ALSO BY ELIZABETH BARLOW ROGERS

Green Metropolis: The Extraordinary Landscapes of New York City as Nature, History, and Design

The Forests and Wetlands of New York City

Frederick Law Olmsteds New York

The Central Park Book

Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan

Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History

Romantic Gardens: Nature, Art, and Landscape Design

Writing the Garden: A Literary Conversation Across Two Centuries

Learning Las Vegas: Portrait of a Northern New Mexican Place

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2018 by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Rogers, Elizabeth Barlow, [date] author.

Title: Saving Central Park : a history and a memoir / by Elizabeth Barlow Rogers.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, [2018] | A Borzoi book. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017023487 (print) | LCCN 2017035973 (ebook) | ISBN 9781524733551 (print) | ISBN 9781524733568 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Central Park (New York, N.Y.)History. | Rogers, Elizabeth

Barlow, [date] | Central Park Conservancy (New York, N.Y.)History. |

Central Park Conservancy (New York, N.Y.)Biography. |

ConservationistsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. | Landscape

architectsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. | Women

conservationistsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. | Women landscape

architectsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. | New York (N.Y.).

Department of Parks and RecreationOfficials and employeesBiography.

Classification: LCC F 128.65. C 3 (ebook) | LCC F128 .. C3 R642 2018 (print) |

DDC 333.78/3092 [ B ]dc

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017023487

Ebook ISBN9781524733568

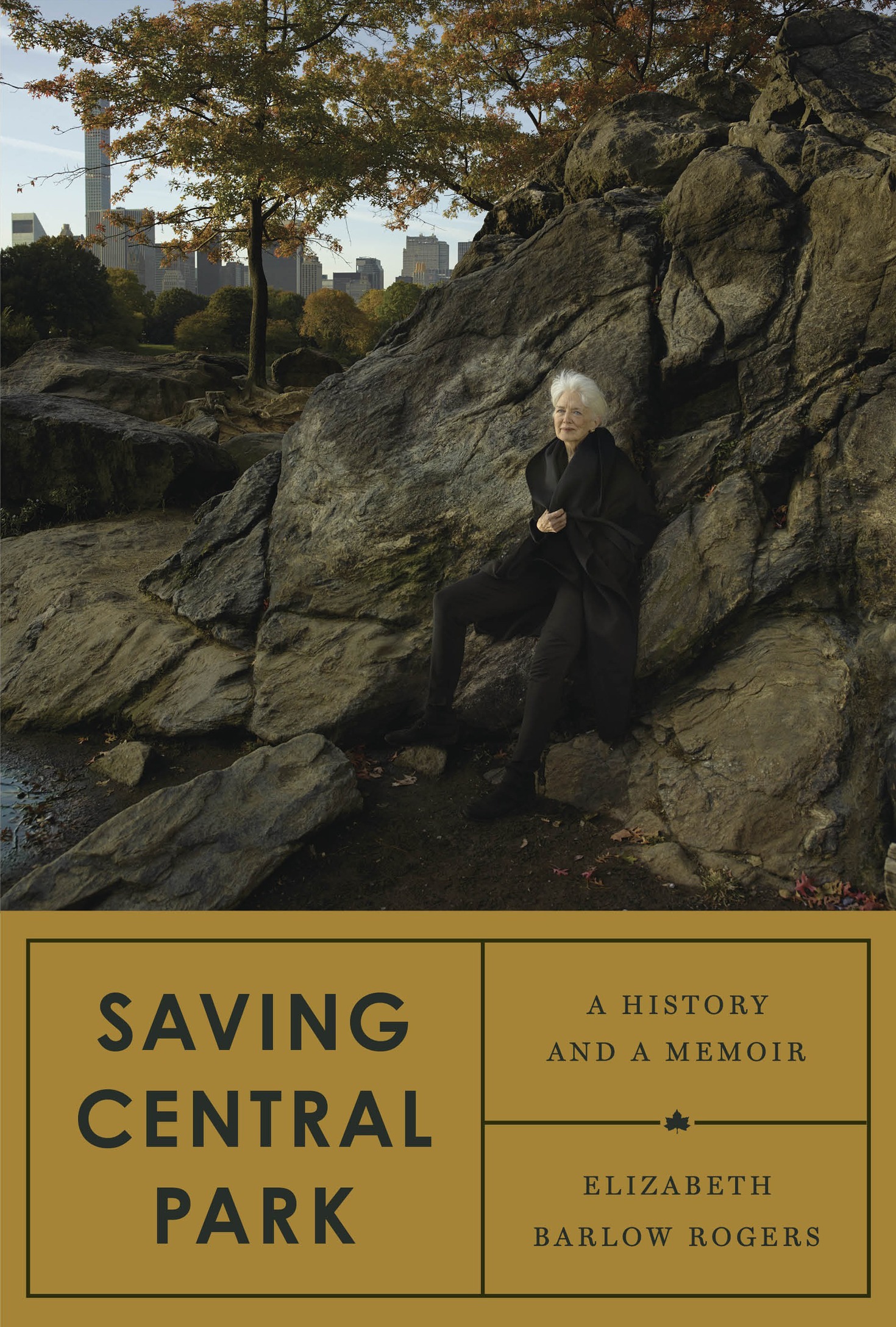

Cover photograph by Annie Leibovitz / Vanity Fair / Trunk Archive

Cover design by Janet Hansen

v5.2

ep

For the men and women who built and rebuilt Central Park

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Implausible Ideal

The memoir of a financially secure author who came of age in the 1950s in an atmosphere of privilege that included parental love, a comfortable home, educational advantages, conscientious moral instruction, and bodily health is not likely to be as compelling as ones written by women and men whose autobiographical narratives grow out of less advantageous and more unconventional circumstances. Those books written by authors who have participated in war or been its victims have history as background interest. Ones by people who have fought mental or physical affliction, social injustice, or racial discrimination inspire sympathy. Explorers into the unknown and adventurous travelers to exotic locales have ready-made dramatic material at their command. Memoirs by politicians and celebrities are sure to sell.

In this light, my life story would not be particularly interesting except for one improbable fact: at a time when Central Park was on the brink of collapse, I became, through a combination of zeal and luck, the leader of the cause to save it from destruction. Because what was being savedand still must be protectedis both a masterpiece of landscape design and a great democratic institution, what follows is as much a history of how the park itself was built and altered during successive eras as it is a chronicle of my role in its renaissance.

Becoming the torchbearer for this cause was even more improbable given my gender, generation, and class. For middle-class girls like me growing up in the years immediately following the Second World War, there was a stigma attached to being a salaried professional woman. At that time the term career girl was a mild pejorative, and the notion of becoming a female lawyer, doctor, or business executive was virtually unknown. Poor Mrs. Brown, my mother told me when I was around nine years old, she has to workadding that if I found myself in such a position, my options were restricted to the jobs of nurse or schoolteacher, as in Mrs. Browns case. Like me, most of my classmates at Saint Marys Hall, the San Antonio private girls school I attended from fifth through twelfth grade, were expected to go east to college for two years before transferring to the University of Texas, joining a sorority, making their debut into society, finding Mr. Right, becoming engaged, marrying, and raising a family.

My decision not to leave Wellesley College after my sophomore year, to obtain a masters degree in city planning from Yale, and to use my skills as a writer about nature, open space preservation, and the history of landscape design was my unwitting springboard to an unusual and immensely satisfying self-created career. What the reader will observe in this book, therefore, is the trajectory of a life lived on the cusp of societal change, in which I have been gratefully buoyed up by the womens movement while at the same time benefiting from some of the positive values conferred by an older ethos of middle-class womanhood without being stereotypically trapped by convention.

It is not an exaggeration to say that Wellesley changed my life by enlarging my sense of self in relation to the world around me. Since it is an all-womens institution, Wellesley implicitly accorded its students the status of honorary men in the classroom, if not in the dormitory where weekend dating was still governed by strict parietal rules. But after graduation a girls (we twenty-one-year-olds werent yet referred to as women) diploma did not carry with it the assumption that she was prepared for work outside the home. No matter how brainy and self-sufficient we might have felt ourselves to be with our good educations and leadership skills, very few of my classmates opted to go to graduate school and earn a PhD as opposed to an MRS. The salutation Ms. had, of course, not come into common usage, and none of us dreamed of retaining our maiden surnames after marriage. Nevertheless, I thought it was going a bit too far when our Wellesley commencement speaker exhorted us to consider using our liberal arts educations to reanimate our minds and pursue the intellectual interests we had developed at Wellesley after we had raised our children and sent them off to college.

Here a distinction should be made between my professional life and the model for todays successful Wellesley woman, whose taken-for-granted career ambition has, if not completely shattered the proverbial glass ceiling, at least created some notable cracks. In my case, it might be more accurate to say that I wormed my way through the soil of a green rooftop. Being who I am, Im glad my somewhat novel vocation didnt land me in a chair at the head of the table in a boardroom or on the political campaign trail. Instead, I found myself looking up at the blue sky, uncertain if the clouds would turn to rain but at least with a pilots license that would allow me to fly.

With no aviation instructions, I still had to figure out how to get off the ground. My ascent, however, was actually made easier by the seemingly innocuous nature of my job. After all, nurturing the park was not unlike nursing a patient, and gardening, like elementary school teaching, has traditionally been considered a female activity. Moreover, because what I was doing seemed quixotic and nobody really had any idea whether my mission was plausible, gender was irrelevant and questioning my competence to do my job was simply a wait-and-see matter. That would only come later when the Central Park Conservancy had become a conspicuous institution within the life of New York City with the capability of raising serious money. By then I knew that I had supplemented my original vision to save Central Park with sufficient leadership and management skills to make any presumption of my inability to do my job insulting.