Foreword

Drawing is primal. It is instinctual. It is something all of us have done, whether we are making shapes or forming letters or simply moving a pencil across the page. At some point in our lives, we have all been compelled to use our hands to express an internal idea. We have all been compelled to draw.

For the last thirty years, hand drawing has been a constant part of how I solve design issues. In the beginning, I spent more time on the drawing board developing working drawings. As I have gained experience and tools have changed, I spend less time hand drawing, but in that time, I more quickly get to the root of the design issue.

We often talk about drawing through an architecture. Drawing is the most immediate way to bring architecture to lifewe cannot understand how a space will feel and function until we give it form. Drawing is the middle ground where we can let an idea live outside of ourselves and give it enough distance so that we might examine it and communicate with it. Sketching is an act of experimentationthe pencil is the tool and the drawing is the hypothesis.

More than that, when we draw by hand, we make an intimate link between our existential being and the outside world. The pencil becomes an extension of the hand, the body, the self. The sketch is a communication between inside and outside. Drawing is the imperfect but poetic process of attempting to make a connection between an external reality and our internal impulses.

Today, digital drawings are the standard in our field, and that is not going to change. We will never go back to hand drawing technical details. But we do often hand sketch on top of digitally generated drawings. I do this all the time, and I see younger architects doing the same. It is a practice that marks an evolution from both people who think with pencils and those who work more comfortably through a digital model, though in my experience, architects who hand draw a design always do a better job of executing proportion and design fit and finish than those who work exclusively with digital models.

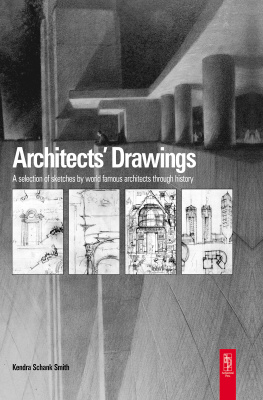

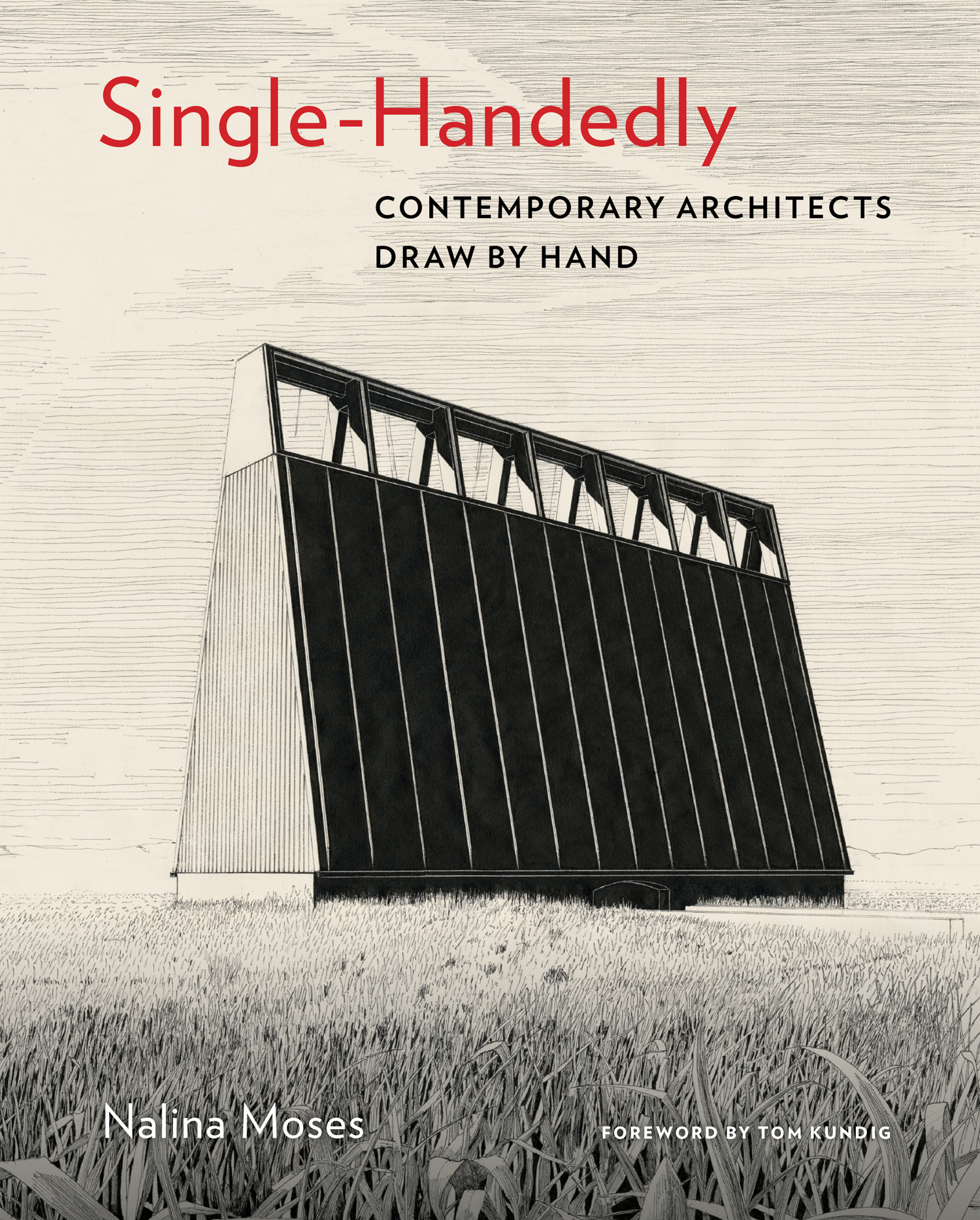

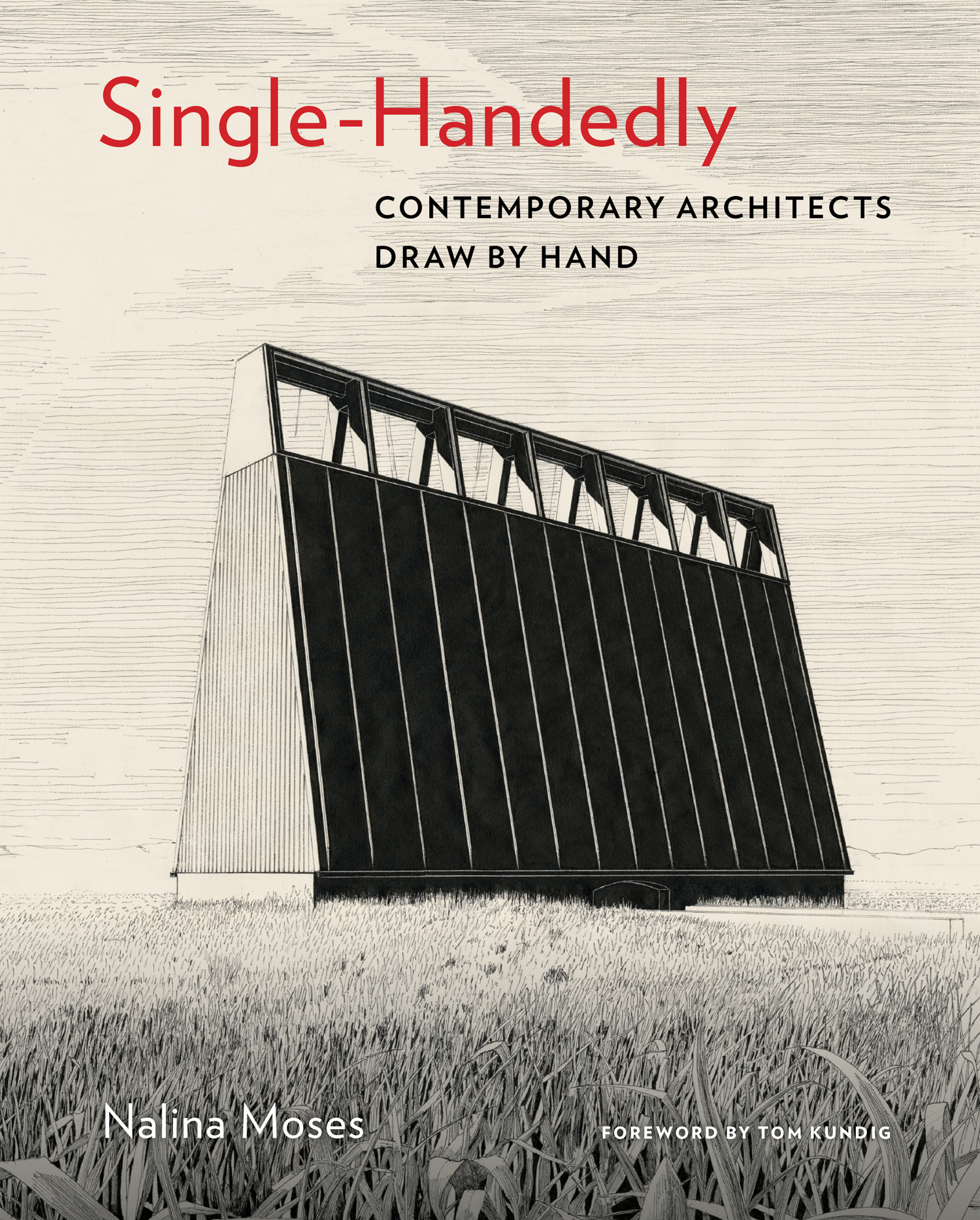

Architect and author Nalina Moses has gathered hundreds of sketches from architects around the world who, despite the increasingly digitized landscape of design, find value in drawing by hand. These sketches are alternately pragmatic, documentary, and imaginative. Seen together, they confirm that hand drawing remains fertile creative territory for architects around the world.

As this book demonstrates, drawing is where we explore an inner poetry. This process is not unlike that of composers who create music or mathematicians who formulate equations. There is beauty in this act of creation. One of my heroes, a Hungarian mathematician named Paul Erds, understood this well. When asked why numbers were beautiful, he replied, Its like asking why Ludwig van Beethovens Ninth Symphony is beautiful. If you dont see why, someone cant tell you. I know numbers are beautiful. If they arent beautiful, nothing is.

I know an idea is working on the page when I can feel the beauty of it. I cant explain how or why, but I sense it on a deeper level. I can hear it like music.

Tom Kundig, FAIA, RIBA

Preface

I started working as an architect in 1994, at that moment when production work was migrating from the drafting board to the computer screen. Renderings and drawings, which for centuries had been produced by hand, were now also being generated with computer-aided design (CAD) software. Even conceptual studies, which are often critical in establishing the character of a building, were being completed with the computer. Like most architects of my generation, I learned to draw both ways.

This movement from manual to electronic processes was part of a larger culture-wide shift. In architecture, a fundamentally physical art, it caused a deep, perhaps irreparable, fissure. The fallout is apparent in our cities today, a generation later. Major new buildings that have been executed with CAD often have a hollow, imagistic aspect. They feel less like structures than projections. In place of physical charisma, they offer a seamless, sophisticated sheen.

After decades of using CAD almost exclusively, Ive begun to draw by hand more and more for professional projects, particularly during early stages of design. Its faster, more direct, and more pleasurable than using a computer, and sometimes a preconscious intelligence intervenes, inspiring fresh solutions. As my own methods shifted, I started wondering if other architects were alsosometimes turning away from the computer, and if hand drawing might have the potential to revitalize the design process.

I began to work on this book by soliciting hand drawings from architects, posting an open call online and reaching out to dozens of practitioners directly. I received submissions from almost four hundred architects. They included architects from Thessaloniki, Moscow, Kuala Lumpur, and Brooklyn. They included prize-winning architects with thriving practices, emerging talents with only a few built projects, and young architects struggling to find work. Almost all of the drawings were completed between 1990 and the present, a time when computer drafting has dominated production.

As I reviewed the drawings, I was amazed by their variety and energy. They included drawings of classical monuments, apocalyptic cityscapes, and garbage-collecting blimps. They included drawings crafted with acrylic paint, coffee, and correction fluid; drawings rendered on Mylar, yellowed notebook pages, and USGS maps. A great number of them were beautiful. Of these, some also possessed an expressive urgency, as if they needed to be drawn. Its these that made their way into the book.

More than two decades after the shift to computer drafting, architects continue to draw by hand, both professionally and personally. For some its a private step in the design process, or an informal way to share ideas with team members. For others its a practice that supplements their professional work, exercising an untapped imagination. Even though these drawings usually arent released for presentation or construction, remaining largely hidden, the ideas they give expression to can leave traces in our buildings and our environment.

As is evident from the work here, hand drawing remains a fertile, potentially transformative, creative territory. While the computer will remain central to architectural production, I hope that the hand also remains present, and potent.

Many others made important contributions to this book. My editor, Abby Bussel, encouraged me to follow my ideas. My brother, Vijay Moses, and my friend Ajanta Mukherjee managed practical matters. My parents, John and Gracia Moses, offered endless support. And hundreds of talented architects shared their work.

Nalina Moses

New York, 2018

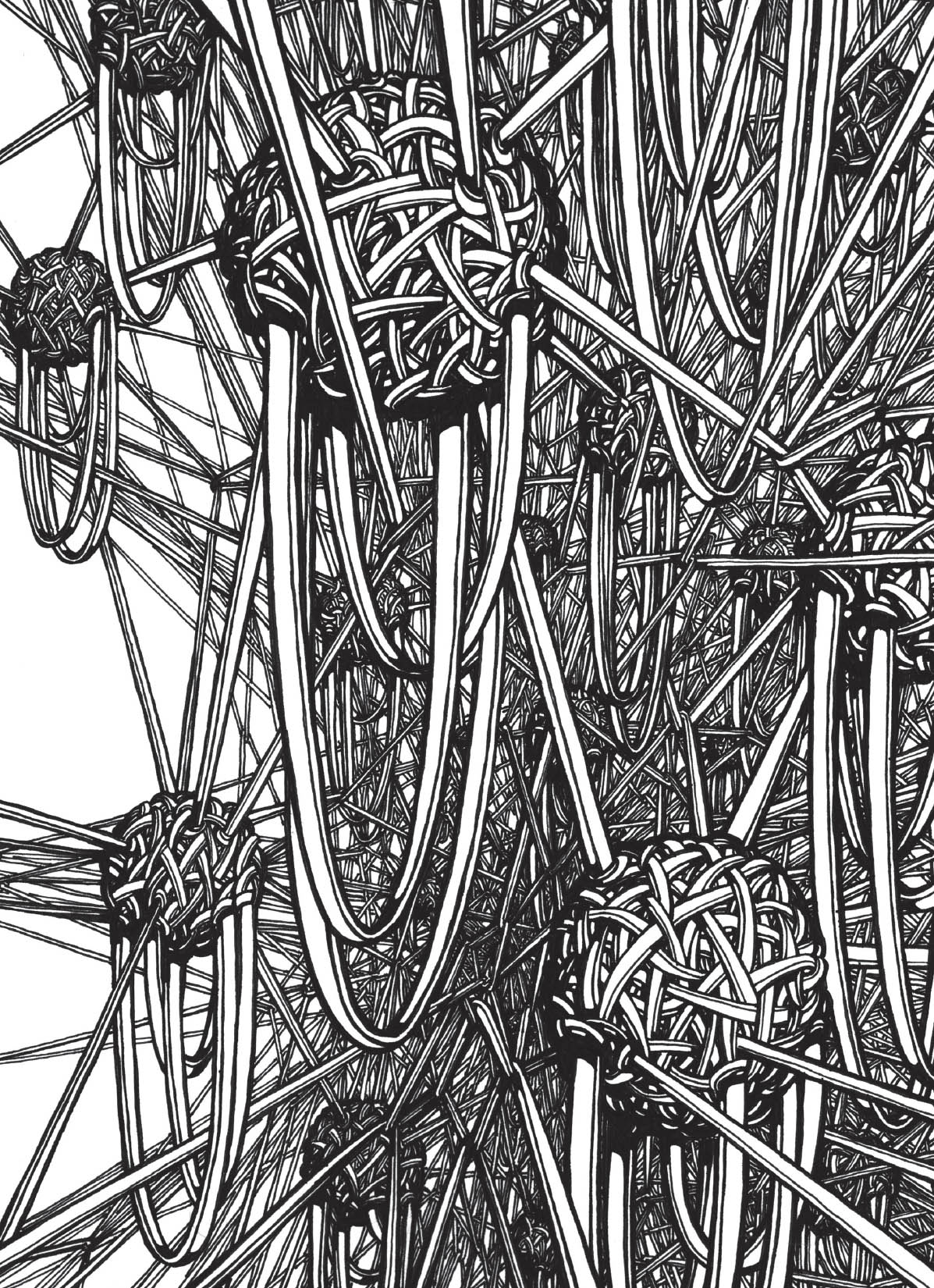

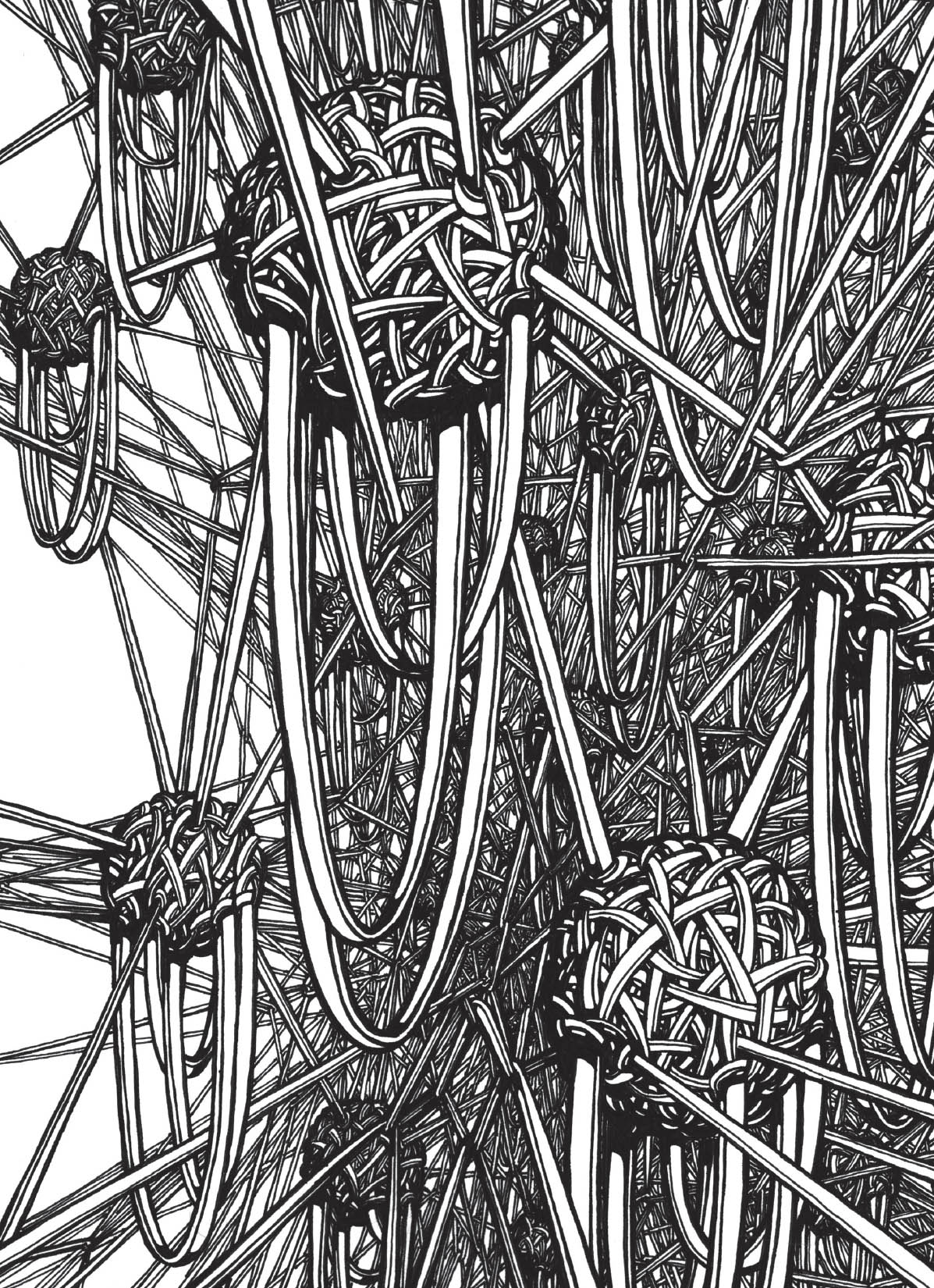

Detail from Lineworks 4.1, Dwayne Oyler, 2013.

Introduction

Handled with Care: Manual Drawing in a Digital Age

While architects today complete production work with state-of-the-art imaging technologies, many also continue to draw by hand. There is something in the act itselfa physical expressionthat remains essential to architectural design. At the same time, there is a persistent lack in computer drawingan intellectual and imaginative blind spotthat calls to be addressed.

Next page