and biographer, the first English-language practitioner of psychoanalysis, declared straightforwardly (in an essay he began in 1910, revised in 1923, and expanded in the 1940s) that Shakespeare was the first modern. Why? Because he understood so well the issues of psychology. The essential difference between prehistoric and civilized man, Jones argued, was that the difficulties with which the former had to contend came from without, while those with which the latter have to contend really come from within,

Next page