what an

exciting

book!

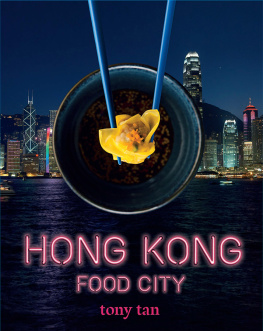

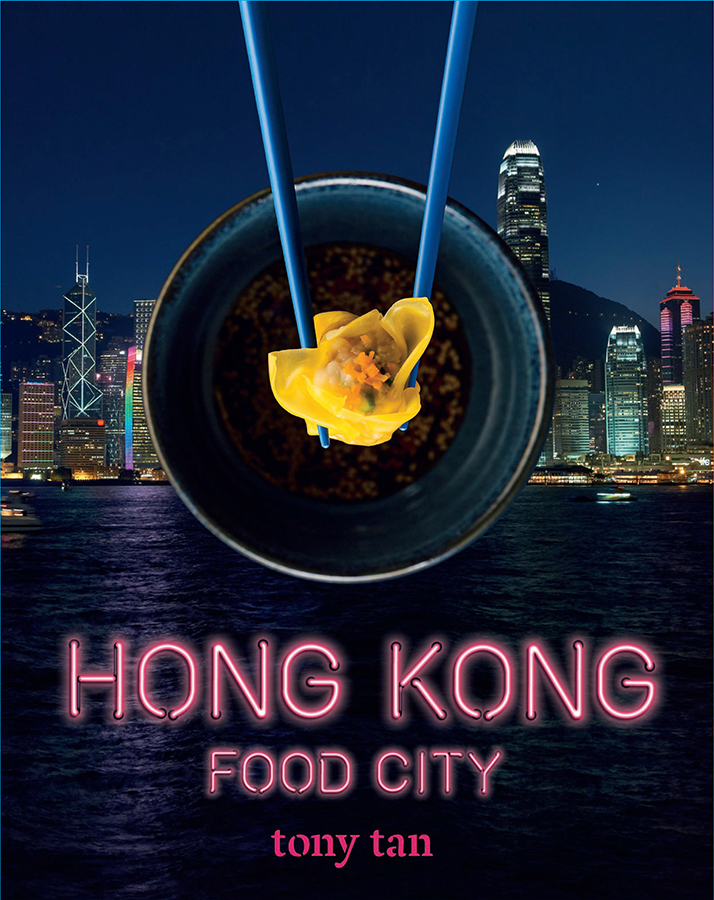

There can be no better guide to the glories of eating in Hong Kong than Tony Tan. Tony is known to many as an exceptionally talented cook; now he reveals himself as a fine writer and one who truly understands his subject. He is interested in history and tradition as well as flavour. Tony is a cooks cook. He never takes shortcuts; he explains and he reveals the full story. It helps that he is a fluent Cantonese and Mandarin speaker and as he jokes and banters with the stall holders at street food stands and markets, or the chefs of starred restaurants, you just know he is gathering insight and registering detail.

The recipes in this book include the very modern along with the traditional. There has been no watering-down of technique to please a Western reader. Rather, Tony has included meticulous explanations of Chinese ingredients and methods. Some of the recipes are challenging and almost certainly will require that the interested cook makes several visits to Chinatown to search out unknown ingredients. Which all just adds to the fun.

Anyone planning a trip to Hong Kong can follow Tonys recommendations to his favourite spots, ranging from the humble dai pai dong to the Michelin-starred Amber restaurant.

The photography is marvellous; not just Greg Elms images of mouth-watering food, but also the atmospheric street scenes of Hong Kong and its people by Earl Carter.

STEPHANIE ALEXANDER

a brief history

of Hong Kong

YOU CAN ALMOST FEEL THE RUSH OF PEOPLE IN HONG KONG, A CITY THAT SEEMS TO BE CHARGING ALONG IN OVERDRIVE. IT IS SPECTACULAR IN MANY WAYS.

A mere dot on the map, Hong Kong is one of the worlds top five financial centres, its glittering skyscrapers are a sight to behold and its renowned shopping centres cater to just about every whim and fancy. Bilingual and confident, on the arts front it is the envy of many Asian cities, and its food scene is truly a food lovers paradise. But Hong Kong was not like this less than two hundred years ago.

Hong Kong was built on power and colonisation. Hong Kong Island was ceded to the British by Chinas weak Qing emperors in 1842. A subsequent war resulted in China also ceding Kowloon and Stonecutters Island in 1860. In 1898, fearing their fledgling colony could not defend itself unless they also controlled the areas north of Kowloon, the British negotiated a 99-year lease of the New Territories. Sovereignty reverted to China in 1997 when that lease ended.

During this 99-year period, Hong Kongs population grew exponentially. The colony enjoyed a stable political environment amid the chaos existing in mainland China, brought on by internal strife and encroachments by Japan and Western powers. In the decades leading up to the First World War, Hong Kong developed into an entrept for Chinese trade, with mercantile companies such as Jardine Matheson playing a major role. Meanwhile, the Qing dynasty was toppled by Dr Sun Yat Sen and, for a time, warlords ruled much of China. More refugees arrived in Hong Kong.

In the years approaching the handover in 1997, Hong Kongs free-trade status saw its economy grow steadily. However, it was not always smooth sailing. Despite the British laissez-faire attitude, continued political turmoil in China had an impact. Hong Kongs lowest point was the Japanese occupation from 1941 to 1945, which led to much hardship and forced evacuation to China. But Hong Kongs fortunes changed with the Chinese civil war between the Communists and Nationalists. The 1949 Communist takeover led to another massive influx of refugees, both rich and poor. Affluent businessmen and tycoons from Shanghai set up labour-intensive industries in their new home, including textile and plastic toy manufacturing. This shift to manufacturing proved to be the saviour of Hong Kongs battered economy.

By the 1960s, with industrialisation and trade spearheading the way, Hong Kongs economy boomed and the citys food changed with it, although there were curious anomalies in the early days. The tastes of the British establishment meant that gammon, roast beef, tinned oatmeal and claret often graced the table. Life revolved around tennis, cricket, clubs, afternoon teas and drinks in classy hotels such as the Peninsula, which opened in the late 1920s. The British viewed the food of the Chinese with suspicion perhaps due to chauvinism or simply an inability to adapt to local tastes.

The Chinese, on the other hand, bound by colonial policies and restrictions, stuck to their teahouses, street stalls, markets and burgeoning restaurants to the west of the island in Sheung Wan and Sai Ying Pun. They also enjoyed Western foods in restaurants opened by their compatriots during the late 19th century. One of these is Tai Ping Koon restaurant. Featuring Western classics with a dash of Cantonese flair, these places came to be known as Soy Sauce Western restaurants. The use of Worcestershire sauce in Cantonese cooking could have started in that period. Full of fascinating flavours, the cross-cultural offerings included Swiss chicken wings, smoked pomfret and a giant souffl that still captivates all who dine there today.

With new-found wealth, people ate out more and different eateries emerged. The citys predominantly Chinese population was obsessed with food, and had an innate sense of appreciation for it, stemming from thousands of years of culinary evolution based on yin-yang principles, creativity and regional variations. Hong Kongs Chinese food scene was extraordinary even in the late 1950s and early 60s.

Dai pai dongs , meaning big licence stalls, were created by the colonial administration to help families of injured or deceased civil servants after World War Two. They joined the throng of hawker stalls, serving anything from comforting congee to restaurant-quality food. Springing up everywhere from alleyways to under trees, these alfresco eating spots quickly became crowd favourites. However, over the years, complaints about noise and hygiene have forced large numbers of them into government-run food centres. Some, such as the ever-popular Leaf Dessert and Sing Heung Yuen in Central, are still operating street side. Tung Po, made famous by Anthony Bourdain, in North Points wet market is one of the best dai pai dong experiences.