Im grateful to the Northern Ireland Department of Education, who financed my research in Nepal. For his help during the period of research, Im indebted to Gabriel Campbell, especially for the use of myths and quotations, without which the book would be infinitely less colourful. Thanks, too, to four Jumla schoolteachers: asi Bahdur Bua, Nara Bahdur Bua, Keb Mahat and Chandan Rokya, who patiently answered innumerable questions; and especially to Keb Mahat for his help with transcribing and translating stories and songs.

For their support during the writing of the book, Im indebted to many friends and relatives, but in particular to Hanna Connell; to Chris Sheppard for his determination to see the manuscript published; to Debbie Taylor and Myra Connell, who read several drafts of each story and whose criticism was both sensitive and thorough; and to Myra Connell and Mark Chamberlain for their belief in me, which has meant more than I can say.

Very special thanks are due to Dieter Klein, my agent, and to Tessa Strickland, former commissioning editor at Penguin. Thanks also to Clare Alexander, publishing director, and to Jennifer Munka, copy editor.

But my greatest debt is to the people of Talphi, especially the family with whom we lived; and to Peter Barker, who shared so many experiences with me, and whose photographs tell a similar story to my own in a very different way. Against a Peacock Sky is their book as much as mine.

F OR A LONG TIME Id expected to go alone to Nepal to do the fieldwork for my Ph.D. in social anthropology so, when Peter decided to come with me as photographer, research assistant, partner, I was delighted. The apprehension that Id felt about being on my own in a remote place now turned into the healthy anticipation of adventure: we started going to Nepli classes at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London; we scrutinised maps and guide books; we drew up lists and went shopping for things we would need.

At that time we knew roughly which part of the country wed go to, although not which particular village. The only real requirement was that it should be a Hindu, Nepli-speaking community. Apart from this, like most anthropologists I imagined being somewhere remote. I was romantic about fieldwork to the extent that I wanted to immerse myself in a traditional culture, one that was still relatively untainted by modern and Western influences. I was also keen to be somewhere that hadnt already been overrun by anthropologists I wanted a patch of my own.

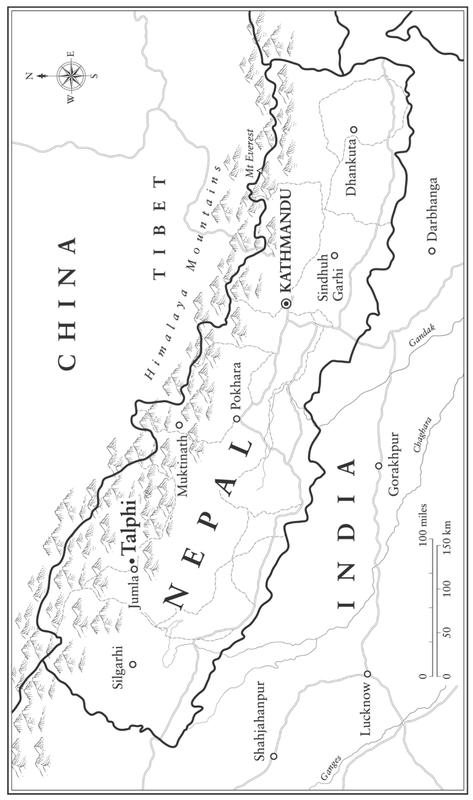

From the reading I had done, Jumla District, in the north-western Himalayan foothills, seemed to be the obvious choice. Jumla Bazaar, the District centre, is about ten days walk from the nearest motorable road, and although there has been a small airport with twice-weekly flights to and from Kathmandu since the 1960s, I reasoned that this would have little bearing on the lives of people one or two days walk away.

As to other anthropologists: from what I could gather there hadnt been many. The few who had worked there for any length of time had been researching high-caste Hindus Brahmans, Chhetris and hakuris. Reading their work, I came across numerous references to a group of people that no one had studied in depth the matawli Chhetris. or Untouchable communities). Without a doubt, this was where I wanted to go.

Although this question of the matawli Chhetri identity intrigued me, I didnt want to have an agenda. I was cynical enough, even in those early days, to be warned by the anthropologist who had spent ten years studying the language and culture of a tribe and then, on his first day in the field, found them speaking English, drinking Coca-Cola and dancing to American pop music on the radio. I wanted to go there, learn and document as much as possible, and then write my thesis on whatever seemed significant in whatever way appropriate.

Both in England and, later, in Kathmandu people warned us against working in Jumla. Their main reason was its relative inaccessibility. Although flights were regular in the spring and autumn, they stopped completely during the monsoon from the end of June until the beginning of October and were unpredictable during the winter when there was likely to be snow. In practical terms this meant that if there was an emergency, such as either of us being taken ill, we might have difficulty getting out. There were other reasons too. Many Kathmandu Neplis regarded Jumla as a backwater. They told us it was bitterly cold, underdeveloped, and that the people unused to foreigners would be suspicious, inhospitable and probably hostile.

We thought about this and about Jumla having been declared a food-deficit zone the previous year. We dreaded being an extra burden on scant resources. Nevertheless, we still wanted to go.

From the time we arrived in Kathmandu, it took four months for my research proposal to be approved by Tribhuvan University and for our visas to be subsequently granted. While we were waiting, I I would consult over and over during the early days of my fieldwork, when Jumla could just as well have been Mars.

We otherwise filled in the days by gathering things we would need. Some of these wed brought with us from England: a tape-recorder and blank tapes (for recording myths, songs and possibly interviews), a torch, batteries, a years supply of film, basic medical supplies, a few indispensable books. Others we collected in Kathmandu: down jackets, sleeping bags and walking boots (from the many second-hand trekking shops); cooking pots and pans; tea, coffee, spices, oil, candles any number of small things that cant be bought or are very expensive in Jumla Bazaar.

But it was really an impossible task, equipping ourselves for a place we knew nothing about. Some of the things that we took (our down jackets, pressure cooker, thermos flask) we were grateful for. On the whole, though, I felt that most luxuries created a bad atmosphere resentment on the part of the people we lived with, and guilt combined with fear of theft on ours. We never regretted not taking a radio; it would undoubtedly have attracted crowds of people (there were one or two radios in the village, but most of the time they were without batteries). Anyway, it seemed a rare privilege to be totally out of touch with the rest of the world for such long stretches of time.

We flew to Jumla in a fourteen-seater Twin Otter. Gaining height over Kathmandu City, we looked down on to streets of tall brick houses with strings of chillies hanging drying from the upper windows, temples with tiered pagoda roofs, the hustle and bustle of people and cars. Beyond the city was the green bowl of Kathmandu valley, rich and luxuriant throughout the year. Beyond that, barren brown hills, empty terraces from which the crops had already been harvested, houses clustered on hillsides in tiny cramped villages miles from anywhere. For a while we skirted the high mountain ranges of Annapurna and Daulaghiri, a huge uninhabited world of glistening snow and ice. Then, immediately, we dropped into the narrow valley that was Jumla.

We stayed in the small hotel in Jumla Bazaar. The owner Gaya Prasd, who sadly died during the course of our fieldwork, took us on an elaborate tour, pointing out the post office, the bank, the military barracks, the police station, the hospital, the unused family planning clinic and the tea shops; the Trade School run by the United Mission; the posts that had been erected to carry hydroelectricity and the trenches dug for drainage (neither project was completed during our time there). Afterwards, he took us to one of the Tibetan