Cook - Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present

Here you can read online Cook - Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Lanham u.a, year: 2014, publisher: Lexington Books, a division of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., genre: Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present

- Author:

- Publisher:Lexington Books, a division of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- City:Lanham u.a

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Cook: author's other books

Who wrote Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

All the editors and authors whose work has gone into this volume were formerly the doctoral students of an extraordinary pair of advisors: Joseph W. Esherick and Paul G. Pickowicz. The program in modern Chinese history that they built at the University of California, San Diego, was a unique experience for all who participated. The countless talks, research trips, conferences, and wonderful gatherings they put together infused the program with a spirit of human warmth and intellectual dialogue that extended well beyond the classroom. But the most important element of Joe and Pauls approach to graduate teaching was their commitment to collaborative mentorship. Their cooperative ethic made them truly equal professional partnersthey served as co-advisors for every studentand provided a model of teamwork and selflessness to their many grateful advisees. We offer this volume, designed primarily for use in the classroom, as a tribute to our experiences in Joe and Pauls program, and to their amazing capacity for investing boundless energy in each and every student.

Joe and Paul, we thank you.

James A. Cook, Joshua Goldstein, Matthew D. Johnson, and Sigrid Schmalzer

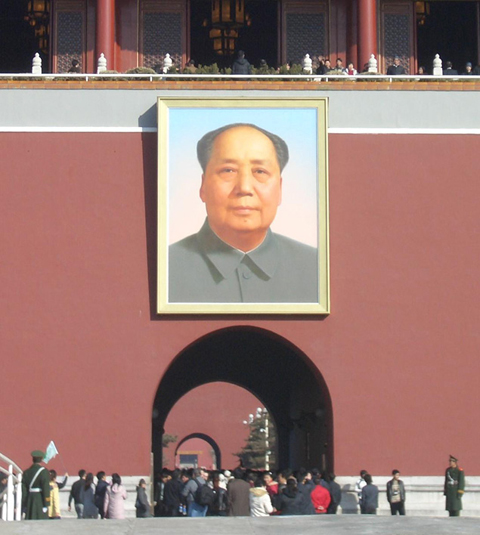

If a single image could be said to be the icon of modern Chinese history, it would probably be this portrait of Chairman Mao (). Maos portrait has been reproduced literally hundreds of billions of times: on untold millions of Mao buttons and propaganda posters of the Cultural Revolution (19661976); on rearview mirror ornaments, tee-shirts and cigarette lighters; on Chinese currency (his gentle smile graces every bill of legal tender in China today); and, most famously, on Tiananmen Gate in the heart of Beijing, where he surveys the enormous public square beneath and all who pass through it. This portrait of Mao has been charged with so many vital political and cultural meanings that we would be remiss to discuss modern Chinese visual culture without at least giving a respectful nod to his all-but-disembodied head. Travelers from all over China and the world have made sure to get their photos taken beneath Maos oversized portrait. The acclaimed author Yu Hua recalls how important that photo op was for him as a teenager during the Cultural Revolution:

I used to have a photograph of myself when I was fifteen, standing in the middle of Tiananmen Square with Maos huge portrait visible in the background. It was taken not in Beijing but in the photography studio of our town a thousand miles away. The room in which I was standing cannot have been more than twenty feet wide, and the square was just a theatrical backdrop painted on the wall. When you looked at the photo, you might almost have believed I was really standing in Tiananmen Squareexcept for the complete absence of people in the acres of space behind me. This photograph crystallized the dreams of my childhood yearsand indeed, the dreams of most Chinese children who lived in other places than Beijing. Almost all studios then were equipped with this same tableau of Tiananmen...

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Mao Zedong overlooking Tiananmen Square. Diego Delso, Gate of Heavenly Peace, Beijing, China. 2006. Available from: Wikimedia Commons, License CC-BY-SA 3.0 (accessed December 19, 2013).

A potent icon indeed, when an image (a photo) of an image (a painted backdrop ) of the image (the portrait in Tiananmen), is still powerful enough to crystallize a dream.

What was that dream? Chinese people who experienced the political maelstrom of the Cultural Revolution have devoted memoirs, essays, n ovels , artworks, and films to unraveling the dreams and conflicts of that era, many highlighting the role that Mao played in Chinese peoples lives and psyches at the timenot just as a political leader, but as an idea and an image. The portrait that still hangs over Tiananmen today has long outlived that era, but over the ensuing decades it has accrued many new and often contradictory meanings, and Maos bust continues to provoke and inspire today, spawning a global-scale cottage industry of Mao-themed art that offers contradictory perspectives on the man, the revolution, and its aftermath. The reader will find dozens of these artworks and other images related to Mao and his iconic Tiananmen portrait (as well as a great deal of scholarly analysis of thes e images ) on the website that accompanies this volume (http://visualizingmodernchina.org).

We live, today, in an intensely visual culture. We learn, communicate, create, and seek leisurely escape through ever-proliferating modes of visual stimulationTV, film, smart phones, video games, online media, etc. Yet we rarely pause to consider that this experience of becoming visual has unfolded very differently throughout the world and thus bears the indelible marks of unique and specific histories. This volume is intended to encourage just such a consideration of the multiple forms and transformations of visual culture in another time and placeChina from the Qing empire (16441911) through the Republican era (19121949) to the Peoples Republic of China (1949present).

The chapters in this volume work explore key moments and themes in Chinas modern history through an analysis of visual records. Together, they challenge the common assumption that visual materials are merely ephemeral images that supplement the substance of history. Rather, the study of visual images requires that we think more broadly about visual culture and engage in critical analysis of image-making as a force in shaping historical dynamics . The study of visual culture has arisen fairly recently. Historians usually emphasize written texts over pictures; art historians, on the other hand, tend to elevate art over all other forms of media and experience. But throughout history both written texts and works of art have typically had quite limited audiences and functioned in quite limited contexts. Other forms of display and visualityparades and processions; domestic and public architecture; everyday clothing and decorations; nature, landscape, and its reconfigurations; and (more recently) magazine ads, personal photographs, and internet websiteshave had greater impact on a larger range of creators, viewers, and participants. The idea of visual culture encompasses this vast and changing range of visual materials.

Our goal as historians is not only to understand what certain historical images depict, but also to understand the changing ways that images have been produced, distributed, and experienced, as well as the intentions of their creators, the audiences they sought to address or to shape (loyal subjects, conscious citizens, nations, etc.), and the responses they elicited from those audiences. Of course, image-makersbe they governments, commercial interests, or individual artisansrarely leave records of what they meant to convey when commissioning or crafting particular images. Nor is it easy to uncover the conditions under which historical audiences may have encountered images, how they reacted to those images, and what effects images might have produced in their everyday lives. The analysis of historical images requires great care and ingenuity, hence the strong emphasis on methodology in this introduction and the chapters that follow.

While the subjects described in the essays here cover the eighteenth century to the present, visual culture in China is far from a mere three- hundred -year young. For at least two millennia, Chinese emperors used sumptuous court ritual and elaborate visual displays to establish their authority . In China, as elsewhere, political rulers and social elites sought to control symbols, and with them, culture. Moreover, China was historically on the cutting edge in developing printed media, with woodblock printing spreading both texts and images on a large scale from at least the Song dynasty (9601279), if not earlier. Still, this primarily text-based media reached mainly an elite literate minority. Often far more influential were cultural displays that could reach literate and illiterate populations alike, such as the massive commissioned statues, temples, and palaces that contributed to a visually opulent elite culture in imperial capitals like Changan, Kaifeng, Hangzhou, and Beijing.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present»

Look at similar books to Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Visualizing modern China: image, history, and memory, 1750 - present and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.