IMAGES

of America

MACARTHUR

PARK

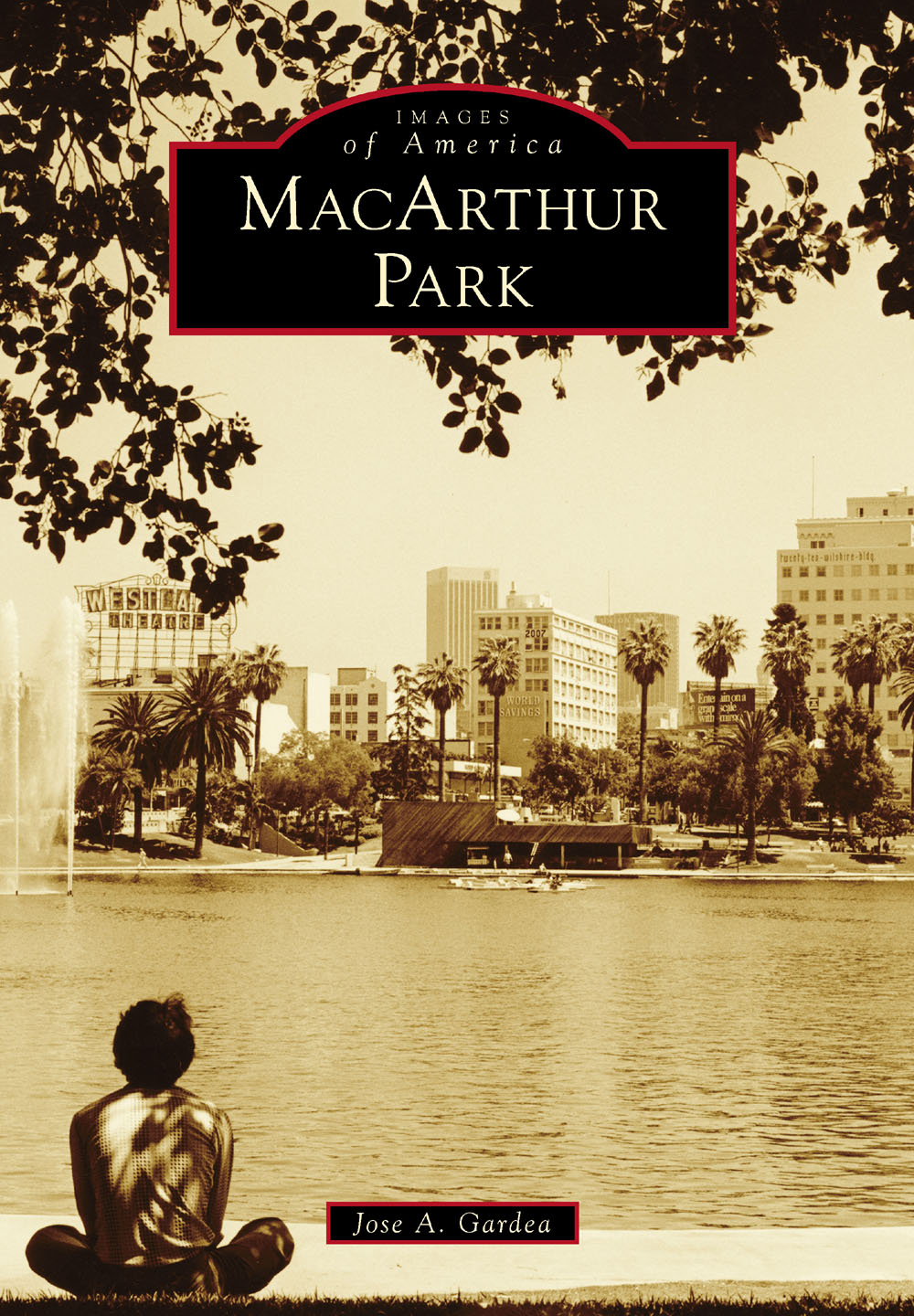

ON THE COVER: A young person finds a moment of respite and contemplation while sitting in MacArthur Park, one of Los Angeles oldest, imminently attractive, and most democratic parks. MacArthur Park evolved alongside its home city as Los Angeles was becoming the modern metropolis it is today. The park has experienced multiple physical transformations and a name change, but it has never lost its intent and purpose to serve the millions of souls that call Los Angeles home. (Courtesy of the Los Angeles Public Library Photo Collection.)

IMAGES

of America

MACARTHUR

PARK

Jose A. Gardea

Copyright 2015 by Jose A. Gardea

ISBN 978-1-4671-3345-6

Ebook ISBN 9781439651742

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015939110

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

For my wife, Susanaone more book for our bookcase; and

my sons, Zacharias and Sebastianview the world with wide

eyes one book at a time, it is a beautiful responsibility.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

MacArthur Park is a unique place in Los Angeles. This accolade is only possible because unique people have always appreciated the parks role in nurturing community and building our city. It is well documented since the inception of Westlake Park that this public space has had many champions fighting for causes and resources that are critical to the preservation and restoration of this great park. It would be a mistake on my part to try to name these champions across the generations of time who have accepted the challenge of advocating for MacArthur Park. It is indeed a long list. But, believe me, they have all left their marks in the park. Perhaps this subject can be articulated at a different time and under a different format. For now, however, thank you all.

A thank-you goes to those individuals and organizations that allowed me the use of the archival photographs: the Los Angeles City Archives (Michael Holland and Todd Gaydowski), the Los Angeles Public Library, the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County (John Cahoon), the USC Digital Collection, the Los Angeles Times photograph collection, the Watson Family Photography Archives (thank you, Dan Watson), Karen Mack from LA Commons, Joe Colleti from IURD, and the good folks from CicLAvia.

I want to thank Liz Hirsch and her fellow board members from the Levitt Pavilion for their support and encouragement. Keep the music playing at the park!

Many of the modern-day photographs in this book were taken by the incredible Meeno Peluce (Meeno), a Los Angelesbased photographer who always amazes me with his skills and talent. Thank you for your poetic perspective of the park.

A thank-you goes to the editors at Arcadia Publishing for their direction and patience. I truly appreciated the journey.

One final thank-you goes to the millions of immigrants from across the world who have called the Westlake neighborhood home and MacArthur Park their public space to recreate and gather. In particular, I want to thank Eva Gardea, my mother, for the courage to come to a new country and arriving to this neighborhood. Her story is shared by so many, a story of sacrifice and hope. May the millions who will come in the future continue to see Westlake and MacArthur Park as portals for opportunity and growth.

INTRODUCTION

Los Angeles is a big city, but MacArthur Park makes it a democratic place. I am reminded of this every time I sit in the park. I remind myself that I am sitting in the middle of one of the most crowded neighborhoods in the country, where hundreds of thousands of immigrant souls, primarily from Mexico and Central America, live in high-rise buildings that once reached elegantly for the clear, blue sky, but today strain under years of deafening hardship and trembling turmoil.

I remind myself that beyond the transparent borders of this neighborhood expands a metropolis of 13 million dreamers, searchers, and workers. This is a city that, since its founding along the Rio de Nuestra Seora la Reina de Los ngeles de Porcincula, has been hungry to grow its territorial boundaries and search for precious water to accommodate its collective thirst.

Westlake Park, as MacArthur Park was originally called, fulfilled both realities. The creation of the park in 1886 solidified the western edge of a dusty town already searching for its manifest destiny to the Pacific Ocean. The early city surveyors established the citys western boundary a few hundred yards west of the lands that would become Westlake Park, an area unclaimed by the local ranchos and not known for its physical attractiveness. But the sea was still many miles away, and local property owners were eager to prosper.

Los Angeles was indeed dusty, both because of its desertlike geography and the constant threat of drought in this part of California during the late 19th century. As a result, the capture and storage of water became a matter of survival for the emerging city, an assignment that the new public park and reservoir was given.

Westlake Park and the expanse between the new park and the original city border to the east quickly became points of pride for local stakeholders and ambitious elected officials. The new park was photogenic, and the new city needed a relief valve for its residents to gather, breath, and recreate. Thus, the peoples park was born.

For much of the 20th century, Westlake/MacArthur Park served as a mirror for the entire city of Los Angeles. The park and the neighborhood around it were a microcosm of the infrastructure, social, transportation, and economic forces that created the second-largest city in the country. As the citys watershed and requisite engineering challenges needed to better manage its water increased, so did the importance of the park as a catchment area. With the sea many miles to the west of the original pueblo, the city grew in that fateful direction. The neighborhood around Westlake Park experienced the first critical levels of population density as the decades passed. Many observers will argue that the city was unprepared, or perhaps unwilling, to adequately manage the population explosion that occurred in this neighborhood as the postwar decades progressed. Clearly, the lack of strategic thought and action on this issue heavily impacted the park itself. Although the park always patiently endured periods of municipal neglect, the strain on its resources created an environment of fear and lawlessnessa phase the park is still trying to recover from.

When cars and people needed to move to the west side of the city to shop or work, the park sacrificed its green space for this objective to be achieved. On the economic front, as the citys workforce went from a base of makers to a base of servers, the Westlake neighborhood became home to the largest group of immigrants that served our food and cleaned our homes and offices.

During this period, the park experienced two distinct and significant traumas. Two major construction projects (the Wilshire Viaduct and the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authoritys Red Line subway) permanently scarred the design and biological ecosystem of the park, and the second injury was the renaming of the park after Gen. Douglas MacArthur, an act that on its own was not fatal to the park. However, the injury was inflicted on the local community, which was unhappy with the name change.

Next page