A PHILOSOPHY OF CHINESE

ARCHITECTURE

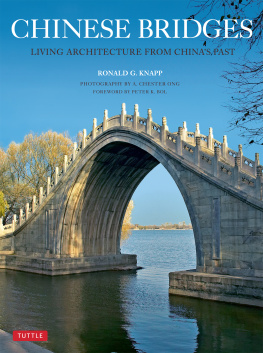

A Philosophy of Chinese Architecture: Past, Present, Future examines the impact of Chinese philosophy on Chinas historic structures, as well as on modern Chinese urban aesthetics and architectural forms. For architecture in China moving forward, author David Wang posits a theory, the New Virtualism, which links current trends in computational design with long-standing Chinese philosophical themes. The book also assesses twentieth-century Chinese architecture through the lenses of positivism, consciousness (phenomenology), and linguistics (structuralism and poststructuralism). Illustrated with over 70 black-and-white images, this book establishes philosophical baselines for assessing architectural developments in China, past, present, and future.

David Wang is Professor of Architecture in the School of Design and Construction, Washington State University. He holds BA and MArch degrees from the University of Pennsylvania, and the MS Arch and PhD from the University of Michigan. Dr. Wang has lectured widely on design research methods in China and the Scandinavian countries. This current book comes out of many years of teaching a comparative course in European and Chinese philosophies and their impact on architecture and material culture.

A PHILOSOPHY

OF CHINESE

ARCHITECTURE

Past, Present, Future

David Wang

First published 2017

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

and by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

2017 Taylor & Francis

The right of David Wang to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Wang, David, 1954- author.

Title: A philosophy of Chinese architecture : past, present, future / David Wang.

Description: New York, NY : Routledge, 2017. | Includes bibliographical

references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016020485| ISBN 9781138884601 (hardback : alk. paper) |

ISBN 9781138884618 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781315715995 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Architecture--Philosophy. | Architecture, Chinese. |

Architecture--China.

Classification: LCC NA2500 .W36 2017 | DDC 720.1--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016020485

ISBN: 978-1-138-88460-1 (hbk)

ISBN: 978-1-138-88461-8 (pbk)

ISBN: 978-1-315-71599-5 (ebk)

Acquisition Editor: Wendy Fuller

Editorial Assistant: Grace Harrison

Production Editor: Lisa Sharp

Typeset in Bembo and Stone Sans

by Florence Production Ltd, Stoodleigh, Devon, UK

To my father, and the memory of my mother

CONTENTS

PART I

Past

PART II

Present

PART III

Future

I am grateful to Washington State University for granting me the professional leave and financial resources to write this book. Thanks also to all my colleagues at the School of Design and Construction for making our academic home in the Palouse such a great place to teach, learn, write, and build together. Special thanks to Phil Gruen, Greg Kessler, Taiji Miyasaka, Carrie Vielle, and Saleh Kalantari. I am also grateful to these staff who facilitated this project: Jaime Rice, Cheryl Scott, Kimberly Clanton, and Darcie Young.

Academic colleagues in China helped in various ways, from hosting me, to arranging invited lectures, to taking me to all sorts of sites, to sharing examples of their work, to granting me hours of interviews: Liu Jiaping, Yang Liu, Wang Shusheng, Zhang Qun, Lei Zheng Dong, Cheng Hui, Li En, Li Baofeng, Lu Xiaohu (and his assistants Shyeah and Aris), Tan Gangyi, Mengyuan Xu, and Mary Polites. Also thanks to these practitioners and their associates: Sun Zhuo, Yung Ho Chang, Dang Qun, Bao Pao, Tammy Xie, Dong Gong, Chen Liu, Zhu Pei, Fiona Hua, Silas Chow, Li Hu, Cheng Chen, Hui Wang, Yan Meng, Jing Li, Yun and Sophie (Urbanus), Tao Huang, and Elaine Tsui.

Students at WSU also helped: Shannon Coughlin on market research for the book proposal; XiXi He on translation input; Qiongyan Gao on ordering books from China, and also contributing an image in ; Richard Tung on graphics; Ivan Schulz by asking me to be his advisor on his Honors research paper on Ma Yansong; and Holly Sowles by being my Teaching Assistant through much of the period this book was written.

Thanks to the doctoral students at the Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan. Many of their research topics gave me insight into current issues for architecture and urban design in China. Special thanks to: Ghassan Hassan, Gelareh Sadeghi, Zeyang Yu, Qian Ji, Lu Yang, Hu Ci, and Gan Wei.

I also want to thank Professors Xiao Hu, Delin Lai, Tom Verebes, and Andres Sevtsuk for sharing their research, images, and correspondence in this project.

My editors at Routledge were excellent: Wendy Fuller and Grace Harrison. I look forward to working with them again.

Finally, thanks to my wife and best friend, Valerie. I couldnt do any of this without you.

The sheer volume and speed of building construction in China today is unprecedented in human history. That old clich truly applies: one has to see it to believe it. So it is not surprising that the number of publications on Chinese architecture has increased in recent years, and the following pages will interact with this material. But this book approaches architecture in China in a way that, as far as I know, has not yet been taken in this literature, at least not to the length attempted here. I aim to ask: What is Chinese architecture? through the lens of Chinese philosophy. Readers may balk at even asking this question, because globalization and information technology have rendered national distinctiveness something of a dated concern. But let me explain why this is necessary.

Prior to 1840, there was no Chinese architecture. By this I mean architecture did not exist in China as a self-contained, philosophically focused object of contemplation. This is in contrast to the Greco-European West, at least since Vitruviuss Ten Books on Architecture dating from the first century BCE. A building must be firmitas, utilitas, venustas, wrote Vitruvius. answer this question. It is pertinent to the present situation because as architects in China grapple with what contemporary Chinese architecture ought to be, they are confronted with generating architectural theory in a philosophical tradition that does not offer a lineage of such ideas to draw from. All of it is de novo; and this novelty shows up in different ways in architecture in China today. This leads to the second reason why our question is needed.

Since 1840, What is Chinese architecture? remains contested ground. The year 1840 marks the First Opium War (it actually began in 1839), which is widely regarded as the starting point for Chinas entrance into the way of being called