Acknowledgments

This book developed from many discussions with students and colleagues on why and how to analyse case studies and why this is relevant to design methods and design research. Many of the included projects continuously re-emerged in conversations on design.

I am grateful to all those who have contributed to the book, often in more than one way. Without them, it would not have been possible. The direct and indirect contributions included reviews of the book proposal, debates of case studies, helping with the production of drawings, provision of essential drawing material, analysis and sources, and permission to use drawings and images for reproduction. I thank: Adrian Lahoud, Alvaro Arancibia Tagle, Aristide Antonas, Charles Rice, Chen Shao, Christopher Lee, Cyan Jingru Cheng, Freda Yuen, Gabriella Nunes Pinta Gama, Guillem Pons, Hillia Lee, Jie Zhu, Ji Yoon Gu, Leonhard Clemens, Longning Qi, Marcin Ganczarski, Miao Yu, Monia De Marchi, Naina Gupta, Qinhe Yi, Runze Zhang, Seokjae Song, Simon Goddard, Shazia Ahmed, Tarsha Finney, Tianyi Shu, Ungers Archive for Architectural Research (UAA), Valerio Massaro, Yana Petrova, Yang Sun, Yating Song, Yu-Hsiang Hung and Yuwei Wang. The book would, of course, also not exist without the unwitting contribution by the authors of the analysed projects and, as I believe, their critical knowledge of precedents.

I am especially indebted to Sakiko Goto and her tremendous assistance in researching the case studies and producing the drawings. Without her tireless efforts, this book would not exist.

Thank you also to the editorial team Calver Lezama, Miriam Murphy and David Sassian, but especially to Helen Castle at Wiley for supporting the book and their patience.

The research was financially supported by the Architectural Research Fund from the Bartlett School of Architecture, University College London.

This edition first published 2016

2016 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Registered office

John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate,

Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, United Kingdom

For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Wiley publishes in a variety of print and electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some material included with standard print versions of this book may not be included in e-books or in print-ondemand. If this book refers to media such as a CD or DVD that is not included in the version you purchased, you may download this material at http://booksupport.wiley.com. For more information about Wiley products, visit www.wiley.com.

Designations used by companies to distinguish their products are often claimed as trademarks. All brand names and product names used in this book are trade names, service marks, trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. The publisher is not associated with any product or vendor mentioned in this book.

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: while the publisher and author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. It is sold on the understanding that the publisher is not engaged in rendering professional services and neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for damages arising herefrom. If professional advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional should be sought.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-118-87940-5 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-118-87947-4 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-87949-8 (ebk)

ISBN 978-1-118-87950-4 (ebk)

Executive Commissioning Editor: Helen Castle

Project Editor: Miriam Murphy

Assistant Editor: Calver Lezama

Cover design, page design and layouts by Artmedia, London

Printed in Italy by Printer Trento Srl

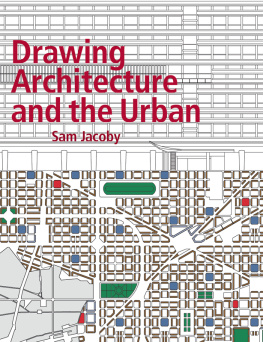

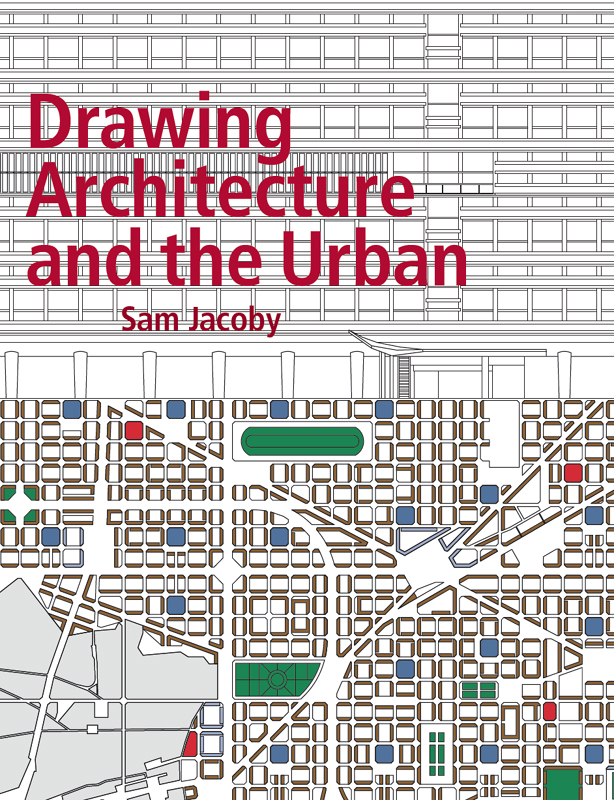

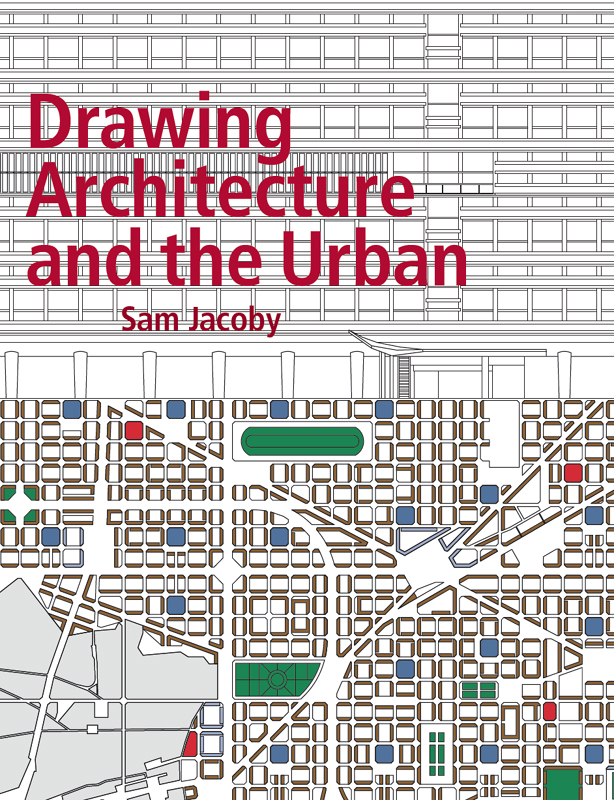

Cover images Sam Jacoby with Sakiko Goto

For further content go to: www.wiley.com/go/drawingarchitecture

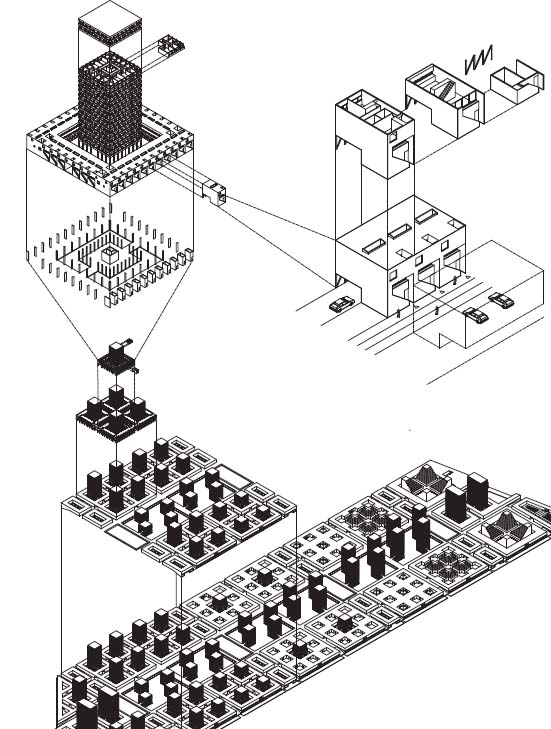

Alvaro Arancibia Tagle, Cit Housing in Santiago de Chile (AA Projective Cities, 2013)

Introduction

DESCRIPTION, ANALYSIS AND TRANSFORMATION

DRAWING AS DIAGRAM

Drawing is the basic means to communicate and reason an architectural or urban design. During the design process, drawings are produced that describe, analyse and generate ideas and structures. Yet in architectural drawings, these three modes overlap and are often difficult to distinguish. Description of architectural designs through graphic representation always requires some abstraction of reality and is therefore partially analytical. Analysis itself depends on conventions of description and often a comparison to established norms. And a generative drawing frequently is the conclusion of a comparative analysis, especially when deriving from a design method based on case studies. A sketch then can be descriptive, analytical and generative, depending on its context. In fact, context is critical to all drawings. We read a drawing differently when it is presented by students to explain a speculative project, is used by designers and clients to discuss how quantitative or aesthetic requirements are met, or is part of a tender package detailing building parts and elements for construction. Different drawing conventions have thus developed that are suitable to each context.

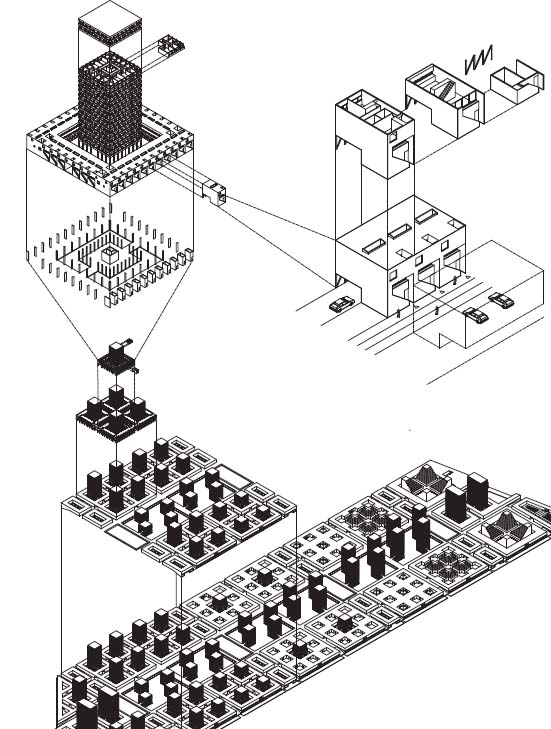

Defined by the interactions between description, analysis and generation, architectural and urban drawings are diagrammatic reductions that generally convey abstract spatial relationships and orders which can serve as blueprints for building. To materialise physically what are, despite representing a reality, essentially conceptual ideas, translation is required, as a diagram substantially differs from the reality it describes. But whether a project is meant for realisation or not, the principle of conceptual and material transformation is part of all design relying on representation and its translation. Any spatial concept is generative and can always be realised at different scales and in different materials, in each case demanding a new analysis and set of drawings, details, construction methods, etc. Therefore, the generative can be defined in these terms as a transformation that follows from analysis. It is not simply an artistic vision. Drawing Architecture and the Urban is structured around the three principal concepts of drawing as a means of description, analysis and transformation.

The need for abstraction in architectural drawings is intensified by computer-aided design (CAD), as the idea of a single drawing is obsolete, and potentially an infinite number of drawings are produced from the same file. What seems a simple observation of a mechanical process has a significant effect on the way we can instrumentalise drawing and conceive its role. A drawing produced by CAD requires continuous rethinking of scale, detail and graphic design. While hand drawing emerged within a tradition of imitative representation, computer drawing is associated with a generative process of abstraction, in which generalisation and its transformations have become operative for design and its description a fact that is recognised in the building industry through the increasing use of building information modelling (BIM). Thus with CAD, the conventions and problems of drawing have changed from the logic of hand drawing. The inherently generative nature of CAD requires a new judgement as to what and how we draw indeed, even as to how we conceive a project. The great potential of the computer drawing and model partially explains why, during its rise in the 1990s, an entirely three-dimensional and self-referential formal generation was pursued that deliberately avoided being analytical. Computer generation was turned into an end. Yet this book is a return to an analytical approach. It argues through the drawings themselves that graphical thinking is a central means of architectural reasoning, one which with the advent of the computer has established not only new forms of analysis and graphic knowledge but also a new aesthetic and style.

Next page