I n a later era, you would have called the relationship dysfunctional. In 1891, the Toronto Railway Company signed a thirty-year exclusive franchise to operate streetcars in Toronto. Things went well at first, but by the end of the decade, the honeymoon was over. A suit brought by the city in 1899 alleging that the TRC was overcrowding its streetcars ignited a decade of litigation, on that matter and others, at tribunals and courts in two countries.

Things reached a low point (or high point, depending on your view), when the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London weighed in, ruling that the TRC had no obligation to provide service beyond Torontos 1891 boundaries. It meant that the rapidly expanding city had to build and operate its own lines in areas annexed after that date, along routes such as St. Clair, Danforth, and Gerrard Street east of Greenwood.

Even as the city complained of the ludicrousness of having two streetcar systems in a single municipality, one private and one public, it forbade the privately run streetcar lines that connected Toronto to other towns known as radial railways from crossing the city limits. In Toronto, a northern radial line called the Metropolitan followed Yonge Street down from Lake Simcoe, but its passengers had to get off north of Summerhill. Similarly, cars on the eastern Scarborough line, the western Port Credit line, and northwestern lines along Dundas and Keele were forbidden to actually enter the city. The problem was, the radials were run by TRC affiliates, and the city refused to do anything that might give the hated company a further toehold in Toronto, even if it meant another point of transfer for travellers.

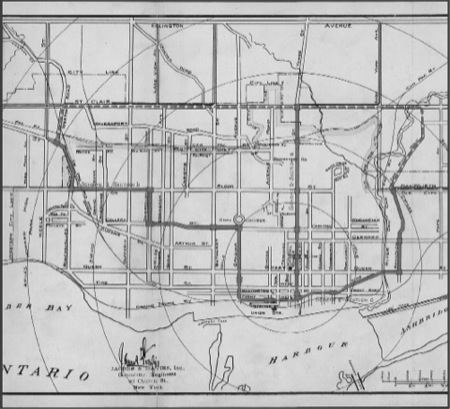

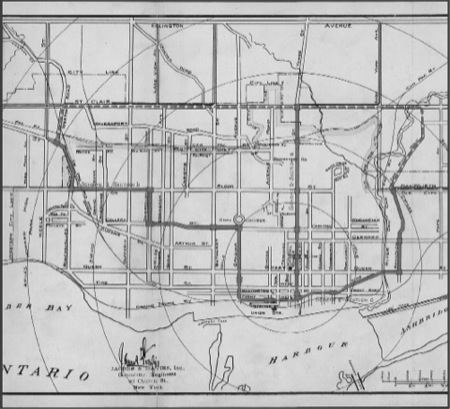

Fig. 3-1. The preferred route of the subway plan proposed in 1910 by the New York engineering firm Jacobs and Davies. [City of Toronto Archives, Series 60, Item 22.]

The TRC may have had the exclusive right to run transit on Torontos streets, but that didnt prevent the city from building it under those streets. In the run-up to the municipal election held on January 1, 1910, controller Horatio C. Hocken seized on this loophole, campaigning for mayor on a promise to bring tubes to Toronto. And in 1909, the future was underground. The year before, Boston had undertaken a third expansion of the streetcar subway system it had opened in 1898, New Yorks subway system had been up and running for five years, and across North America, cities large and small were considering subway proposals of their own. In Toronto, disenchantment with the TRC provided additional incentive.

Although the voters rejected Hocken, they didnt reject his vision, overwhelmingly approving a ballot question allowing the city to seek provincial approval for a subway system. The province responded swiftly, passing a bill in March 1910 that permitted Toronto to build and operate a system of underground railways for the carriage and transportation of passengers and freight.

The next step was figuring out what it should look like. In May council commissioned the New York engineering firm Jacobs and Davies to prepare a report on the matter. Written by engineer James Forgie, it was released three months later. Despite the widespread dislike of the TRC locally, he concluded that streetcar service in Toronto was actually pretty good, and would adequately serve the city for several years to come. This didnt mean that Toronto shouldnt be thinking to the years beyond that, however. Or, in the reports words, grasping time by the forelock.

Forgie proposed a subway scheme consisting of three parts: a line on Yonge Street from St. Clair to Wellington; a line from Broadview and Danforth to Front and Yonge; and a line from Front and Yonge to Dundas and Keele. Ultimately, these lines could form part of a circle route connected by a St. Clair line in the north. The system would be fed by an expanded streetcar and radial system. The entire tube portion could be built for just under $24 million (Fig. 3-1).

If economy dictated that the city build in stages, the report recommended starting on Yonge. As a cheaper overall alternative, the report suggested that the city could build the Yonge line, augmented with a line running east along Bloor Street and the Danforth. The report pointed out that this alternative would require the construction of a double-decker viaduct across the Don Valley a suggestion that was realized eight years later with the completion of the Prince Edward Viaduct.

Tubes may have made a lot of sense, but in Jacobs and Daviess view, not if they were going to be operated in competition with the TRCs existing streetcar system as the city proposed. On that point, if council needed experts to tell it the obvious, it got its moneys worth.

Undaunted, in 1911 the city actually sought bids for the construction of cement tubes for a northsouth subway between Front Street and St. Clair Avenue. It followed the alignment of modern-day Bay Street, switching to a Yonge-Street alignment north of Davenport. E.L. Cousins, the assistant city engineer, planned it as part of a broader scheme that included a Bloor-Danforth line and a Queen line. In the municipal elections of 1912, however, voters rejected the $5.4-million expenditure needed to build the northsouth line that was supposed to be the start of it all.

Fig. 3-2. Mayor Tommy Church (left) with Sir Adam Beck (centre). This picture was taken around 1916, a time when both men were deeply involved in proposals that would have seen Toronto as a hub for a system of intercity electrical railways. [City of Toronto Archives, Fonds 1244, Item 2465.]

With no realistic prospect of subways any time soon, the city turned its attention to fixing its relationship with the TRC by trying to get the company out of the picture altogether. In order to bolster its case that the TRC was in breach of its contract, the city hired Chicago-based transit consultant Bion J. Arnold to study the TRCs streetcar operations. Unlike Jacobs and Davies, he found them lacking. Subsequent meetings between the city and the TRC led to a tentative deal the next year, under which the city would pay the streetcar company $22 million to take over the system eight years early, and another $8 million to buy a hydroelectric company owned by the TRC.

Not everyone was happy. Tommy Church, a member of the citys board of control, considered it a boondoggle that gave the TRC a windfall. Even though the First World War had made financing the purchase impossible in the short term, Church made it a major issue in the 1915 mayoral race, taking his victory as an anti-TRC mandate. In his inaugural speech, Church called for the immediate creation of a special committee to consider the issue of radial railway access to the city and rapid transit generally (Fig. 3-2).

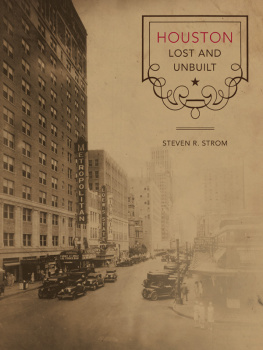

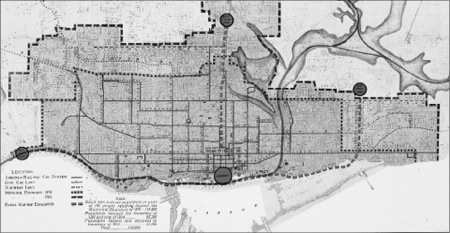

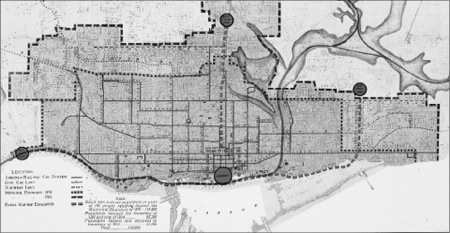

Fig. 3-3. In 1915, representatives of the city, the Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario and the Toronto Harbour Commission prepared a report on radial railway entrances and rapid transit for Toronto. It recommended three focal points through which radial railways would enter the city, travelling in open cuts, on elevated tracks and in tunnels. [Toronto Public Library.]