Acknowledgments

I will always be grateful to the people who appear in the book not only for all they taught me about Donegal but for their warmth, hospitality, friendship and terrific sense of fun. I am equally grateful to Mark Chamberlain, my first husband, for living in Donegal with me; without his warm exuberance and easily won friendships, Gathering Carrageen would be a very different book.

My thanks are also due to everyone at Sandstone Press, particularly Moira Forsyth, who with kindness, patience and an expert critical eye, guided me through the final stages of shaping the book. Thanks, too, to the K. Blundell Trust for a research grant, which helped prolong my stay in Ireland.

The support and encouragement of friends, family and colleagues during the long years of creating the book has been indispensible to me. In particular I would like to thank Myra Connell, who read each chapter as I wrote it and whose comments were always helpful and supportive, George and Brenda Dick, whose cottage in DonegaI I stayed in as a child, Caroline Shearing, their daughter, Ursula Monn, Barnaby Rogerson, Rose Baring, Richard Skinner, Ingrid Price-Gschssl, Kieran and Laurence Connell, Benji and Jacob Mitchell and of course, Adrian Mitchell friend, companion, and husband.

Finally, my thanks are due to Leon Rosselson for permission to quote from his wonderful song, Dont get married, girls, which is reproduced in full as an appendix.

Monica Connell grew up in Northern Ireland. She studied Sociology at London University followed by Social Anthropology at Oxford. Her first book, Against a Peacock Sky , an account of two years in a Nepalese village, was shortlisted for the Yorkshire Post Best First Work award and has been translated into two languages. More recently she trained as a photographer and published two illustrated books about Bristol contemporary culture, Flying High: New Circus in Bristol , and A Universal Passion: Music and Dance from Many Cultures . She currently lives in Andalucia.

Also by Monica Connell

Against a Peacock Sky

Flying High: New Circus in Bristol

A Universal Passion: Music and Dance from Many Cultures

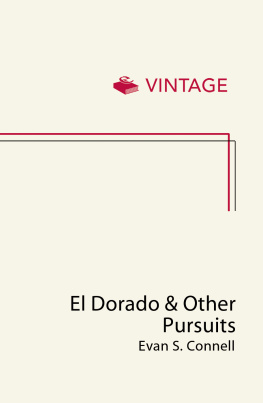

GATHERING CARRAGEEN

Monica Connell

First published in Great Britain

and the United States of America by

Sandstone Press Ltd

Dochcarty Road

Dingwall

Ross-shire

IV15 9UG

Scotland.

www.sandstonepress.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Copyright Monica Connell 2015

Editor: Moira Forsyth

The moral right of Monica Connell to be recognised as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act, 1988.

The publisher acknowledges support from Creative Scotland towards publication of this volume.

ISBN: 978-1-910124-46-8

ISBNe: 978-1-910124-47-5

Jacket design by Jason Anscomb

Ebook by Iolaire Typesetting, Newtonmore.

For my father, Kenneth Connell,

and my friends in Donegal,

with love and gratitude

All of us have a landscape of the soul, places whose contours and resonances are etched into us and haunt us. If we ever became ghosts, these are the places to which we would return. Colm Tobn, A Guest at the Feast.

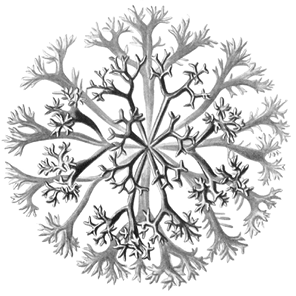

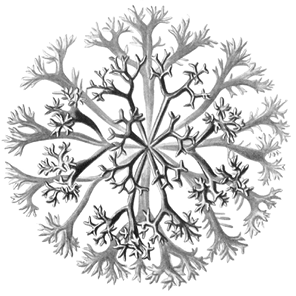

Carrageen ( Chrondus crispus ) is a short, tufted, reddish brown seaweed that grows abundantly on the rocky shores of the Atlantic. In Ireland it is also known as Irish moss, carrageen moss or, in Irish, carraign . It is used internationally in cosmetics and in the food and drinks industry as a stabiliser and emulsifier. In Ireland it is often boiled with milk to make a blancmange-like pudding called Irish moss: it is also traditionally believed to ease colds, flu and respiratory diseases.

CONTENTS

Authors Note

In order to protect the identity of the people in Donegal who so generously shared their lives with me I have not mentioned the name of the village where Mark and I lived. Similarly, with the exception of one or two people who chose to be recognized, I have used pseudonyms.

HOMELAND

My sister and I are standing at the waters edge, the frayed residue of waves foaming around our bare feet. Behind us dry sand is blowing horizontally across the beach; in front of us the full force of the Atlantic wind. We are leaning into it to stand upright. Our windcheater hoods are flapping, our black hair streaking across our faces, salty and wet. We are shouting to each other and laughing, but our words are drowned by the crashing of the breakers over the rocks and the roar of the wind.

When I was a child growing up in Belfast we often spent the summer holidays in Donegal. Usually we stayed in a traditional cottage that was rented long-term by some friends of my parents. It was in a small village of six houses, all thatched roofed except ours, which was slated, all clustered round the communal hand-pump, where in the mornings groups of women chatted as they filled their buckets and jerry cans. There was no running water or electricity in the village. For lighting we used paraffin lamps and candles. My mother cooked on a butane stove in the corner of the living room. There was no bathroom; we washed in basins filled from buckets, and there was a chemical toilet in the stone byre opposite the house, where the turf was stored, and various tools and sacks and cans of sheep dip and paint, which must have belonged to the owner.

Like most traditional Irish cottages this one had three rooms. The middle one was the living room with its stable door to the outside and its fireplace at one end with the old and blackened cast iron potato-pot suspended on a chain above it, and the turf basket, and the shelf above with its pebbles and shells and pieces of driftwood that our friends had collected on the beach. Behind the hearth, where it was warmed by the fire, was a bedroom where my sister and I slept on two divans. Our parents room was through a low door at the opposite end of the living room.

I remember days and days of rain; low cloud, drizzle, downpours that lasted all through one day and into the next. My sister and I put on windcheaters and took carrots and potatoes to the grey pony in the field behind the house, feeling her soft muzzle brushing our palms and breathing her damp pony smell. We played with the sheepdog puppy, Shep, and took her for walks on a length of string. And whatever the weather we went down to the beach: gathering shells, playing in the sand dunes, and (if our mother was there) swimming. Sometimes, after a swim, wed run all the way home in our towels and stand shivering by the fire as our mother made us hot chocolate or tomato soup out of a tin.

My father usually walked, all day. In the morning he made himself sandwiches (cheese and pickle, ham), which he packed in his knapsack with a flask of tea and a map, and set out in his walking boots and anorak, striding over the hills. He walked for miles, sometimes along the cliffs to a place Id only been to by car, a deserted fishing village at the end of a long un-tarred track: three stone houses, ruins, a rocky harbour lashed by the waves. No one lived there now, but there were some fishing boats upturned at the top of the pier and you could see the coloured floats of lobster pots bobbing about in the waves. I imagined the life they must have lived there, the loneliness, the danger when the boats put out to sea, and still now, as an adult, I picture my father sitting on the sheep-cropped grass on the cliff eating his sandwiches, silent, inconsequential amidst the shrieks of the seabirds, and the wind and the interminable breakers pounding the shore.