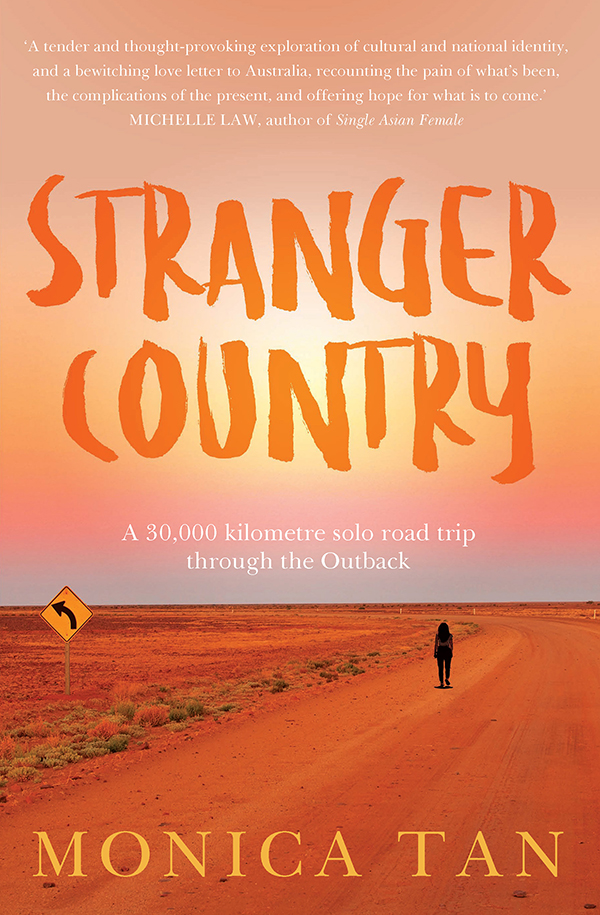

A tender and thought-provoking exploration of cultural and national identity, and a bewitching love letter to Australia, recounting the pain of whats been, the complications of the present, and offering hope for what is to come. Tans curiosity and deep reverence for the land and its first inhabitants makes her the perfect travel buddy on this journey into the heart of Australia.

Michelle Law, author of Single Asian Female

With 85 per cent of Australias population scattered along the coast, too often we look out and across the sea for meaning and adventure. Monica Tans Stranger Country is a call for us to look within: at our rich and varied geography, our long and buried history of diversity, and the 60,000-year-old culture on our doorstep. The clich that Australia has no history or culture is falsewe just dont often take the time to tell it. Stranger Country does. A necessary Australian story.

Rachel Hills, author of The Sex Myth

Self-aware and provocative, Monica gets to the heart of what it means to call Australia home as a non-Indigenous person. Never self-indulgent, Monica looks outwards and examines herself critically as she learns about the culture of the country she grew up in. I loved it, and came away with a new lens through which to see myself.

Bridie Jabour, journalist and author of The Way Things Should Be

Stranger Country is a marvellously engaging, beautifully described record of a quest into the meaning of belonging, that documents both the gritty reality of a 30,000-kilometre solo road trip around Australia by one young woman, and her profoundly intelligent journey of mind.

Isobelle Carmody, author of The Obernewtyn Chronicles

First published in 2019

Copyright Monica Tan 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email:

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76063 221 2

eISBN 978 1 76087 079 9

Internal design by Bookhouse, Sydney

Internal images from the authors collection

Map by Julia Eim

Set by Bookhouse, Sydney

Cover design: Christabella Designs

Cover images: Shutterstock

To my Australian Studies students, past, present and future.

I acknowledge and pay my respects to the elderspast, present and emergingof every nation through which I travelled on my road trip. I acknowledge that I live, work and study on Darug, Eora and Guringai Country.

I would like to extend the protection and care of my ancestors to any Indigenous Australians in China, just as their ancestors have taken care of me.

Contents

This book documents a 30,000-kilometre solo road trip I took around Australia in 2016. To write this book I relied on eighteen journals I penned over the course of those six months, along with hundreds of photos, additional research and my memories.

Although I spent the majority of my six months on the road in central and northern Australia, this should not be read as any reflection or validation of the commonly held belief that the Indigenous Australian cultures located there are more authentic than those in other parts of Australia. Rather, I chose to spend more time in those areas because they were less familiar to me than southern and eastern Australia. I considered this trip a rare opportunity for me to explore parts of Australia that are physically distant and difficult to access for a Sydney-sider.

Almost every person in this book was given the opportunity to review the passage in which they featured and suggest changes. In a small number of cases, I wasnt able to make contact. My decision to include them wasnt made lightly and was based on a strong sense that their contribution is vital to the telling of this story.

Many but not all people featured in this book are under a pseudonym. Due to word constraints, many locations, people and events were omitted.

This is a true story and, I hope, a truthful one.

When I look back on growing up in Sydney, I dont recall meeting any Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people. This is despite the fact the city is home to the largest population of Indigenous Australians in the country. As far as Im aware, none of my neighbours, schoolmates, teachers or local shopkeepers were Indigenous people. They werent among the actors and pop singers on posters stuck to my bedroom walls. They werent the politicians I saw on television or the authors of books on my shelves. Throughout my childhood, adolescence and even my twenties, Indigenous Australia was just a concept to me, one that rarely had a presence in my life.

I was born in Australia to Chinese Malaysian parents. As teenagers in the early 1970s, they had separately migrated here from rural north Malaysia to study at university. They met and married in Sydney a decade later and raised their four children in the citys leafy and well-to-do north-west. My parents social circle rarely overlapped with Indigenous Australian social circles. In fact, from what I can recall barely any of my parents friends werent of Chinese heritage.

Like many non-Indigenous Australians, I was introduced to Indigenous Australia at school. My Year 8 history teacher would stand in front of the classroom with a thick textbook open in her hands like a hymnbook, intonating in a low drone. She would lick her forefinger to turn each page, and that was the cue for all us studentsalthough most had zoned outto do the same. Our textbook depicted the Aborigines in colonial sketches as fit, dark-skinned men holding spears. In the most prosaic of terms, the book stated that as the new settler society swept across the continent, some of these primitive people were shot but the majority died from introduced diseases, and almost all of those who remained were absorbed into white society. Indigenous Australians were apparently cleared away from the land in one fell swoop, leaving a clean slate upon which Australia could be founded.

What a shame, I thought, but I wasnt ashamed. Those history lessons left me with the impression that what had happened to Indigenous Australia was awful but inevitable. It was less an advanced human civilisation and more a quaint relic, an insubstantial society that had lived lightly on this continentno wonder it had been so quickly and easily smudged out by colonial forces.

My conscience was clear. At the time of colonisation, my ancestors were living in a China preoccupied with internal political instability and aggressive military action against the British. If you were going to blame anyone for what happened to Indigenous Australia, I decided, you should blame white Australians. And even then, could you? The colonisers were dead. Whats done is done.