Introduction: Politicized Histories in Modern China

Ying-kit Chan, Leiden University

Fei Chen, Shanghai Normal University

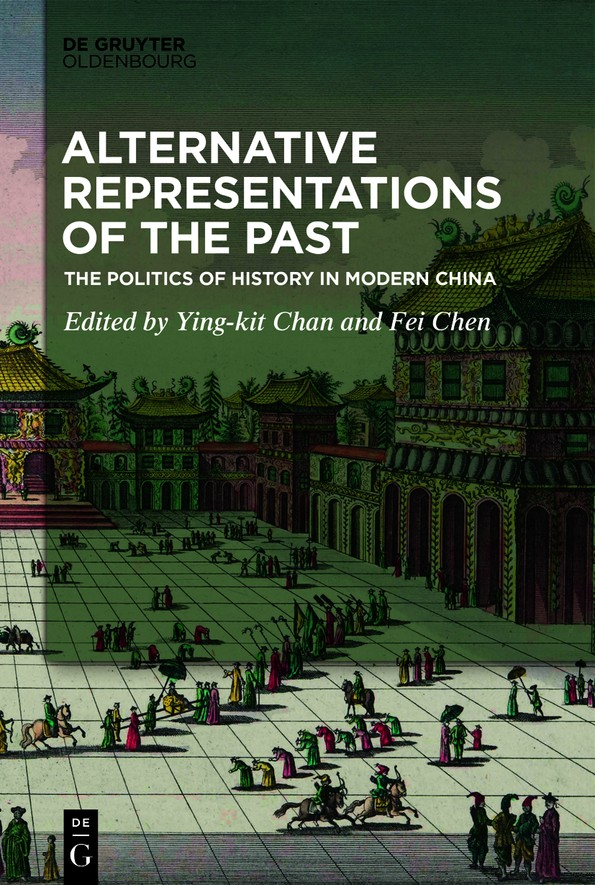

This book is about representations of the past and what they reveal about their creators and their audience. Modes of representations arise and decline according to the shifting needs and tastes of the present. In eighteenth-century Europe, a Chinese-inspired stylistic trend known as chinoiserie followed a similar pattern. Travel to Asia was difficult and limited to a small group of explorers, missionaries, soldiers, traders, and colonial administrators, who fueled the imaginations of others with their accounts that described the splendor and oddities of Oriental civilizations. Inspired by these travelogues and the curios that appeared in increasing quantities in the marketplace, creators of art selected aspects of gardens, furnishings, and porcelains that they thought would fascinate patrons of their work. An example of such artwork is shown on the book cover. Created by a little-known Dutch painter who apparently had never visited China, the painting of what seemed to be the imperial palace or Forbidden City in Beijing featured motifs that would strike his audience as instinctively Chinese. With the benefit of hindsight, similar perhaps to the experience of nineteenth-century Europeans who had more direct and intense exchanges with the Chinese, we are sufficiently informed to determine how mistaken that representation was. But the goal of the painter was never about representing the real as accurately as possible he would not have dared to produce his work if that had been the case. It had more to do with gaining the recognition and support of his audience, for reasons that were more practical than portraying a realistic China that he could only imagine.

This book presents a critical reflection on the relationship between the past and historical writing. At the risk of stating the obvious, whatever is written as history is not synonymous with the past, which is strictly a temporal concept alluding to things that existed or occurred prior to the historical present. As a book on representations, the present volume does not seek to ascertain the accuracy of writings about the past. All representations are almost by default a form of epistemic violence toward the past or text (both written and non-written) that they claim to inherit and are, depending on the context, definition, or perspective, misrepresentations based on the fluid benchmark of historical accuracy. Rather than focusing on historiography or historical moments, then, the book concentrates on representations of the past related to modern China loosely defined here as the geobody of all the Chinese dynasties or empires combined. It reveals and challenges the workings of two dominant modes of historical writing in modern China: state-centrism and nation-centrism.

History, as a scholarly discipline manifested in professional historical writing, is not a contemporary reality. People who once lived left behind evidence of their existence, and the task of historians is to decipher the traces and produce coherent, credible accounts of human actions, behaviors, and consequences. Although many people would understand that history is not a mere mirror image of the past, history continues to be portrayed as an objective, truthful, and scientific representation of the past. In twentieth-century Europe and the United States, scholars of various disciplines reflected critically on the romanticized belief in history, with some of the most powerful critiques coming from the field of memory studies. This is perhaps unsurprising, given that, as literary scholar Richard Terdiman succinctly suggests, memory is the past made present. For sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, memory, when articulated, is collective and located in social practices. Private memories are fleeting and last only in the group context. Halbwachs invokes the concept of collective memory, which is embedded within a web of symbols, traditions, and power relations. Historian Pierre Nora, in his seminal volumes Realms of History, suggests that the social implications of collective memory are wider. According to Nora, memory and history are antithetical to each other: memory is alive and in a state of permanent evolution while history is the reconstruction of what no longer exists in lived reality; memory is multiple yet specific, plural yet individual, while history has a universal vocation. By prioritizing the individual over the collective in memory studies and distinguishing more sharply between history and memory, Nora transforms Halbwachss concept of collective memory into a master narrative for modern historiography. For Nora, that historians have consciously selected memories of the past for purposeful writing suggests that the formation of history eradicates memories that do not fit in the narratives of individual historians. History narratives endow otherwise unremarkable personal experiences and memories with depth and poignancy so that multiple lived experiences can be woven into a single national history. In response to what he sees as historys annihilation of memory and an increasingly fragmented world that is ruptured by the past and thus driven to consecrate sites embodying fading memories, Nora suggests that memories can be shared by a nation when they are emptied of any real significance and stop being divisive in other words, when they are hollowed and homogenized for reinterpretations that justify the nations origins and its linear, supposedly natural trajectory to its present state.

Notwithstanding his clarification of contradictory efforts by historians and nations to simultaneously destroy and rescue memories, Nora has inadvertently romanticized memory by equating it with authenticity and continuity while associating history with mediation and rupture. Inspired by the linguistic turn in humanities and social sciences since the 1970s, scholars such as Hayden White have tried to reveal the narrative or poetic nature of history, which can assume the form or presentation of memory. For them, both history and memory are invented traditions or mediated discourses. According to White, the doyen of philosophy of history who had, in fact, pioneered the linguistic turn in the study of historiography, historical work is a verbal structure in the form of a narrative prose discourse that purports to be a model, or icon, of past structures and processes in the interest of explaining what they were by representing them. Historians select, process, and arrange events into stories that are narrated via the plot structure of romance, tragedy, comedy, or satire and explained through formal, explicit, or discursive argument in order to express a certain ideology. As Whites analysis of historians rhetorical techniques suggests, historians invent history and maintain its validity.

Nevertheless, important differences exist between history and fiction, which are both constrained by the narrative format. The fundamental difference lies in whether either the creator or the audience believes that truth exists and can be conveyed through history, which, as the logic goes, is an objective restoration of the past. Historians are then responsible for ascribing truth or a mode of realism to history and converting their readers into believers in an objective past, all the while insisting on viewing the past through the lens of coherence and linear development. A long tradition of historical writing exists in what today is China, offering one of the best examples for understanding uses of the past beyond a mere recording of facts. Bound to a moral mission, Chinese writers of history sought to establish moral imperatives by writing about past characters and events from which they could extract lessons. Historical writing, from which analogies between comparable events in the past and the present could be established, also offered crucial precedents for formulating policies in its creators present. As illustrated by the obsession of dynastic rulers with producing official histories of their immediate predecessors, history supplied political legitimacy and continued to do so in twentieth-century China. Most Chinese dynasties had endorsed Confucianism as their state ideology, and Confucian ideology rests on the basic assumption that a state prospers when the ruler obtains the Mandate of Heaven and declines when the Mandate is lost. Although scientific historiography introduced from the West phased out Confucian historiography in the twentieth century, history continues to lend itself to various political agendas. And although scientific historiography diminished the moral meaning of history, history remains relevant when used to justify contemporary policies or furnish political legitimacy. In our own present, for authors in a socialist China that enforces strict censorship of speech and writing through the use of modern technologies denied to its imperial predecessors, political criticisms couched in matters of a bygone era are always safer than direct attacks on the present government, and Chinese peoples discussions of current politics are frequently turned toward historical analogy.