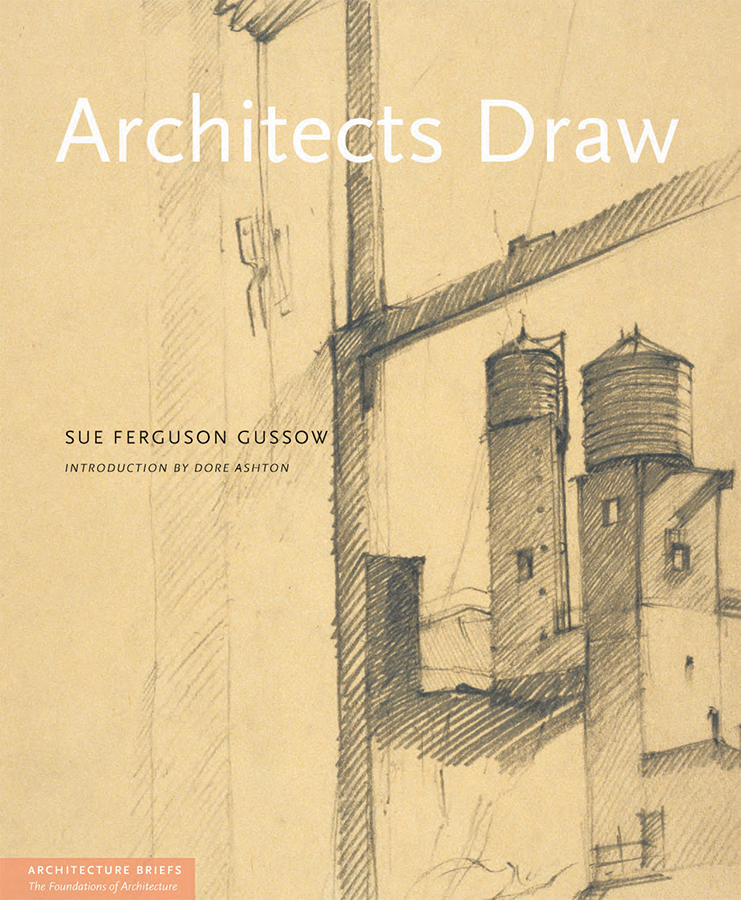

Architects Draw

SUE FERGUSON GUSSOW

Introduction by Dore Ashton

Princeton Architectural Press, New York

TO JOHN HEJDUK

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The realization of this book owes a debt to the many individuals who played a signal role in its development. From my initial notions of a book to the publication that has emerged, countless of my students drawings were culled through. The participation of many individuals and institutions was required.

The Graham Foundation and the Tides Foundation awarded generous grants. Anthony Vidler, dean of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture of The Cooper Union, allowed access to the photography collection of the schools Architecture Archive.

For their generosity and guidance, thanks are due to John de Cuevas and Sue Lonoff de Cuevas, Franois and Susan de Menil, and Toshiko Mori. My colleague Dore Ashton has been a mentor throughout. I wish particularly to thank my dear friend John Hejduk, the late dean emeritus of The Irwin S. Chanin School of Architecture, for the inception of this book. Over the years he would say, Sue, lets do a book, and to that end drawings would intermittently be saved. A quarter century has passed since he first made that statement, and some of the drawings now show the yellowing of years.

My thanks go especially to my colleague Steven Hillyer, director of The Cooper Union Architecture Archive and production editor of this book. His extensive talents, vision, clear-headedness, and devotion were a mainstay from start to finish. Gina Pollara, former associate director of the Archive, also provided significant support and expertise through a portion of the work.

Considerable skill and hours of devotion were given by the projects major assistants and former students, Yeon Wha Hong, Anne Romme, and Dan Webre. Also on board were Jesicka Alexander, Lis Cena, Deborah Ferrer, Kalle Lindgren, Alexander Wood, and Monica Shapiro, who holds the history of the School of Architecture in her mind.

It has been a great pleasure to work with Executive Editor Clare Jacobson and Editorial Director Jennifer Thompson of the Princeton Architectural Press in shaping the focus of this book. For her painstaking attention to detail and her thoughtful observations I especially thank editor Linda Lee.

I am grateful to my students themselvesmore than a thousand over nearly four decades of teachingfor their countless drawings and the passion they developed for the art of drawing. The rich diversity of their work and their words in response to projects set forth in these pages has further taught me how to teach.

Finally I thank my husband, Donald Gerard, for his patience in reading every single word, for the clarity (and necessity) of his critique, his editorial acuity, and most of all his enduring support and belief in the value of this book.

INTRODUCTION

THE FREE HAND

DORE ASHTON

The nature of the act of drawing has been discussed for centuriesan indication of how fundamental it is to human endeavor. During the Renaissance, a period of great architectural invention, it was often architects who fervently addressed the issue of drawing. And no wonder, since among the great architectsI think of Michelangelodrawing and painting were the natural accompaniments to the creation of articulated spaces. Speculative geniuses such as Leonardo never ceased pondering the nature of drawing, often making casual remarks in his journals of striking import, as when he characterized the contour line as possessing uno spessore invisible , an invisible thickness.

Old rumors have it that Nicolas Poussin said there were two ways of regarding: the first is merely to look and the second is to look with attention. Poussin was seconded by Goethe, whose remarks on drawing occur from his earliest success in the novels, The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774), to his enigmatic Elective Affinities (1809); in the latter he particularly reveals his proclivity for landscape architecture. That text is peppered with remarks about the importance of art and drawing in the architects life. Drawings give, in their purity, the mental attention of the artist, and they bring immediately before us the mood of his mind at the moment of creation. In speaking of the mood of the mind, Goethe reminds us of the mysterious fusion of eye, hand, and mind that we call drawing and assumes that drawing springs from the imagination, the only site for a mood of mind. It is a faculty indispensable for an architect.

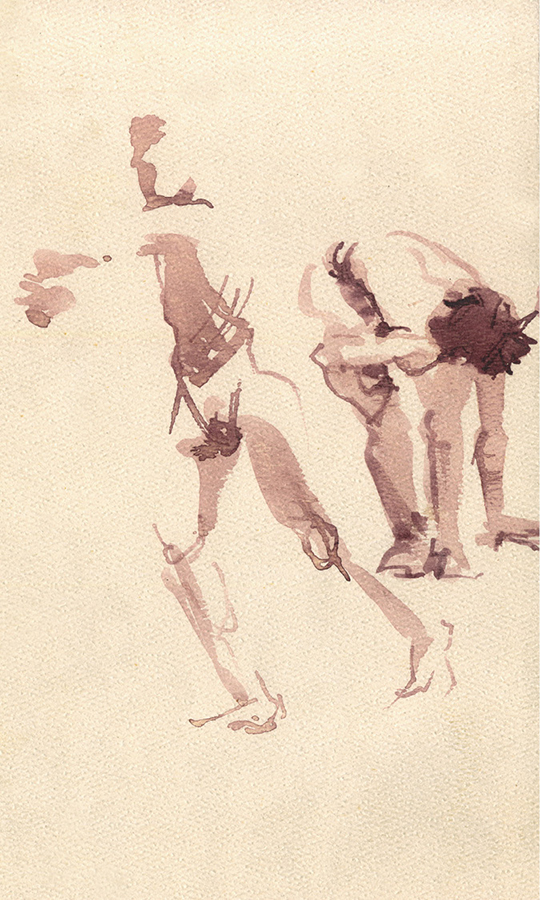

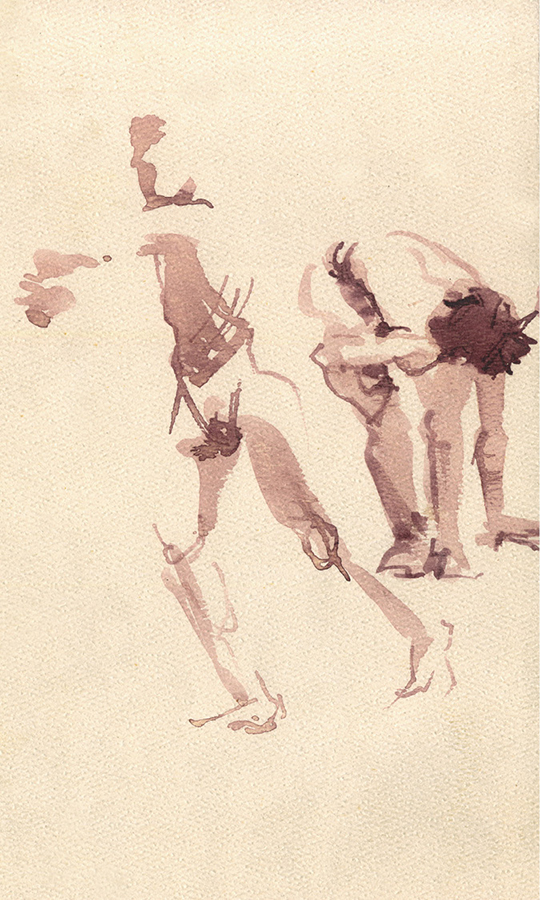

A draftsman is not a mere technician if he avails himself of what has long been called freehand drawing a term by which we condense ideas about the reciprocity of eye, hand, and mind. The very act of drawing, if freely engaged, is speculative to the highest degree. Just as there are no two hands alike, there are literally boundless possibilities in the hand of each when touching the vast blankness of a page. There are countless testimonies to the value of such explorations. I have always liked especially the words of the poet Paul Valry, who, while still a schoolboy, had the good fortune to watch Edgar Degas drawing, and was a decent draftsman himself. Valry observed:

There is an immense difference between seeing a thing without a pencil in the hand and seeing it while drawing it. Even the object most familiar to our eyes becomes totally different if one applies oneself to drawing it: one perceives that one didnt really know it, one had never really seen it.

Valry added a dictum from Ingres that he had heard from Degas: The pencil must have on the page the same delicacy as the fly who wanders on a pane of glass.

Above all other artists, architects require a firm sense of where. They must first locate themselves and then their composed objects in an ideal space before they can even begin the sequence of acts that constitute a construction.

Poets, artists, and architects inevitably seek the metaphorical dimension of space. It was one of the primary means of instruction in the years that John Hejduk developed the curriculum at The Cooper Union. Metaphor, as Aristotle thought, is a kind of enigma and, for a verbal artist, the greatest thing by far is to have a command of metaphor because this alone cannot be imparted by another; it is the mark of genius, for to make a good metaphor implies an eye for resemblances. The eye, Hejduk thought, must be cultivated for myriad resemblances in the Aristotelian sensethat is, through a poetic exploration of both inner and outer spaces. Probably The Cooper Union was the only school in the world that had thesis projects with such titles as A Blue House for Mallarm or The City of Fools.

Hejduk was not alone among modern architects honoring the imaginative extensions of metaphor. One has only to read Louis Kahns paeans to drawing scattered poetically throughout his writings to know how important his metaphorical sketches were to his architectural practice. There is a great difference, he knew, between drawing and rendering, and that difference made all the difference.

If we look at the sketchbooks of the renowned architects of the twentieth centuryLe Corbusier, Frank Lloyd Wright, Kahn, and a host of otherswe see immediately why the eighteenth-century French critics called the sketch a premiere pense , the initial thought. It would be the indispensable germ of the product we call architecture.

Hejduks ideas about the training of the architect found a perfect executrix in Sue Gussow. Her knowledge as a practicing artist extended far back in history. She taught her students the freedom to range everywhere in time and spacethat is, in the history of artists from cavemen onin order to understand the vast range of modes of expression. Architects were trained to attend to the myriad methods artists have found to express what Goethe called the mood of their minds, without inhibitions. She accustomed these future professionals to the quest for the unaccountable, the mystery in establishing a metaphor for lived experience. She gave them, in short, a free hand.

Next page