CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

The maxim of the twentieth-century Italian philosopher Benedetto Croce, expression is intuition, explores the view that in thinking something through we need to have expressed it. This expression may be given many intellectual forms but for a designer, drawing is the essential medium.

For a designer, drawing is not a creative process in the same way that it is for a fine artist. Drawing is thinking, and the constant construction and deconstruction of concepts and ideas happens with a pencil in the hand. Drawing is also communication; the drawings must talk to a viewer even when the designer is not present. This talking with your mouth shut continues through the various drawings the designer produces for him or herself to progress their ideas, and through those presentation drawings that they will eventually use to convey these ideas and chosen atmosphere to the client.

So the process of drawing has two distinct uses for those aspiring to a career in design. It is both a tool to aid the design process and a method of communication with an audience.

The Purposes of Interior Design

Drawing is clearly relevant to many design disciplines, but the specific applications in relation to interior design are best understood through an investigation of why interior space is so important and the nature of an interior designers agenda. First, interior design is not simply about things, it is not about filling spaces with aesthetically pleasing or culturally and historically relevant objects. It is certainly not about merely changing the colour of the walls, throwing a few cushions around and getting excited about tassels! It is first and foremost about space, refining or remodelling it to serve a new function, create a new atmosphere or correct perceived defects such as awkward proportions.

The task of an interior designer is to create habitable space. This applies whether considering residential or commercial spaces we spend so much time working that the office is often more occupied than the home. For habitable space to work it must perform well as regards function and it must have an aesthetic appeal to the people that are going to spend time there. Most importantly, it should elicit an emotional response; it should make you feel something. The latter is perhaps the most difficult to achieve but it is this aspect that turns good design into great design. Successful spaces make us feel differently. Spirit of Place is often most recognized when applied to exterior spaces, such as natural landscapes, but it is just as relevant to consider interior spaces in these terms.

Emotional responses to spaces are more easily identified when the space has a specific overriding function as with a place of worship, for example. Try to imagine a simple peasant farmer, in the year 1260, arriving in Paris from the countryside to be faced with the newly completed cathedral of Notre Dame. The sheer scale and impact of the building itself would be powerful beyond words. Larger than anything in the surrounding area, the cathedral would have been seen by our farmer from miles outside the city, adding to the anticipation.

Once through the main doors you must add spiritual awe to the response evoked by the power and scale of the place. As our farmer looks inside the House of God, what would he experience? First, he would see an extraordinary change in light quality, with shafts of sunlight filtering through stained glass, splintering light and vibrant colour across a space so vast as to be almost incomprehensible. He would see soaring arches, spanning so far and so high they cannot be properly discerned; the hushed, respectful behaviour of worshippers; the smell of incense; and the splendour of the gothic interior all on a scale to make any visitor feel small. He would sense religion and power emanating from every carved block.

This is a long way from a contemporary residential brief, but a request as simple as a comfortable home has its roots in more primal reactions to our surroundings. Just as a cathedral can tap into a whole raft of emotional history, so then can a home. An interior designer has to be aware of the key principles on which human beings base their need for interior space. Protection from the elements is of course primary, and this is wrapped up with security and feelings of comfort. This particular need was just as relevant, perhaps more so, when as prehistoric man we began to inhabit caves and chose to occupy particular defensible positions. The need to control a space, to be able to see but perhaps not be seen, stems from a prospect and refuge duality that we still seem to require. This is as relevant if you are protecting your family from sabre-toothed tigers or indeed exercising a preference for that corner table in your favourite restaurant. You choose a position where all routes are visible and no one can get behind you you can eat without being eaten! Your comfort zone is catered for. Scratch a business man travelling on the London underground system and this prehistoric caveman is not so far below the surface.

The complexities of why we use space the way we do makes for an interesting study, and those serious about interior design need to examine the thoughts of those designers and thinkers who have documented their ideas. Aside from the more populist writings of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, for example, students of design should look to Gottfried Semper, Gaston Bachelard and Juhani Pallasmaa for a more in-depth discussion of how mans development, biologically, sensually and aesthetically, affects his understanding and appreciation of the environment he occupies.

So habitable space is fairly complex, it involves general assumptions and conclusions combined with information specific to your client. Cultural background, experiences in childhood, things we have read and the visual ideas by which we have been influenced all contribute to the personal veneer that sits on the more common denominator, the base level that defines us and our shared human heritage. The articulation and communication of this complex atmosphere is the task of the interior designer.

Methods of Communication in Interior Design

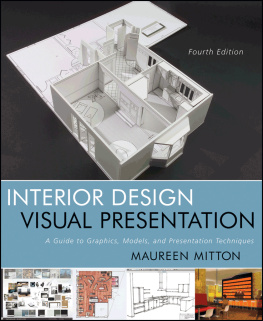

The designers drawings must show the factual aspect of the design. Plans indicate function, circulation and the routes and destinations of the occupier. Elevations show the balance of the more 2D aspects of the design. Sections explain levels and vertical progression through the space, and 3D drawing and sketching give the best indication of what the occupier will see, and hopefully feel, when in this newly designed space.

Interior designers must concern themselves with detail as well as overall concepts, and the drawing methods listed above will work across many scales and styles of visual explanation. Primarily an interior designer is concerned with space and understanding its use, and developing an understanding of how the proposed occupant of the space will use it is a crucial stage in the design process. Drawing informs this understanding in both cases. So how can this understanding in practical terms affect working method? There are three key stages to design method:

- Survey

- Design analysis

- Design

Within each of these more complex areas there is a key role for drawing and visual communication. It is the drawn elements of each of these stages that we will concern ourselves with within the covers of this book.

A designer needs to understand the space before there is any proposal to change it. This requires a survey of the existing space, namely the gathering of empirical information and the production of a measured drawing that details the dimensions and conditions of the existing building or room. To do this you need a method to measure the space (a survey), but in terms of drawing you need to be able to record quickly and efficiently those elements that would be laborious to explain in words or cannot be captured well in photographic terms. Often a drawing will communicate the designers reaction to the space in a clearer manner, above and beyond the mathematical aspect of the survey. Sketching to record what you see and understand is a large part of a survey, and developing an accurate method of visual shorthand is a great asset.