MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

1115 Argyle Place South, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2015

Text all contributors, 2015

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Ltd, 2015

A version of Lorelei Vashtis essay was originally published in Kill Your Darlings issue 19 and a version of Dee Madigans essay was originally published on The Hoopla.

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

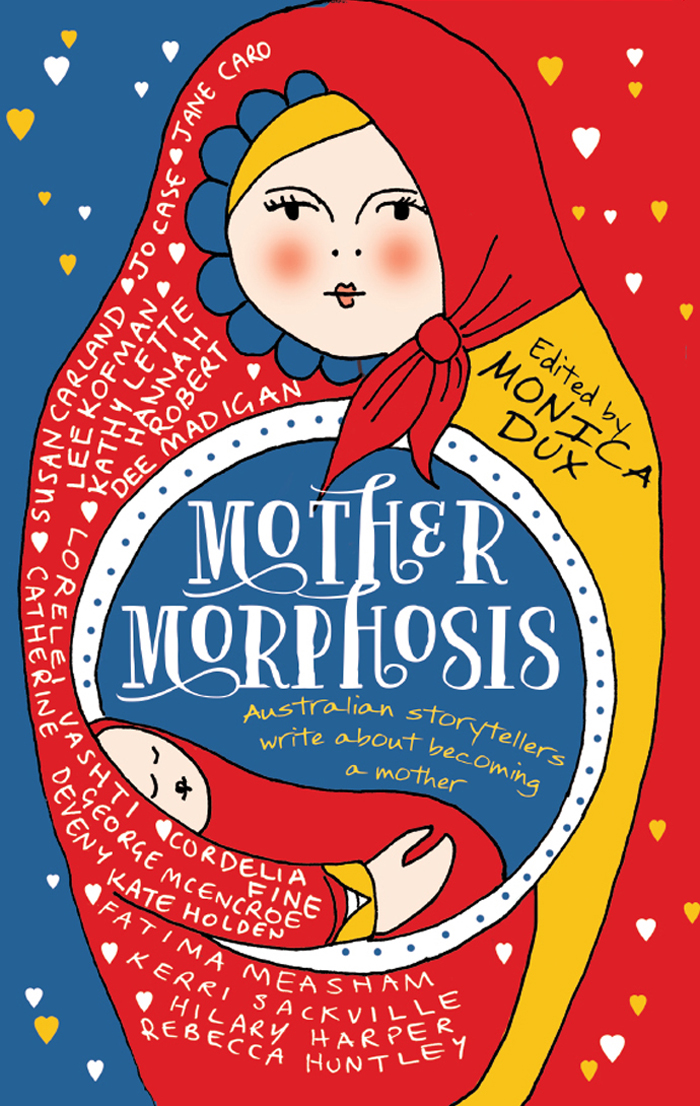

Cover design by Nada Backovic

Typeset by Megan Ellis

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

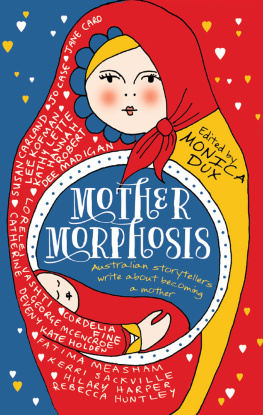

Mothermorphosis: Australian storytellers write about becoming a mother/editor: Monica Dux; contributors: Kate Holden, Kathy Lette, George McEncroe, Susan Carland, Jo Case, Lee Kofman, Lorelei Vashti, Hilary Harper, Hannah Robert, Catherine Deveny, Jane Caro, Rebecca Huntley, Fatima Measham, Cordelia Fine, Kerri Sackville, Dee Madigan.

9780522867831 (paperback)

9780522867848 (ebook)

MotherhoodAustralia.

MothersAustralia.

Mother and childAustralia.

306.8743

CONTENTS

Monica Dux

Kate Holden

Kathy Lette

Lorelei Vashti

Rebecca Huntley

George McEncroe

Fatima Measham

Jo Case

Hilary Harper

Cordelia Fine

Jane Caro

Hannah Robert

Susan Carland

Kerri Sackville

Catherine Deveny

Lee Kofman

Dee Madigan

MOTHERMORPHOSIS

MONICA DUX

Most Victorian-era photographs have a melancholy quality, but theres a peculiar sub-species that manages to be both grim and hilarious at the same time. These are, ostensibly, portraits of babies or small children, but take a closer look and you see another figure lurking behind the child, ludicrously disguised as a piece of furniture, or covered by a drape like an incompetent hide-and-seeker. As bizarre as these images first appear, it turns out that they have a mundane explanation. Early camera technology meant that subjects had to remain motionless while a photographic plate was exposed. Small kids are not known for their ability to sit still, so mums were often called upon to steady their children, while hiding themselves from the camera as best they could. This may solve the immediate mystery, but in another sense it makes these photos even weirderknowing that the lurkers are the childrens own mothers, yet someone went to such lengths to hide them, to subtract these women from an image of their own offspring.

Jump forward 150 years, and we find a world in which mothers have well and truly emerged from behind the figurative drape. Victorian mothers spent much of their lives behind domestic walls, excluded from public view, while modern mums move comparatively freely in the public realm. Indeed, the social pressure often flows the other way. From clingy maternity wear, proudly displaying our baby bumps, to the ubiquitous chat about yummy mummies and MILFs, we are no longer under pressure to hide, but to be ogled.

My first child was born on the cusp of the Facebook revolution, a heartbeat before we collectively decided that it was a good idea to share pictures of our dinner with everyone we know. Yet, when it came to baby announcements, the oversharing was already well under way, in the form of group emails, typically fired off to everyone on your contact list, often within minutes of the birth, and invariably featuring pictures of the newborn, being held by the freshly minted mother. In the months leading up to the birth of my first child I became rather obsessed with these emailed baby announcements or, more particularly, the photos that accompanied them. It seemed that the pictures I was receiving fell into two distinct categories, both of which troubled me, but for very different easons.

The first group, which Ill call Wrecks of the Hesperus, were candid images in which the new mother looked like something that had been washed up after a hard night spent at the bottom of a deep ocean trench. Voyeuristic and raw, looking at these pictures made me feel like I was invading someones privacy. The second type Ill call the Exultant Mothers. In these, the new mum looked fabulous, as if shed just jumped out of the shower after a bracing workout, then pulled a fresh new baby out of her gym bag and given it a big cuddle. If the Hesperus photos made me feel nervous, foreshadowing the physical pain that childbirth was going to involve, the Exultant Mums flat-out terrified me. For these photos spoke of a social ordeal that would be far tougher, and longer lasting than even the most protracted labour.

From the beatific Virgin Mary that you see in Renaissance paintings, to Carol Brady with her Buncha smiling embodiment of mid-twentieth-century domesticitythere have been many archetypal mothers in the course of history, multiple projections of a collectively held ideal. And as those Exultant Mother photographs accumulated in my inbox, I started to see them as representations of a new ideal. Relaxed and confident, casual yet sexy, informal but still stylish. An image that I desperately wanted to attain.

So, as my due date approached, along with the hospital bag that Id already packed (muesli bars, massage oil, maternity pads), I assembled another, secret bag. This one contained make-up, hair products, and a carefully chosen t-shirt that matched my eyes yet still looked like something I might have thrown on at a whim (for while modern motherhood might be yummy, it must also appear spontaneous and effortless). And that is how it came to be that I gave birth to a 4-kilo baby, endured an agonising twelve-hour labour in which I tore and required stitches then promptly did my hair, gave myself a quick make-over, handed a camera to my husband and posed for some carefully staged glamour shots, with my new baby as the featured accessory.

In the first photo Im not actually holding my newborn son, as doing so would have made me look all lumpy. Instead I placed him on the bed next to me, freeing me up to strike a more flattering, tummy-concealing pose. I lean forward over the child, like a tourist at the zoo, admiring an adorable, exotic creature that Ive stumbled upon. Cute, sure, but not something that I need to worry about, much less take home. In the second photo, the green shirt is off (Hello, Uncle Joe!), and Im breastfeeding my son. In reality, he was chewing on my nipples, not feeding from them, but I gritted my teeth and forced my most glowing smile, determined that no one would see my pain.

Looking at these photos now I can see that I would have been much better off hiding behind a hospital curtain, or disguising myself as a waiting-room chair. Or at least allowing myself to just be a Wreck, which is exactly how I felt. I still flush with embarrassment when I think about the staginess of those photos I sent out, their self-consciousness, yet Ive also forgiven myself for them. Because even as I struck my carefully calibrated poses, tucking in my tummy and baring some freshly lactating breast, I was really trying to hide, from what I imagined to be a collective, judgmental gaze, hoping that a bit of concealer, a touch of lip gloss and a designed shirt would prevent anyone from noticing that I had absolutely no idea what I was doing.