THE TAO OF ARCHITECTURE

THE TAO OF ARCHITECTURE

Amos Ih Tiao Chang

With a new foreword by David Wang

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 1956 Princeton University Press

Foreword to first Princeton Classics Edition

copyright 2017 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey

In the United Kingdom: Princeton Univeristy Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

All Rights Reserved

Formerly titled The Existence of Intangible Content in Architectonic Form Based upon the Practicality of Laotzus Philosophy

Printed in the United States of America

FIRST PRINCETON PAPERBACK printing, 1981

First Princeton Classics Edition, with a foreword by David Wang, 2017

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016960851

Princeton Classic Edition paperback ISBN: 978-0-691-17571-3

Printed on acid-free paper.

press.princeton.edu

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

FOREWORD TO THE PRINCETON CLASSICS EDITION

The Taoof Architecture was one of the first books that stirred a nascent question in me: How does philosophy relate to architecture? How indeed! That was well over thirty years ago. It is a pleasure now to write this foreword to Amos Changs book upon its re-release, and to revisit that question I asked long ago.

The formative years of Amos Ih Tiao Changs life (19161998) were tumultuous ones for China. Chang was born just five years after the fall of the last imperial dynasty, the Qing, in 1911. By the time he graduated from high school in 1935, the new Chinese nation had already gone through several attempts at national governance. During his college years at Chongqing University, the Japanese bombed the city repeatedly, as it was the seat of the Nationalist government during the second Sino-Japanese War.

This was clearly an educated man. What pertains for us is this: in what way was Chang an educated man? Prior to the twentieth century, neither engineering nor architecture were lines of professional pursuit in traditional Chinese culture. Up to 1905, and for centuries prior, young men (and it was always men) vied for good jobs and social standing by scoring well in civil service examinations based on the Confucian classics. The sea change in learning, from competence in Confucian metaphysics to mastery of the nuts and bolts of technologizing nature, is central to the question of how to define, for lack of a better term, Chinese modernity. Technologizing nature describes the harnessing of nature mechanically not only to increase human comfort, but also as the only way to define what is true. As we read The Tao of Architecture, it is helpful to keep this term in mind. What we have here is a work written by a thinker trained in disciplines of praxis originating in Europe-engineering and architecture-but processed through principles from ancient Chinese philosophy, specifically, the Daodejing. This blending of two ways-of-being permeates the pages of Changs book.

We can take this blending of Daoism with European characteristics as a negative, on the grounds that Chang does not stay true to a literal (whatever that means) application of Daoist principles. Or we can take this blending as a positive thing, for the following reason. At a time when critical theory consumes much of the oxygen of architectural theorizing, looking to Chinese sources to comprehend architectural concerns can be a fresh way to enrich design thinking and process. In this sense, Changs work sets an example. Permit me to add a personal note. Those of us design theorists who have roots in China but were trained in the West are largely a respectfulwhich is to say, a quietbunch. Maybe this is the result of a cultural disposition. But I believe that drawing on Chinese ideological sources more vocally to bring new perspectives on current architectural issues would be a significant contribution to the fieldand, of course, I dont limit this invitation to those of us who are ethnically Chinese.

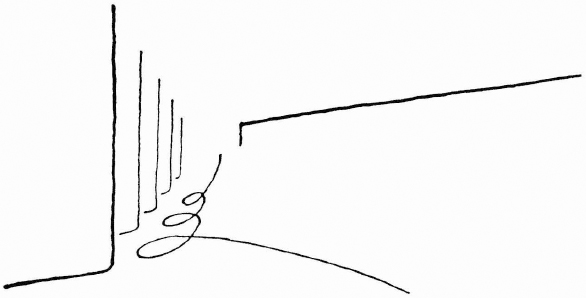

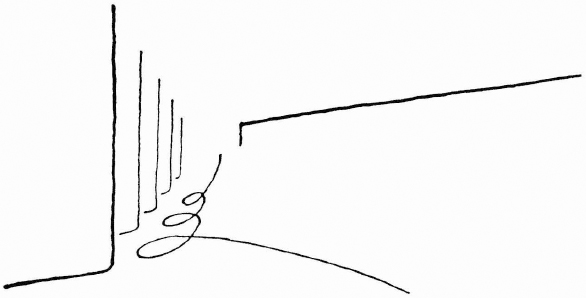

To introduce Changs work, I first provide a brief overview of Daoism to help readers see where Chang gains entre into the Daoist worldview. Second, I briefly review Changs chapters, which he does not number; nor does he provide any captions for his enigmatic line sketches that abound in the book. These ambiguities themselves in no small measure give Changs work a Daoist texture. But the reader would benefit from a general assessment of the major divisions. In the conclusion, following my own exhortation above, I offer brief thoughts about how Daoist ideas can inform architectural discourse moving forward at this, the beginning of a cyber revolution that may well change how we live in more fundamental ways than did the Industrial Revolution.

DAOISM

With one exception, There are more today.

The provenance of the Daodejing is an enduring topic of scholarship.

While the Daoism of the Daodejing does not teach total withdrawal from government, it does promote letting things be, as hermits would. You might live in one village and hear about the activities of a neighboring village, but not establish relations with it (Daodejing 80). And even though Daoism does recognize a ruler, this ruler is to do nothing, so that everything is done (Daodejing 37, 48, 57, 63). Who or what is the Daoist ruler? The ideal Daoist ruler is characterized by actionless action (wu2 wei2). For my students, rather than translate wu wei as actionless action, I render it letting nature flow through you. The Daoist ruler who does nothing is one through whom nature effortlessly flows, so that government, like everything else about him, is a spontaneous natural production. Hence the ruler himself is one who has no deliberative intentionality; in this (For his part, Chang refers to deor teon page 5, but does not define it).

But what is the first term of the Daodejing? What is Dao? Well, I cant say: The Dao that can be named is not the eternal Dao. This is the famous opening line of the Daodejing. In this mystical sense, the dao of Daoism is different from dao as used by the other schools. It is not a way or path in the sense of a prescriptive methodology. It is something like the fundamental essence of all being. It has resonance with Parmenides One, but Dao is more vital, more organic; Dao is more informative of ethical conduct than the abstract-propositional nature of Parmenides One. On the other hand, Dao is not the Christian God, because Dao itself is not a persona. (Chang himself makes a similar point on page II). For our purposes, Dao is the seat of all de; it is the fundamental of all things; it is an organic holism constantly, albeit namelessly, active, far beyond the capacity of any empirically confined or temporally visible being or construct to encompass or comprehend.

This mystical aspect of Dao would go on to have an enormous impact on Chinese ideas. Chang frequently invokes non-being, for example. In Daoism, non-being is a technical term that grew in significance from the Daodejing to the Zhuangzi, attributed to the important second generation Daoist philosopher of that name (370287 BCE); to commentaries on the Daodejing written during the Neo-Daoist period of the third the Zhuangzi invokes non-being to emphasize the absolute relativism of things:

Next page