Cover design by Linda Ronan.

Text 2019 Larry Herzberg.

First printing 2019.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America.

Note to the Reader

China is the worlds most populous nation and has now become the number two economy in the world. Yet most people in the United States (and the rest of the Western world) know far too little about it. As a professor of Chinese language and culture over the past four decades, I have felt it increasingly important to point out many of the notable things about China, both in the past and in the present, that are generally an untold story. I have also made it my mission to correct many of the misconceptions that a great majority of Americans have about a country the U.S. is involved with more than ever before.

In this book I have attempted to introduce to a general audience some of the most significant and fascinating aspects of both ancient and contemporary China. Included are fifty-nine articles divided into three major sections: Chinas Past; Chinese Society, Culture, and Language; and China Today.

In the section on Chinas past are short commentaries about everything from the history of the Great Wall and the origin of silk, porcelain, and tea to the story of the only female emperor as well as the history of Chinese migration to the U.S. The section on Chinese society, culture, and language contains short essays about, for example, the nature of the spoken and written languages, the various ethnic groups within China, the major holidays, and superstitions regarding numbers. The final section on China today covers topics as diverse as the recent economic miracle, pollution, gender inequality, and Chinas emerging role on the world stage.

For the most part I have deliberately avoided controversial subjects such as human rights abuses or the perceived economic threat to the U.S. posed by Chinas rise. Those highly complex issues I did attempt to examine in a 2-hour documentary that my Chinese wife and I produced in 2012, entitled The China Threat: Perception versus Reality, which has been shared with hundreds of educational institutions in the U.S. (If you attend or work for a school, see the copyright page of this book for information about obtaining a complimentary copy.)

What I offer here instead is a glimpse into some of the defining aspects of China, both historically and in todays world. I have tried to make it interesting and entertaining while also providing some substantial educational value. This book was written for students of the Chinese language and culture and also for those traveling to China for business or pleasure who wish to learn more about the country they will be visiting. Above all, it is for anyone who aspires to deepen their knowledge of a country so very important in the times in which we live. I hope you will discover how much there is about China that is absolutely intriguing and worth learning about.

Larry Herzberg

Professor of Chinese

Director of Asian Studies

Calvin College

Grand Rapids, Michigan

Chinas Past

Chinas Society,

Culture, and Language

China Today

1

Origin of the Word China

The word we use in English to describe the worlds most populous country actually bears no resemblance to the term the Chinese themselves use.

There are various scholarly theories regarding the origin of the word China. The traditional theory most popularly accepted today was proposed in the 17th century by Martino Martini, an Italian Jesuit missionary, cartographer, and historian who spent much of his life in China. Martini posited that China is derived from Qin (, pronounced chin), the name of the westernmost of the Chinese kingdoms during the Zhou dynasty and that of the succeeding Qin dynasty (221206 BC), under which the various kingdoms were first united.

However, some scholars now believe that the word China is actually derived from Cin, a Persian name for China popularized in Europe by Marco Polo. The first recorded use in English dates from 1555. In early usage, china as a term for porcelain was spelled differently from the name of the country, the two words being derived from separate Persian words. Both these words came from the Sanskrit word Cna, used as a name for China as early as AD 150. In the Hindu scriptures Mahbhrata (5th century BC) and Manusmti (Laws of Manu; 2nd century BC), the Sanskrit word Cna is used to refer to a country located in the Tibeto-Burman borderlands east of India.

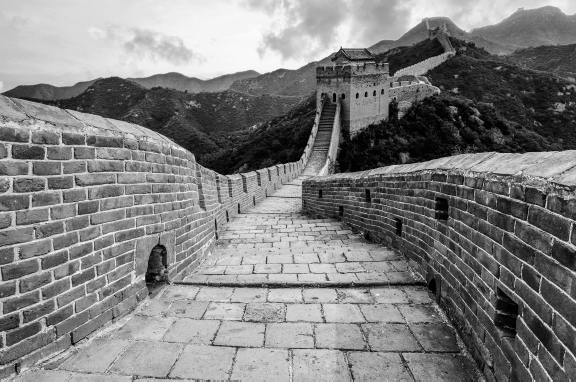

Even if the Jesuit Father Martini had been correct about the word China deriving from the name of the first Chinese dynasty, the Chinese people would never have called their country by that name in subsequent centuries. The Qin dynasty was by far the briefest of all Chinese dynasties. It lasted a mere fifteen years, ending only four years after the death of the First Emperor. During his eleven-year reign the first Qin Emperor did have some impressive accomplishments. He undertook gigantic projects, including ordering the building and unifying of various sections of what we now call the Great Wall of China to protect his new country from invasion by the barbarians to the north. He created a massive national road system. He also standardized weights and measures and even wheel ruts across all the kingdoms he administered. The Chinese writing system was also standardized for the newly unified country.

Most of this came at the expense of a great many lives. The building of the Great Wall and the national road system was only made possible through the conscripted labor of hundreds of thousands of peasants. These unfortunate men were often taken hundreds of miles from their villages to work many hard years on the frontiers. A large percentage of them never returned to their families but died in these forced-labor projects.

In order to avoid having antigovernment scholars compare his reign with the past, the Qin Emperor ordered most existing books be burned. The only exceptions were those on astrology, divination, medicine, and agriculture, as well as those that related the history of the Kingdom of Qin. The burning of so many books from the past also furthered the ongoing reformation of the writing system by removing examples of variant forms of Chinese characters. Most infamous of all was that this first of the worlds book-burning dictators had nearly five hundred scholars buried alive for illicitly owning such classic works as the Book of Songs and the Classic of History