Contents

Guide

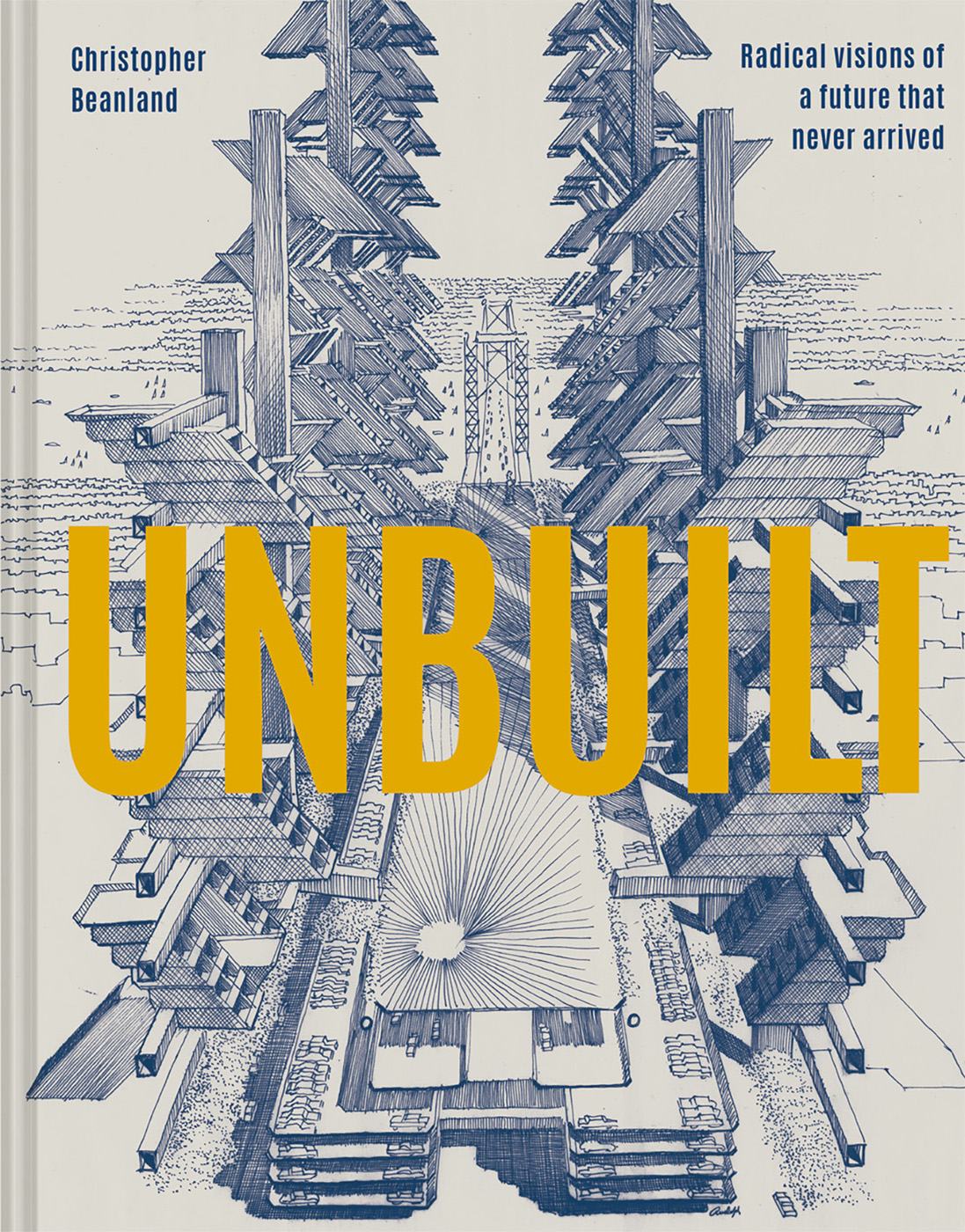

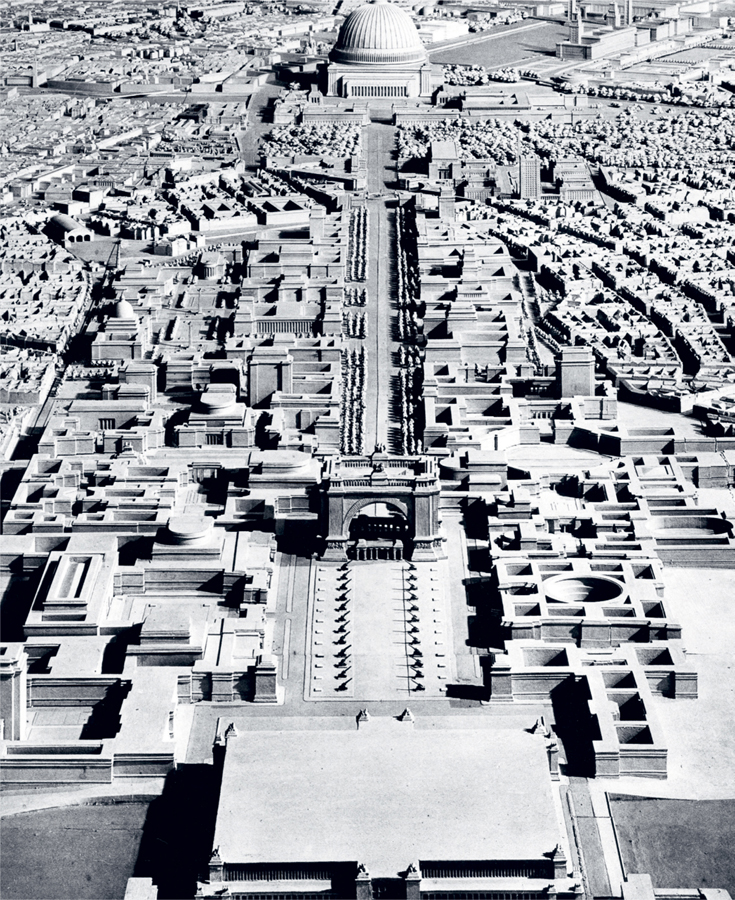

The NorthSouth Axis of Welthauptstadt Germania (see ).

CONTENTS

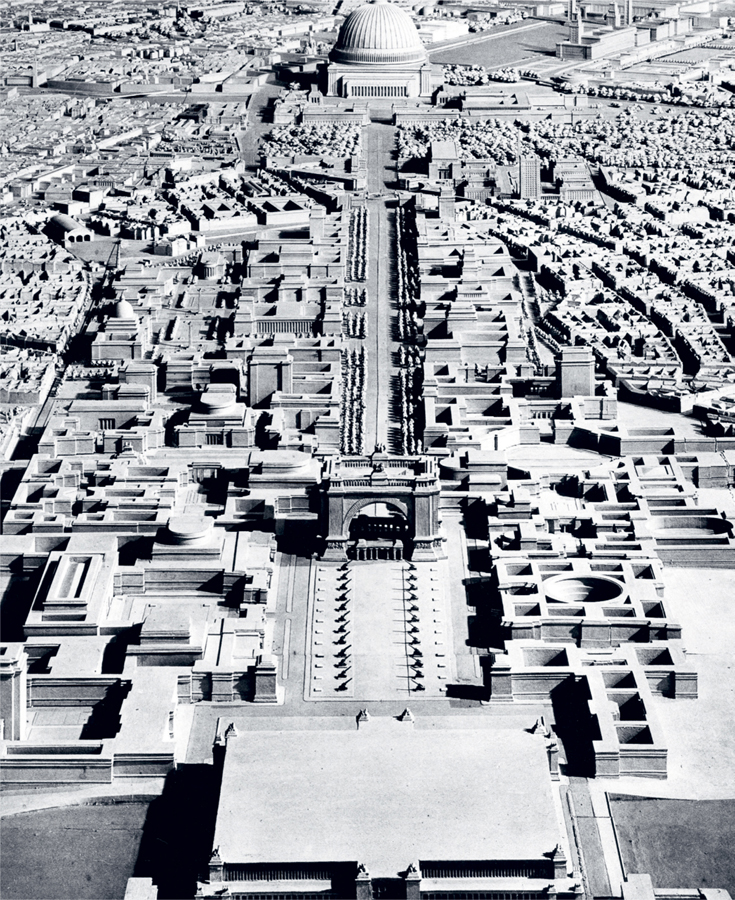

Rolling pavements: a vision for post-war Berlin (see ).

INTRODUCTION

Every human life is a series of failures. Every night we dream, every morning we plan. Everything is seemingly up for grabs. Everything we want, everything we crave. A whole world of everythings. Everything means nothing to me, sang Elliott Smith. One day we go up in smoke or down into the ground, having achieved a fraction of the things we set out to the ambitious and the creative will have done slightly more than the average.

An architect or a planners life is this model but supercharged many will never see a single design downloaded from brain to earth and remade in three dimensions, most will manage a few, some will give up altogether. Its very rare to be able to build a lot, rarer still for what you make to be what you want to make. Buy an architect a drink and listen to the reality, their reality: half of them draw up crap for money and are as disillusioned as a duck stuck in a car park. Most of whats on the books is the meat-and-potatoes stuff no book will ever discuss: the endless faceless flats, the big-box retail, the budget hotels.

The few lives we celebrate are akin to the few buildings and plans we celebrate the rest is a mediocre mess, just a lot of stuff in the middle. Every life is both ordinary and extraordinary, mulls Logan Mountstuart in William Boyds Any Human Heart, a novel that distils the elemental essence of what life actually means. Mountstuart keeps dreaming, keeps trying; a lesson for us. Each loss, each failure, is just a necessary part of life. A horrible thought: could this be the pattern of my life ahead? Every ambition thwarted, every dream stillborn? To be in a position of being able to dream, to try, to express ones creativity, is a privilege, particularly a Western middle-class privilege though not a privilege thats particularly well paid until one clambers to the top of the greasy pole brickies legendarily out-earn junior architects. Everyone out-earns writers. What do we want from a society? Evidently people good with their hands, celebrities, estate agents and yet more hedge-fund managers.

A little less conversation, a little more action, sang Elvis. It could be the architects theme song. For so much is a discussion, a proposal, an attempt. Even when the ts have been crossed and the is have been dotted and the foundations have been sunk its no guarantee that the project will be finished. Look at the things that never got completed, like Watkins Tower in Wembley or the Palace of the Soviets in Moscow.

Most ideas dont get this far. Maybe 90 per cent of what architects do is some level of theorizing; 10 per cent involves donning a hard hat. The hard hat is so seldom worn that the on-site brigade can easily spot how uneasily the yellow plastic crown sits atop the pate. Thats the architect we could just look for the one person wearing all black instead (good luck trying that ruse in Berlin though).

Architecture is an ideas business, a words and drawings business, a thought business even. The attempt is to improve. To improve one has to innovate. Innovation doesnt sit well though, least of all in Britain where the Second Industrial Revolution petered out decades ago, where an entire manufacturing industry is put in museums and where the modernist behemoths of the 1950s to the 1970s have mostly been knocked down. On Sunday afternoons we drive the car to famous buildings from well before that fecund period and admire them, then we drink tea and eat scones and reflect on what weve seen while we read recipes and interviews and blind-date aftermaths in the supplements. Maybe we should be visiting the archives instead and looking at infamous sketches of buildings and admiring them and wondering why they exist on paper rather than on the skyline. We fetishize whats been done, we worry about whats yet to be done and we ignore whats not done. Innovation comes from the latter two.

Turning theory into built reality is a fag, yet its not as complex as Robert Hughess assumption about art: that the artist turns feeling into meaning. That is alchemy. Architecture is craft far from easy, but with a set of rules to follow, parameters, guides, regulations and a huge amount of (as with films and publishing thanks, editors!) unrecognized teamwork alongside the auteur. Anyone who labours under the misapprehension that that one starchitect designed that new museum you enjoyed fleetingly is barking up the wrong tree, just as the idea that I am the sole person involved in getting this book into your hands is meretricious. An artist has a patron but doesnt have to take as much shit from them as an architect has to take from a client. But then an artist is a genius (well ) and an architect a realist (well, mostly). When we talk about failed architecture, how often is it the client who has lost faith, cut corners, slashed budgets, failed to get buy-in from stakeholders to get things moving? Other forces can prevent the reality happening too: community action which grew exponentially throughout the twentieth century, like environmental protest, locals saying no. Its a valid point: no one wants things done to them. If a road is going to be ploughed through your park, or your favourite community centre is going to be bulldozed, youve every right to be pissed off about it. Add in planning controls, changes of political regime, changes of priorities, money running out, war breaking out, architects burning out, um pandemics.

Architecture happens at a grandmotherly pace: its no wonder things slip through the cracks when the project youre designing today may not top out for 10 years; much can change in the intervening period. Its a wonder anything gets done.

If were discussing the unbuilt, we also need to remind ourselves that just because a building is built, its story isnt over. When is a building finished? It is no more settled than we could say a human is finished when it arrives. Throughout the life of human or building many changes will happen improvements, ill-thought-out renovations, degradations.

Architecture has sought to improve the world (mostly ignore todays rampant neo-liberal need for development dosh for a second). Theoreticians wanted something better. Theyve not always been listened to. Throughout history, from the first time we lined stones up, plans have been concocted and although in this book we concentrate on the twentieth century, because the richest ideas of all come from that era, there are also instructive lessons from before the 1900s. Antonio di Pietro Averlino, or Filarete to his mates down the pub in Florence, was always on about his idealized city of Sforzinda in the 1450s. Moving beyond mere architecture, beyond one building towards building many, we see a long lineage of supersized visions that challenged the very way life was conducted. People have consistently sought to change the way other people behave. That process speeded up (as did every other facet of life) in the twentieth century. Example: the three-dimensional city idea that permeated like salad cream through Mothers Pride bread in the post-war world. The idea of putting pedestrians up above cars became a secular religion. The pedestrians in question never fully bought in to these doctrinal decrees, as the desire lines and vaulted barriers and windswept walkways attested to.