CONTENTS

by Martin Filler

INTRODUCTION

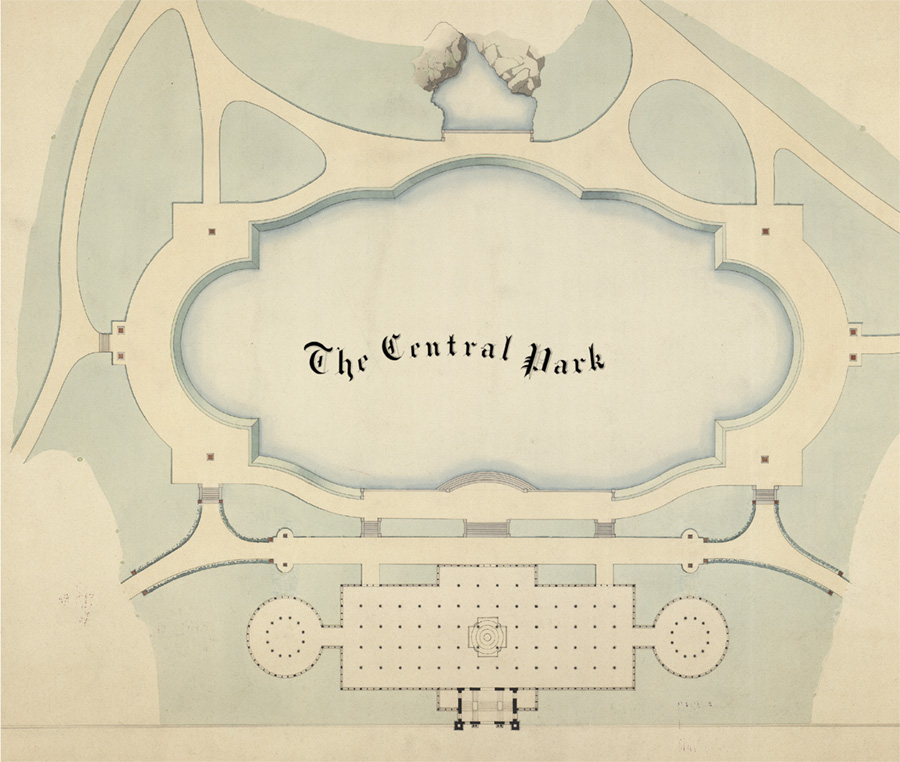

The Greatest Single Work of Art in the City of New York

CHAPTER 1

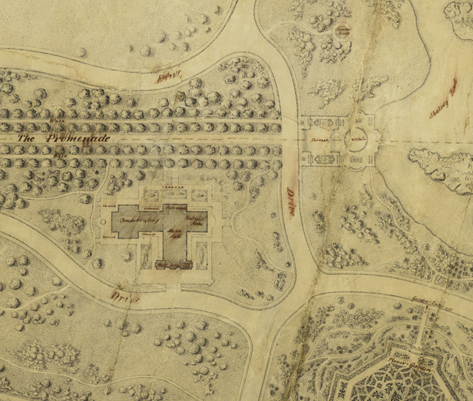

The Genius of the Plan

CHAPTER 2

The South

CHAPTER 3

The West

CHAPTER 4

The North

CHAPTER 5

The East

CHAPTER 6

The Heart of It All

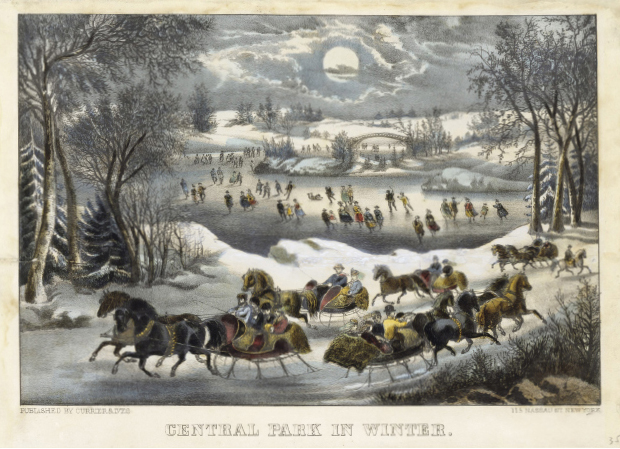

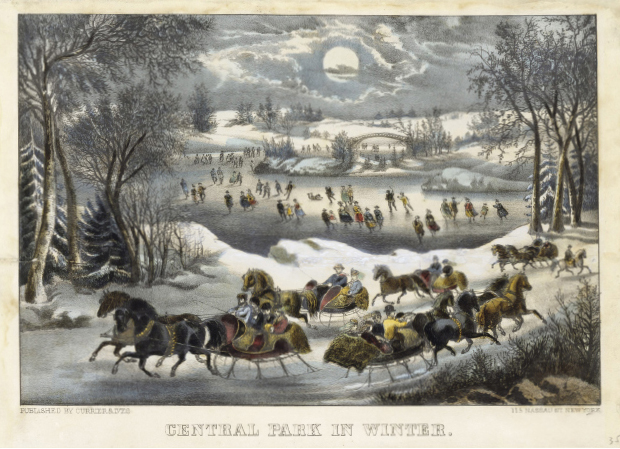

Central Park in Winter. Hand-colored lithograph by Currier & Ives, c. 1870s.

FOREWORD

Central Park, the creation of a partnership between the visionary Frederick Law Olmsted and the architect Calvert Vaux, was the project that secured their high place in the history of architecture and urbanism. The triumphant outcome of that unprecedented commission, the first phase of which opened to the public in 1858, was widely publicized (including popular color lithographs by Nathaniel Currier and James Merritt Ives that celebrated the seasonal pleasures of Central Park, from spring promenades and summer boating to autumn carriage rides and winter ice skating), and led to Olmsted and Vaux being asked to design several other urban oasesmost notably Brooklyns superb Prospect Park of 1865-1873. After they ended their collaboration, in 1872, Olmsted went on to become Americas foremost landscape designer, and his large firm established modern standards for an old discipline that had never before been so thoroughly professionalized or so democratic in its public applications.

From Central Park onward, what had long been the exclusive privilege of a landowning aristocracyopen access to verdant acres that offered restorative contact with naturebecame an amenity to be enjoyed by all city dwellers in common. Few accomplishments of the reform movements that arose during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries surpassed the social, physical, and psychological benefits provided by Olmsted and Vauxs revolutionary breakthrough, which has improved the daily lives of millions over the past 160 years.

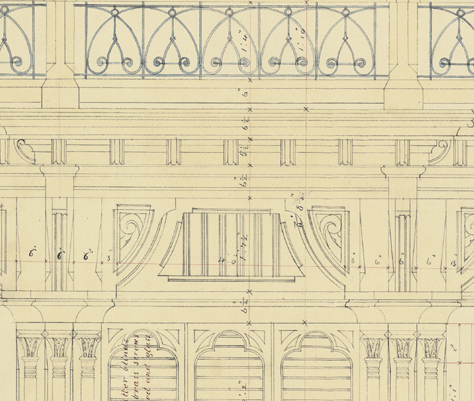

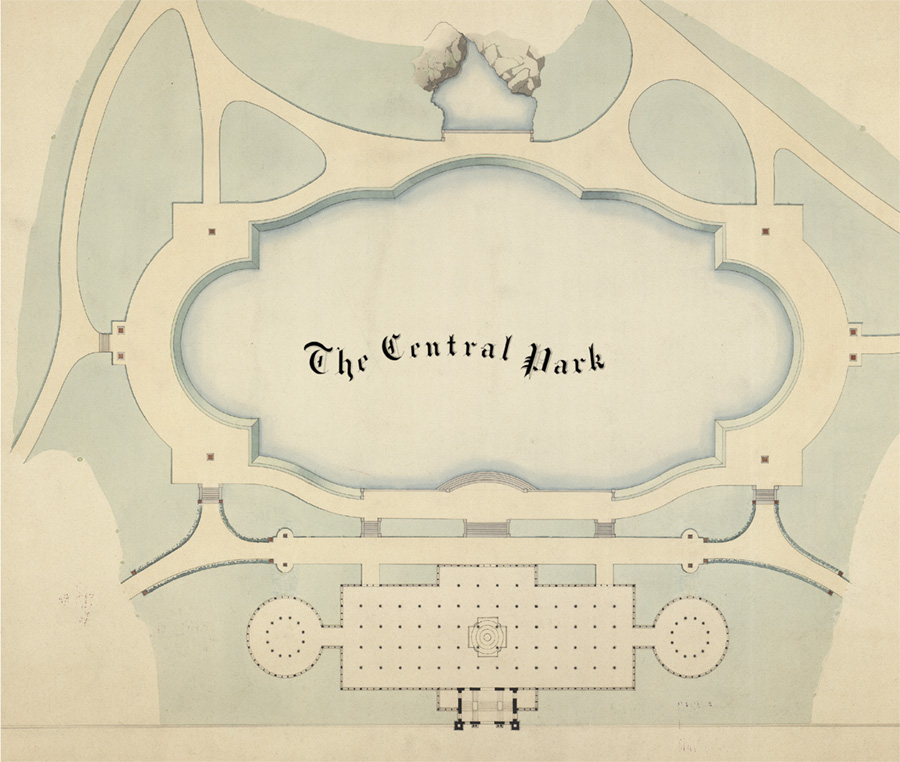

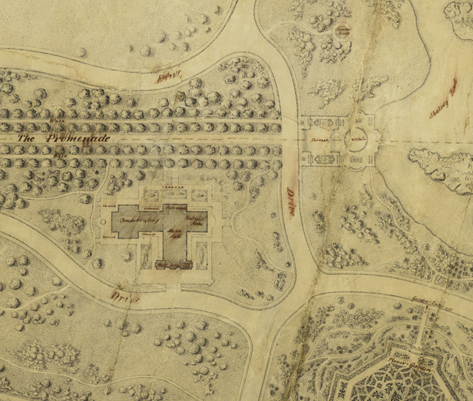

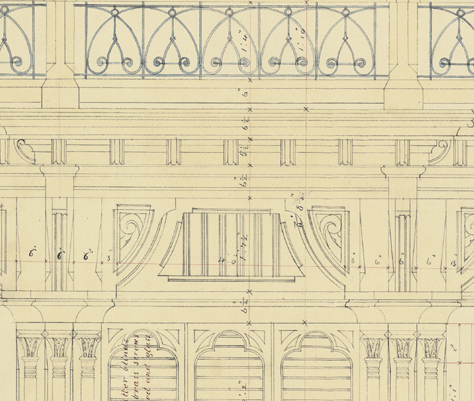

Central Park is not just the greatest example of its kind in the United States but, more remarkably, the first. Readers of this book, which is filled with detailed architectural designs for structures in the park, will immediately grasp the essential nature of Vauxs contribution; Olmsteds is worth underscoring at the outset. The self-taught polymath was the Proteus of nineteenth-century American civic culture: pioneering practitioner of innovative scientific farming methods; cofounder of the still-extant political and literary magazine The Nation; author of the sharpest first-person account we have of life in the American South immediately before the Civil War; reformer of military health care in the U.S. Army during that conflict; and champion of nature conservation policies that led to the creation of our National Park Service. The design of Central Park exemplified the characteristic that enabled Olmsteds mastery of so many diverse fields, which in computer science has been called predictive vision, a term that perfectly describes his uncanny creative foresight. Unquestionably, an ability to project what a landscape design will look like in three dimensions at full maturity is a useful talent, but a rare one. (This is why the eighteenth-century British landscape designer Humphry Repton devised illustrated books that included foldout vistas with movable colored overlays to show before and after versions of his proposals and explain his ideas to patronsa foretaste of the presentation boards with which Olmsted and Vaux persuaded the parks Board of Commissioners to adopt their Greensward plan of 1858 as the winning entry in the parks design competition.) Few laypeople can apprehend the outcome of such transformations, let alone fathom that Central Park, a seeming vestige of primeval nature somehow miraculously preserved, is a wholly manmade invention.

Before Olmsted diedat eighty-one, a great age in 1903his certainty about how the Greensward plan would ultimately turn out was vindicated as its trees reached their full height after four decades and his naturalistic compositions took on an abundant appearance much like the Central Park we know today (rather than dotted with the feathery saplings depicted by Currier and Ives early on.) During that same timespan the population of Manhattan grew no less vigorously, from 813,000 in 1860 to 1,850,000 in 1900, a rise of more than a million inhabitants. What began as wasteland reclamation on the outer fringes of the populated city had by the end of the century turned into the proverbial green lungs of New York.

By the turn of the twentieth century Central Park was hemmed in on all four sides, much in the same way that Manhattans postmillennial wonder, the High Line, has stimulated real estate development on its periphery. In both instances, although more than a century apart, ever-taller buildings formed a veritable palisade enclosing each park, as the citys economy prospered and apartment houses were erected to the maximum legal height in order to take advantage of a rare respite from increasing urban density.

Central Parks enduring hold on the public imagination is reflected in its recurrent presence in popular entertainment, and especially the movies of the Golden Age of Hollywood, which defined an idealized cultural landscape for all Americans. There was Gold Diggers of 1933 (which featured Pettin in the Park, a bizarrely sexualized production number choreographed by Busby Berkeley) and Born to Dance (1936), in which James Stewart serenades Eleanor Powell with Cole Porters haunting ballad Easy to Love. Even more compelling was Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisses Dancing in the Dark sequence in The Band Wagon (1953), a pinnacle of midcentury dance. Often Central Park was portrayed as almost a character in itself, a place of pure romantic enchantment where a couple in love could find themselves together but alone at the very heart of our greatest metropolis.

These three musical numbers were all filmed at ground level, and indeed on studio sound stages rather than in the real thing. However, Central Park has been used as an on-site location for a long list of other films, from the silent

Next page