Contents

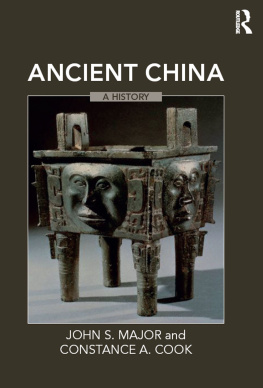

Ancient China

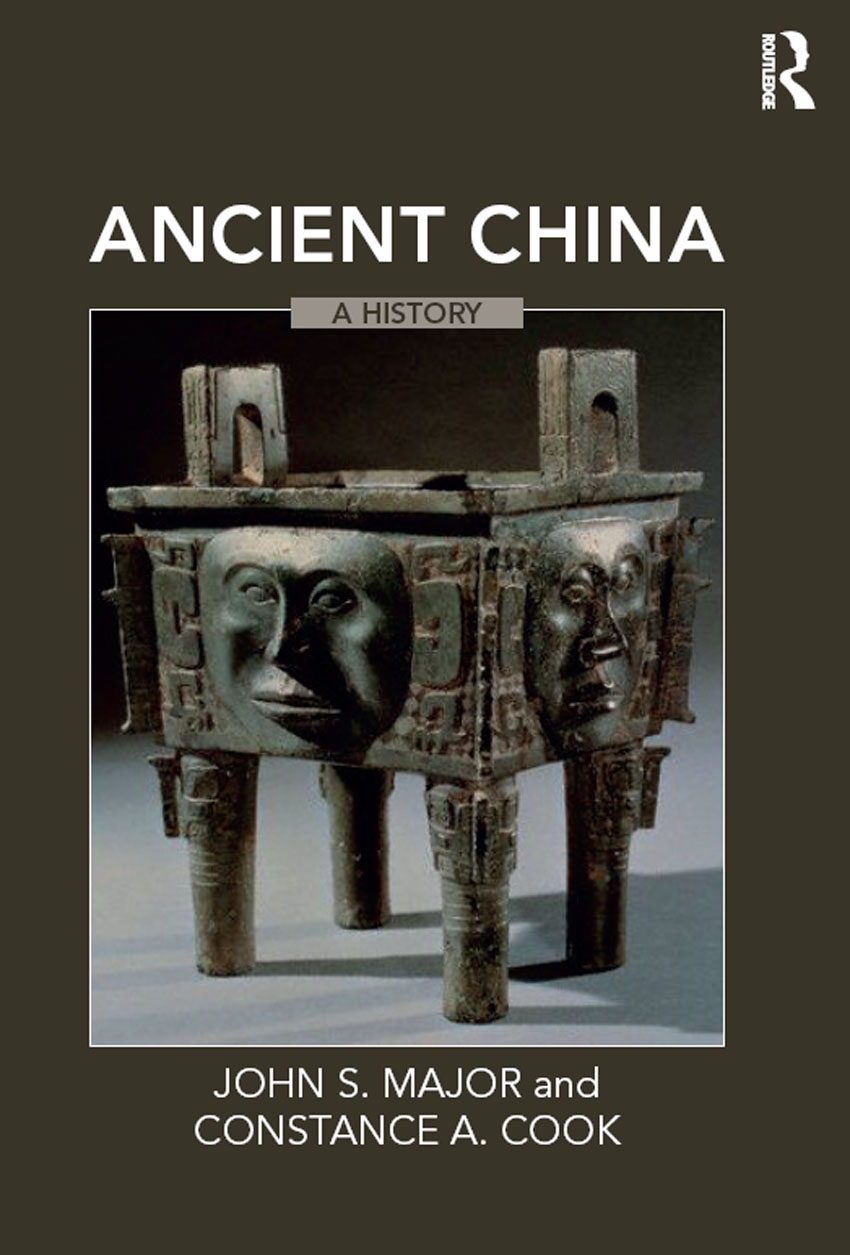

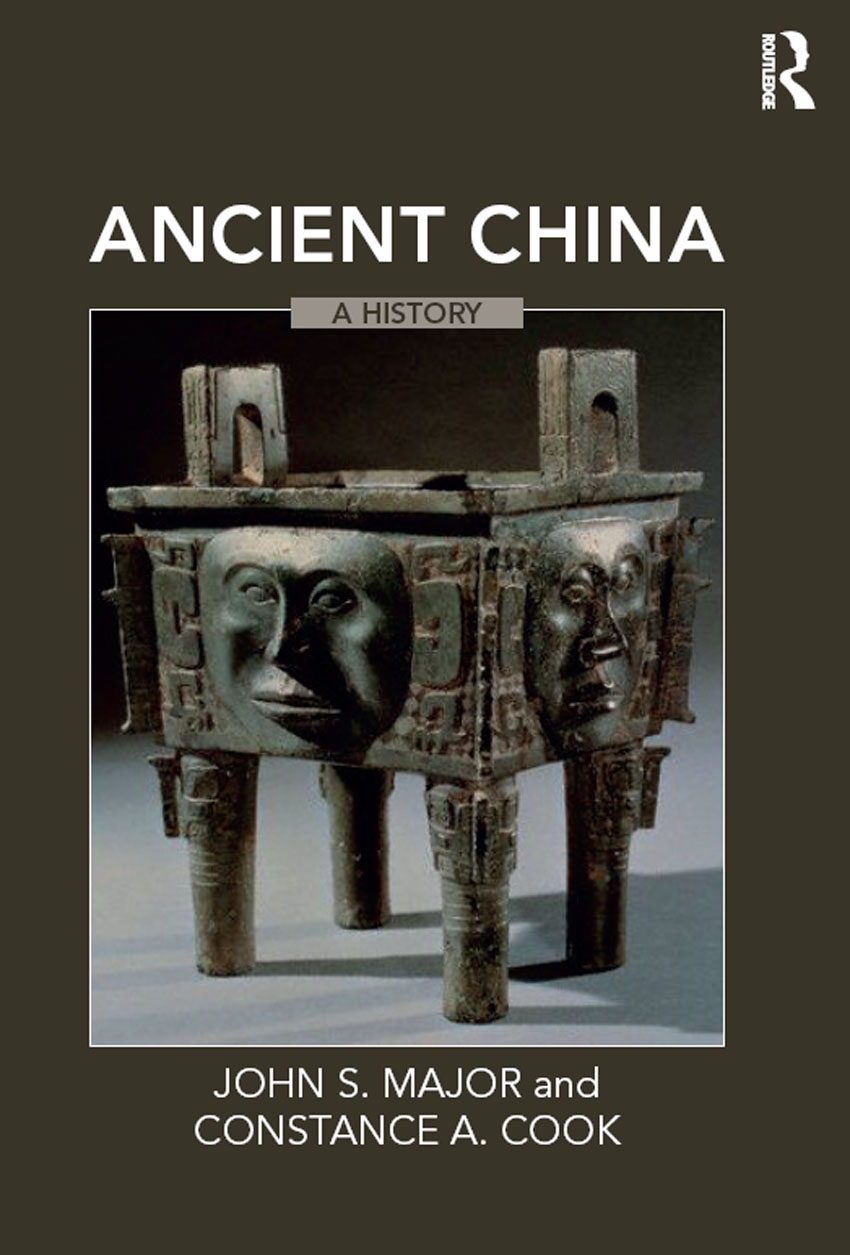

Ancient China: A History surveys the East Asian Heartland Regionthe geographical area that eventually became known as Chinafrom the Neolithic period through the Bronze Age, to the early imperial era of Qin and Han, up to the threshold of the medieval period in the third century CE. For most of that long span of time there was no such place as China; the vast and varied territory of the Heartland Region was home to many diverse cultures that only slowly coalesced, culturally, linguistically, and politically, to form the first recognizably Chinese empires.

The field of Early China Studies is being revolutionized in our time by a wealth of archaeologically recovered texts and artefacts. Major and Cook draw on this exciting new evidence and a rich harvest of contemporary scholarship to present a leading-edge account of ancient China and its antecedents.

With handy pedagogical features such as maps and illustrations, as well as an extensive list of recommendations for further reading, Ancient China: A History is an important resource for undergraduate and postgraduate courses on Chinese History, and those studying Chinese Culture and Society more generally.

John S. Major taught East Asian History at Dartmouth College, US, from 1971 to 1984. Thereafter he has been an independent scholar based in New York City, US.

Constance A. Cook is Professor of Modern Languages and Literature at Lehigh University, US.

Ancient China

A history

John S. Major and Constance A. Cook

First published 2017

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 John S. Major and Constance A. Cook

The right of John S. Major and Constance A. Cook to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

A catalog record for this book has been requested

ISBN: 978-0-7656-1599-2 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-0-7656-1600-5 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-71532-2 (ebk)

Typeset in Times New Roman

by Sunrise Setting Ltd, Brixham, UK

Contents

All maps by Jien Zhang, with data from China Historical Geographic Information Service (CHGIS), Center for Geographic Analysis, 1737 Cambridge Street, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138.

The quotation in Chapter 6 from Bernard Karlgren, The Book of Documents (Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities 22; Stockholm, 1950), pp. 556 (modified JSM), is used courtesy of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm.

John S. Major taught East Asian history at Dartmouth College from 1971 to 1984. Thereafter he has been an independent scholar based in New York City. An authority on the intellectual history of the Han dynasty, he is the co-translator (with Sarah A. Queen, Andrew Seth Meyer, and Harold D. Roth) of The Huainanzi (2010), co-translator (with Sarah A. Queen) of the Chunqiu fanlu (Luxuriant Gems of the Spring and Autumn), and co-author and co-editor, with Constance A. Cook, of Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China (1999). In addition to his scholarly works on early China, he has published widely in other fields, including books for young readers, local and family history, and the pleasures of reading.

Constance A. Cook is Professor of Modern Languages and Literature at Lehigh University. She specializes in the study of excavated texts from ancient China. She is co-author and co-editor, with John S. Major, of Defining Chu: Image and Reality in Ancient China (1999), author of Death in Ancient China: The Tale of One Mans Journey (2006), and author of Ancestors, Kings, and the Dao (2017). In these and other publications she focuses on the examination of excavated texts in the context of material culture and what they can tell us about belief systems and local social practices.

There was no such place as China for most of the time period covered by this book. Long before China arose as a concept, a place-name, and a political reality, a variety of cultures, polities, and states occupied parts of the physical landscape that we now know as China (). Some of the first manifestations of such cultures could be called proto-Chinese or Siniticthat is, showing characteristics that would later be identified with Chinawhile others clearly stood apart from the Chinese ethno-cultural world. The name China itself apparently comes from the state of Qin (pronounced chin), which in 221 BCE completed the forcible unification of the various states that occupied the Yellow River Plain and the Yangzi River Valley, imposed central rule upon them, and created the first authentic imperial Chinese state. But a succession of proto-states and kingdoms had existed in parts of that territory for some 2,000 years before Qin gave rise to China, and Neolithic cultures had existed there for thousands of years earlier. Indeed, human existence in various places in East Asia can be documented back over 50,000 years. How, then, is one to refer to China before China? And why does it matter?

It matters because the use of such terms as North China for the territory of the Shang kingdom (c. 15551046 BCE), or Far Western China for the Tarim Basin (the home of what seems to have been the easternmost outpost of the ancient people who would later be known as the Celts), tends to homogenize ancient history and obscure the diversity of the ancient East Asian world. It falsely suggests the existence of China as a political entity in very ancient times. And it obscures the reality that what is known as Chinese culture today has diverse regional and cultural roots.

Ancient China, as historians commonly use that term, refers to the period from the beginning of the Neolithic era, about 10,000 years ago, to the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty in 220 CE. Early China, in common usage, is a more restrictive term, used for the period from the Early Bronze Age to the end of the Eastern Han. The Three Kingdoms Period, 220265 CE, marks the transition from Early China to Medieval China. In this book, we will generally avoid using the word China to refer to the period before 221 BCE. Instead we will refer to sociopolitical entities as they existed at any given time (for example, the Shang kingdom or the state of Lu), and locate them by using terms that refer to specific geographical features (the Yellow River Plain, the South-Central Coastal Region) rather than by such terms as east-central China or the North China Plain. Fortunately many Chinese place-names are geographically specific (such as the province names Shandong, east of the mountain, and Hunan, south of the lake), allowing us to use them freely within our frame of reference.