Shakespeare William - Forensic Shakespeare

Here you can read online Shakespeare William - Forensic Shakespeare full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Great Britain;Oxford;UK, year: 2018;2014, publisher: Oxford University Press, Incorporated, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

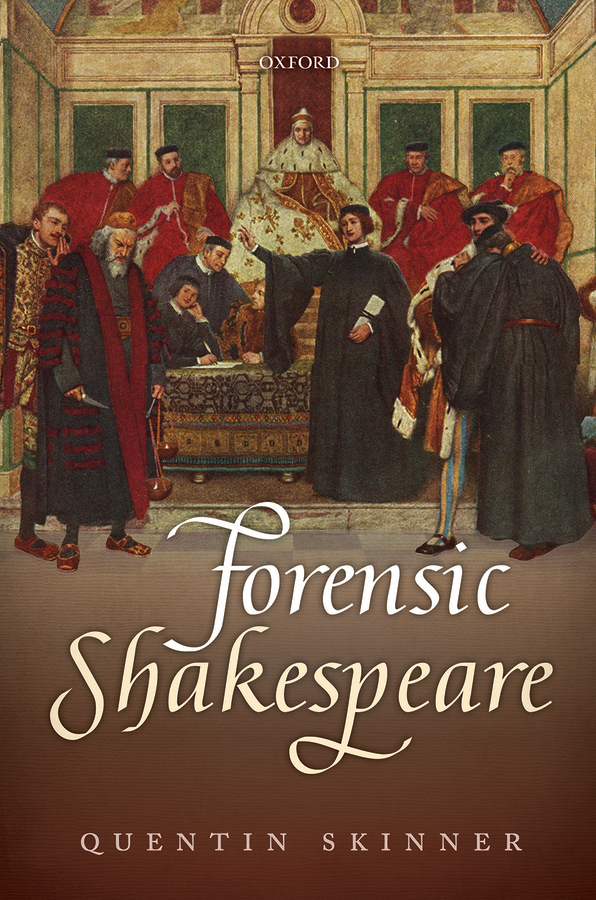

- Book:Forensic Shakespeare

- Author:

- Publisher:Oxford University Press, Incorporated

- Genre:

- Year:2018;2014

- City:Great Britain;Oxford;UK

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Forensic Shakespeare: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Forensic Shakespeare" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Forensic Shakespeare — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Forensic Shakespeare" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CLARENDON LECTURES IN ENGLISH

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox 2 6 dp ,

United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Quentin Skinner 2014

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2014

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in

a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the

prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted

by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics

rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the

above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the

address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014933919

ISBN 9780199558247

ebook ISBN 9780191056642

Printed in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and

for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials

contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

I first presented the argument of this book as the Clarendon Lectures at the University of Oxford in the Hilary Term 2011. I feel deeply honoured to have been asked to contribute to this series, and must begin by thanking those who made my visits to Oxford such an enjoyable as well as instructive experience. Richard McCabe and Seamus Perry were my official hosts, and both were warmly welcoming, as was David Norbrook, who organized a helpful seminar in connection with the lectures. Katy Routh of the Faculty of English took care of all practical arrangements with exemplary care and efficiency. I also want to express my gratitude to all those friends and colleagues who not only came to hear me, but in many cases supplied me with additional references, suggestions for improvement, much-needed encouragement, cakes and ale. My warmest thanks to Laura Ashe, Colin Burrow, Terence Cave, John Elliott, George Garnett, Claire Landis, Rhodri Lewis, Laurie Maguire, Noel Malcolm, Sarah Mortimer, Keith Thomas, Bart van Es, Jeremy Waldron, David Womersley, and Brian Young. To Andrew McNeillie I owe a special word of thanks for having proposed that I be invited to deliver the lectures, and for continuing to show so much faith in my work.

I presented a revised version of my argument as the Clark Lectures at Trinity College Cambridge in the Lent Term 2012. This too was a series to which I felt deeply honoured to contribute, and I am very grateful to Boyd Hilton and Richard Serjeantson for putting forward my name. My hosts at Trinity College were Caroline Humphrey and Martin Rees, and I was magnificently entertained. Adrian Poole was another welcoming presence in the college, and chaired a further helpful seminar at the end of the series. To Richard Serjeantson I owe additional thanks for organizing the lectures, and for presiding at the splendid dinner after my final talk. During my weekly visits to Cambridge I also benefited from many conversations with friends and colleagues who generously attended my lectures, including Gavin Alexander, Michael Allen, Annabel Brett, John Dunn, Richard Fisher, Raymond Geuss, Heather Glen, Fred Inglis, John Kerrigan, Subha Mukherji, Jeremy Mynott, David Reynolds, John Robertson, John Thompson, and Phil Withington. For subsequent encouragement and advice about my project I am greatly indebted to Akeel Bilgrami, Stephen Greenblatt, Peter Mack, Kari Palonen, Christopher Prendergast, David Sedley, Cathy Shrank, B. J. Sokol, James Tully, and Martin Wiggins. I owe particular thanks to Brian Vickers, who provided me with indispensable help in matters of dating and bibliography. I should also like to take this opportunity to say how much I owe to Christopher Ricks, from whom I never cease to learn.

I started thinking about this book after taking part in two conferences in 2006. The first was organized at Cambridge by Sylvia Adamson, Gavin Alexander, and Katrin Ettenhuber, who were then in the process of editing Renaissance Figures of Speech.

I began the process of writing after moving from the University of Cambridge to Queen Mary, University of London in 2008. Queen Mary has proved an ideal place in which to work. I am profoundly grateful to Philip Ogden, then Vice-Principal, for inviting me to join the college, and more recently for the helping hand of Morag Shiach as Dean of the Humanities and Social Sciences. These may be dark days for the humanities, but at Queen Mary I could not have received a brighter welcome. I am also blessed with outstanding colleagues, and I want to thank Richard Bourke, Warren Boutcher, and David Colclough for many discussions about my research.

I finished what I hoped was a final draft in the summer of 2013 and circulated it to a number of readers. I name them with deep gratitude: Colin Burrow, David Colclough, Lorna Hutson, Susan James, John Kerrigan, Jeremy Mynott, Eric Nelson, Markku Peltonen, Neil Rudenstine, and John Thompson. They provided me with many new ideas and much generous encouragement, but they also made it clear that my manuscript needed to be extensively revised. Colin Burrow showed me that the tone as well as the direction of my argument required reconsideration in many places. Lorna Hutson enabled me radically to improve the balance of the book by pointing out the vital importance of Lucrece. And John Kerrigan, who talked to me extraordinarily illuminatingly about my lectures, persuaded me that there were many things I simply could not say, thereby rescuing me from a number of absurdities.

I was able to make the necessary revisions during a year of sabbatical leave from Queen Mary, which I spent as Visiting Professor attached to the Center for Human Values at Princeton University in 201314. I am greatly indebted to Charles Beitz and his committee for inviting me, and grateful for many conversations with members of the Center and others associated with it, among whom I particularly want to mention David Ciepley, Melissa Lane, Tori McGeer, Philip Pettit, and Alan Ryan. To Nigel Smith of the Department of English I am grateful not merely for enlightening conversations, but also for putting me in touch with two remarkable PhD students, Andrew Miller and Daniel Blank. Both read the final draft of my manuscript with meticulous attention, checking all my quotations from Shakespeare as well as all my references and correcting many embarrassing mistakes. The Center generously paid for this wonderful help, and I owe many thanks to the Assistant Director, Maureen Killeen, for making the necessary arrangements.

The working lives of those who study early modern texts have been transformed in recent times by the availability of online concordances and databases, among which Early English Books Online is a resource to which we all owe a large and growing debt. But the rare book rooms of the great libraries remain indispensable, and I am happy to record how much I have once again profited from the expertise of the staff at the British Library, the Cambridge University Library, the Library of the Faculty of English at the University of Cambridge, and the Firestone Library at Princeton.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Forensic Shakespeare»

Look at similar books to Forensic Shakespeare. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Forensic Shakespeare and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.