Preface

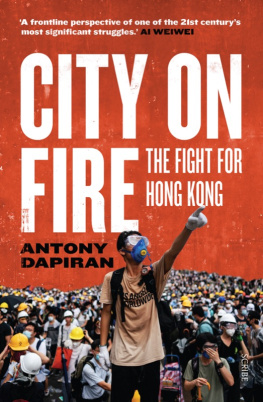

The mid-autumn afternoon sun has already sunk behind the office blocks of Hong Kongs Central business district.

I am standing in the midst of a crowd of thousands of protesters; collectively, we are blocking an eight-lane dual carriage highway. That morning, organisers had declared the beginning of the Occupy Central protest campaign and called upon Hong Kongers to join student protesters in demanding political reforms. Hong Kongers had responded in their thousands, flooding the streets and facing a police cordon that prevented them from joining the student protesters outside Hong Kong government headquarters.

On the far side of the police line, students wave back at the gathering crowds. The crowd calls for police to open the road so they can join the protesters inside police lines. Inexplicably given that opening access to the protest site would seemingly be the best way to clear the road the police continue to hold their line.

The pressure quickly intensifies as protesters, shielded with umbrellas, raincoats and cling film, begin pushing up against the police line, and police use pepper spray to force them back. To cries of Ze! Ze! (Umbrellas!), more umbrellas are passed through the crowd towards the front line.

Emergency access paths are opened up to enable people hit with pepper spray to make their way to the ad hoc first aid stations, marked by improvised cardboard First Aid signs, where volunteers rinse out the eyes of pepper spray victims. I see a man with a bright red face, eyes streaming with tears, as he staggers up from a first aid station and heads back towards the front line. He gives me a grin and says: Go again!

Behind their riot shields, I see the police slip on gas masks, I presume to protect themselves against stray bursts of pepper spray.

In the midst of this chaos, Democratic Party founder and senior statesman Martin Lee and pro-democracy media magnate Jimmy Lai come down into the midst of the crowd. They give speeches over a megaphone, calling upon people to persist but to avoid violence. Their speeches have only just ended when, without warning, there are several loud bangs and pops, and a cloud of smoke drifts over the crowd.

The realisation dawns on me slowly:

Thats tear gas.

Everyone seems frozen for a moment. Time stops. Then, as the cloud of smoke drifts lazily over us, the crowd breaks. We run.

An acrid smell, like gunpowder, drifts through the air. My cheeks tingle and my eyes begin to sting. I hold my breath and make for the far side of a nearby overpass where the air appears to be clear.

Are you okay? Someone in the crowd offers me water, a face mask and a wet towel.

More bangs and more clouds of gas as the police fire again.

Some people begin to throw water bottles and rubbish at the police, but are immediately held back by the crowd: Dont throw anything!

Through the rolling clouds of gas, a man emerges defiantly holding aloft two tattered umbrellas. His image is captured by press photographers and he becomes the movements icon: Umbrella Man.

But now, as the gas begins to disperse, the crowds come back and people regroup. They shout at the riot police:

Shame on you!

We are all Hong Kongers!

Take off your uniforms and go home!

The crowd moves in towards the police again. As the gathered masses shift and surge around me, a man to my left grabs my arm and says to me urgently: Hong Kong is dead!

*

Hong Kong is a city of protest. While the Umbrella Movement protests of 2014 captured the worlds attention, they were merely the latest and largest iteration of an ongoing series of political protests in Hong Kong stretching back decades, including a particularly lively recent past since the return of sovereignty to China in 1997. According to Hong Kong police statistics, there were 1142 public processions in 2015, equivalent to more than three per day, in the city of 7 million people.

Hong Kongers are renowned for being pragmatic, and there is indeed a pragmatic reason for protesting in Hong Kong: it often works. In many cases, protesters demands have been met, most notably overturning the Article 23 anti-subversion legislation in 2003, forcing Chief Executive Tung Chee-Hwas resignation following protests in 2004 and scrapping the Moral and National Education Curriculum in 2012. Over many years, Hong Kongers have been conditioned to view protest as an effective means of forcing political change in their city. According to a survey conducted by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, a quarter of Hong Kongs population agrees with the sentiment: Only radical action can get the government to respond to citizens demands.

However, this pragmatic explanation is only the beginning. There are deeper cultural and structural forces driving public protest in Hong Kong. In a city whose population identifies itself at least vis--vis its sovereign, the Peoples Republic of China by reference to the rights and freedoms it enjoys which the rest of Chinas population does not, protest is an embodiment of that identity, embracing as it does the freedoms of speech, expression and assembly.

Meanwhile, Hong Kongs protests have become a tourist attraction, with the Lonely Planet travel guides recommending Hong Kongs protest culture to their readers when naming Hong Kong one of their top destinations, painting a picture of a pseudo Mardi Gras atmosphere: Rallies are infused with theatrics and eruptions of song, dance and poetry, reflecting the citys vibrant indie music and literary scenes.

But beyond the spectacle itself, the vibrancy of Hong Kongs protest culture has a greater significance. The authorities tolerance of and reaction to public protests serve as a barometer of the health of the unique One Country, Two Systems principle under which sovereignty over Hong Kong was returned to China, as well as of Beijings disposition towards Hong Kong and its freedoms.

By extension, that reflects Chinas own future. Will Beijing permit the rest of China to become more open, a reflection of the Hong Kong experiment? Or will Hong Kong be forced to converge with an unyielding China as we approach 2047, the year when the fifty-year guarantee of Hong Kongs rights and freedoms expires?

The Umbrella Movement of 2014 was the crucible in which these questions were tested. Hundreds of thousands of protesters took to the streets to voice their demands for political reforms, blockading and occupying the business and commercial heart of the city for seventy-nine days. While the protesters demands at least for now have gone unanswered, the movement marked a new high point for political protest in Hong Kong.

The Umbrella Movement unfolded, literally, on my doorstep. My commute to my office in Central was transformed from a twenty-minute trudge along heavily trafficked roads into a daily carnival. Every night I would join the other curious office workers stopping by on the way home from work, picking my way between rows of brightly coloured tents on the occupied highway, browsing through the latest artwork or enjoying an ad hoc musical performance. Crowds would gather to listen to student leaders standing on the makeshift speakers platform, a plank between a couple of step ladders, addressing the crowd through a PA system powered by a diesel generator. On the side lines, a pensioner may deliver an impassioned political lecture, or a group of students engage in debate on the next steps for the movement.

The protests tore apart and remade the fabric of Hong Kongs urban landscape. The physical space itself, the highway reclaimed for the people, engendered a feeling of both transgression and liberation. In a city known for reclamations of land from the ever-shrinking Victoria Harbour, this was a real reclamation. There was a sense not of taking something, but of taking something