The history of Yellowstone National Park is storied, extensive, and complex. Crafting a brief narrative of the famed parks natural and human history is a daunting endeavor. I am deeply indebted to two individuals who helped me navigate the deep and wide terrain.

Lee H. Whittlesey, now retired, was Yellowstones fourth National Park Service historian. The dean of Yellowstone historians, he is a prolific author of the parks history. Lee read my manuscript, pointed out deficiencies, and set me straight on a number of occasionsencouraging me all along the way.

Elizabeth A. Watry, an outstanding western historian and Yellowstone historian, as well as a prolific author, also read my manuscript, graciously providing clarity on a variety of subject matters. She also encouraged me to include opening quotes for each chapter.

For their assistance with identifying and obtaining images, I am indebted to Larry Lancaster and Jack Davis, avid collectors of, and deeply knowledgeable about, historical Yellowstone images, postcards, and posters.

In addition, I am most grateful for the excellent work of the Globe Pequot editorial and production team of Rick Rinehart, Meredith Dias, and Joanna Beyer.

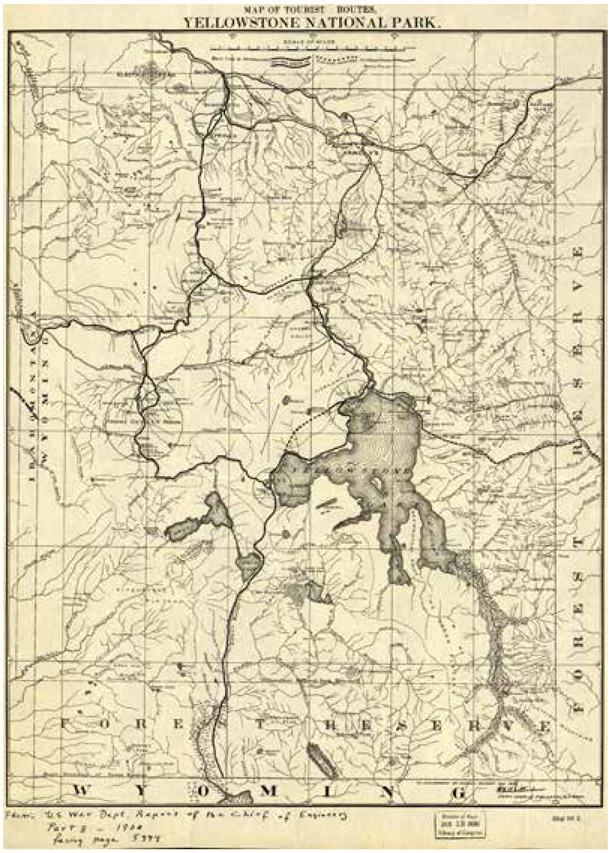

This map of Yellowstone National Park, produced by the US War Department while the park was under the administration of the US Army, depicts tourist routes in the year 1900. Note that todays Tower-Roosevelt Junction area is labeled as Yancys, a misspelling of John Yancey, proprietor of an early hotel (18821906) near the junction that failed to withstand the test of time. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, UNITED STATES WAR DEPARTMENT, OFFICE OF THE CHIEF OF ENGINEERS. G4262.Y4 1900 .U5 TIL.

[O]ur greatest national heritage is nature itself, with all its complexity and its abundance of life...

GEORGE M. WRIGHT, NATIONAL PARK SERVICE BIOLOGIST, 1933

IN THE HEART OF WINTER ATOP A HIGH MOUNTAIN PLATEAU BATHED IN scenic beauty, a battle for life unfolds. The days are short and perilous, the nights long and unforgiving.

It is the season of the wolf.

For months the bitter cold remains, with snow and ice blanketing the Yellowstone plateau. Vegetation, dormant and often buried, offers only scant nutrition for ungulates. For all animals, fat is the currency of survival.

While bears safely shelter in hibernation and live off the fat stored in their bodies, elk remain upon the landscape, exposed. Winter is their ultimate test. Their body fat diminishing from day to day, that which sustains them during the harshest of seasons is also life-giving food for wolves.

Ever vigilant, wolf packs stalk the most vulnerable of elk, the species critical to their winter survival. A wolf packs proximity to an elk herd causes the ungulates to expend valuable energy in maintaining distance from their hunters. Shadowing the herd, the carnivorous canids are patient predators.

Their bodies weary of constant movement, a herd of elk allows a wolf pack to draw too close. Sensing opportunity, the wolf pack charges, setting the already weakened herd into slow-moving flight through deep snow. Spread out, the wolves on a run approach from multiple directions, disorienting the fleeing herd. Within moments, one young elk, smaller and weaker than the others, falls slightly behind.

In Yellowstones Lamar Valley, a coyote trots through winters snow. COPYRIGHT BRUCE GOURLEY

Pivoting, the individual wolves from differing directions charge hard through the snow, confusing their prey. From behind, the first wolf lunges and grabs one of the elks hind legs in its powerful jaws, bringing the animal to a standstill. Within seconds, off to the side a second wolf hurls itself upon the hapless animal, burying its teeth deep into the neck of the wounded elk. In another moment, the remaining members of the pack arrive. Each grasping a part of the elk in their jaws, they pull the animal to the ground.

Furious in their hunger, the wolves tear hunks of meat from the yet-living body of the young elk. Overwhelmed and unable to resist, the elks final moments of life are grisly and bloody. Pausing in flight, the elk herd looks backward upon the carnage. One life, rapidly ripped to shreds, feeds the wolf pack for another day. Safe for a time, the elk herd moves on.

Night falls on a bloody patch of snow, bones, and fur.

On the clearest days of the winter solstice, fewer than nine hours of sunlight kiss the vast snowscape of this land of brutal survival juxtaposed with dazzling beauty and today known as Yellowstone National Park.

With the passing of the winter solstice, a brief period in which the Earths axis is tilted neither toward nor away from the sun, the planets tilt reverses, shifting back toward the sun. Measured in mere seconds the first day, more life-giving energy arrives upon Yellowstones remote wilderness.

Near the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone River a grizzly searches for a meal after a long winter season. COPYRIGHT BRUCE GOURLEY

Although six months of increasing daylight begins, bitter cold remains for about three more months, the suns rays too feeble to break winters spell. Some days snowstorms blanket the entirety of the Yellowstone plateau, obscuring sky and landscape alike. At other times flakes drift down leisurely from overcast skies. Howling windstorms often signal a transition in weather patterns. Suspended above the ground on some sub-zero, clear sunny days, tiny ice crystals shimmer and sparkle like playful diamonds in miniature. On the snow-covered ground, stationary ice crystals blink in flashes of silver as the blazing sun to the south slings low across the deep blue sky.

A primordial quietness bathes the winterscape of Yellowstones mountain-ringed valleys. Seemingly stretching forever, the silence from time to time is broken by the distant howl of wolves. Witnessed by few humans ancient or modern, the magnificence of the winter landscape in this remote corner of the world is unmatched. A cathedral of nature evoking reverence, winter in Yellowstone is also baptizedfrom predatory wolf kills to death by freezing on the part of weakened animals, fish, and birds alikewith bloody, life-giving sacrifices.

In a world of extreme cold, life, apart from the rush of the wolf hunt, moves in slow motion. While seeking scant food, ungulates instinctively conserve precious calories, each movement acting like a sacred act of sustenance.

A soft swishing sound is that of a shaggy beast buried chest deep in the snow and resolutely swinging its massive head from side to side like a pendulum. Left, right, left, right. With each arc a small indentation in the whiteness grows deeper. This is the lot of the American bisoncommonly known as buffaloin the winter Wonderland of Yellowstone. Its head crusted with ice but a thick protective winter coat keeping its body warm, the bison searches for dormant vegetation yielding scant but necessary sustenance. Each day of survival in the depths of winter is a quiet victory.

But listen closely, for the bison is not alone. Drifting across the quietness with astonishing clarity is a rhythmic grinding noise. It is a bighorn sheep, a connoisseur of different fare. Nimbly the bighorn stands upon a sun-exposed rocky promontory, the uneven terrain sparse with snow but off limits to the tank-like bison. Big glassy eyes fixated in the distance, the bighorn methodically chews on tough vegetation often avoided by other ungulates.