Birth in

ANCIENT CHINA

SUNY series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture

Roger T. Ames, editor

Birth in

ANCIENT CHINA

A Study of Metaphor and Cultural Identity in Pre-Imperial China

Constance A. Cook and Xinhui Luo

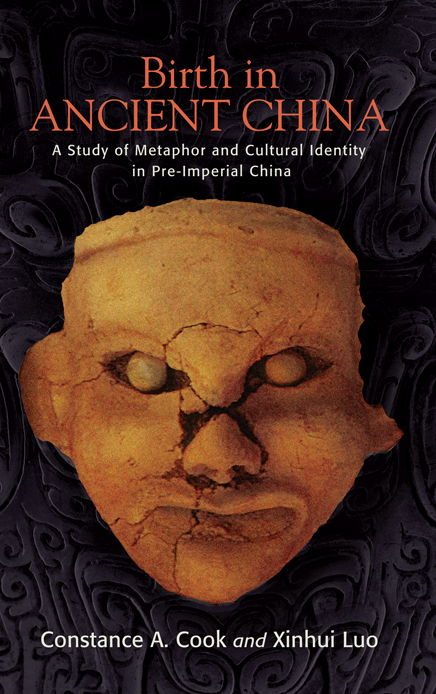

Cover image of face from Hongshun ritual site. Photo by Tian Shuai. Courtesy of the National Museum of China.

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany

2017 State University of New York

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

For information, contact State University of New York Press, Albany, NY

www.sunypress.edu

Production, Ryan Morris

Marketing, Kate R. Seburyamo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Cook, Constance A., author. | Luo, Xinhui, co-author.

Title: Birth in ancient China : a study of metaphor and cultural identity in pre-imperial China / Constance A. Cook and Luo Xinhui.

Description: Albany : State University of New York Press, [2017] | Series: SUNY series in Chinese philosophy and culture | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016054534 (print) | LCCN 2016057612 (ebook) | ISBN 9781438467115 (hardcover : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781438467122 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ChildbirthSocial aspectsChinaHistoryTo 1500. | Birth customsChinaHistoryTo 1500. | Human reproductionSocial aspectsChinaHistoryTo 1500. | MetaphorSocial aspectsChinaHistoryTo 1500. | Group identityChinaHistoryTo 1500. | ChinaSocial life and customsTo 221 B.C. | ChinaHistoryZhou dynasty, 1122221 B.C.

Classification: LCC GN482.1 .C66 2017 (print) | LCC GN482.1 (ebook) | DDC 392.1/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016054534

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

Constance Cook is grateful for the support of the International Consortium for Research in the Humanities, Friedrich-Alexander-Universitt Erlangen-Nrnberg, Germany. Both authors wish to thank Tian Shuai and Hu Wenjia for their research help.

Introduction

A Chu Text

Birth is naturally a gendered phenomenon. Only a mother can give birth and only people labeled females can be mothers. In this sense, the idea of womanhood has always been intimately associated with the physical reproduction of society. Reproduction of society, history, and the ability to have a future all relied on women. The heavy hand of later editors, particularly those of Han and later Ru or Confucian scholars, upon pre-imperial texts requires us to balance information provided by recently discovered bamboo and silk texts and other excavated texts, such as bone and bronze inscribed texts, against what is preserved in the transmitted classics. Material culturethat is, artifacts and burial datacan also provide hints.

The text, the Chu ju , that inspired this analysis of the female birth process is a recently discovered fourth-century BCE bamboo manuscript that likely originated from the middle Yangzi region, a product of a Chu scribe (the text is translated at the end of the introduction and analyzed in more detail in is among the historic, poetic, and divinatory texts preserved by Tsinghua University that were originally stolen by thieves from an ancient tomb. This text clearly connects birthing to lineage creation and political identity. It is remarkable because it not only provides a history of the mostly male Chu royal lineage in rhythmical prose and all its capitals up to 381 BCE, but it also includes the earliest detailed description of a female traumatic birthing experience, one that in modern times would be understood as a cesarean section. We explore the connection between birthing myths and royal genealogy as well as the cultural symbolism of the cutting or splitting open of the mothers body. But first, to put this Chu text into a larger religious and mythical context, we examine the earliest records, those produced by the Shang people during the second millennium BCE up through the time of the third-century BCE Chu text. The elite wished to control fertility, the success of the pregnancy, as well as the gender and future prognosis of the baby. Because of the religious belief structure at the time, this process included appeals to the supernatural. Chinas earliest birthing records are mostly preserved in divination records, oracle bones, and bamboo stalk divination manuals and almanacs, or Day Books ( Rishu ), as well as in silk medical manuscripts and some transmitted texts.

In , we compare the legends of good and bad births and their cultural affiliations and note how cultural conflicts ironically preserve evidence for early surgical procedures for difficult births. Through a subtle examination of early Chinese materials, our overall study teases out the unknown history of ancient womanhood and womens role in the social reproduction of early Chinese patriarchy.

We analyze the meaning behind the names of these ancestors in terms of the larger birthing narrative in early China.

Only the first section of the Chu ju mentions the role of birth mothers in the creation of a people. The rest of the manuscript is presumably devoted to male rulers and the names of their capitals. We are concerned with the initial section. Although scholars still debate how to read some of the archaic graphs, since the content of this text frames all the discussions in this book, we first provide an English translation and follow this with a detailed analysis with the Chinese in :

Ji Lian at first descended onto Gui Mountain going to Xueqiong (a cave). Once he came out (from Xueqiong) to Qiao Mountain, he resided at Huanpo (a slope). Then he went up the Chuan River and had an audience with Pan Gengs daughter, who resided at Fang Mountain. Her name was Ancestress Wei (Bird?) and she had grasped the virtue of compassion. She wandered throughout the Four Regions. Ji Lian heard that she sought marriage, so he pursued her as far as Pan. Thereupon, she gave birth to Ying Bo (Elder Son Ying) and Yuan Zhong (Middle Son Yuan). The delivery was normal and auspicious. From early on they resided in Jingzong (Capital-Main Shrine).

Later on, Xue Yin (Ji Lians descendant, a third son, Cave Drinker) journeyed to Jingzong, whereupon he heard about Ancestress Lie (Break Apart, or Li) in the Zai River region. She was mature with long delicate ears, so he took her as a wife and she gave birth to Dou Shu (Middle Sibling Dou) and Li Ji (Youngest Son Li). Li did not follow (Shu down the birth canal) but came out through a split in her side. Ancestress Lies (spirit) went to visit Heaven. Shaman Xian cut into (sewed? wrapped? confronted the demon in?) her side with a thorn(s?), hence the modern term chu ren , the People of the Thorns.

The complex imagery of meeting the young women in wild areas of mountains and rivers, of their smooth versus traumatic birthing of twins, of the use of thorns by shamans, and even the names of the people and places mentioned will be explored in greater detail in the following chapters. First, however, we will set up the social and religious context in which this tale of the birth of a people was imagined.