Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt - Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200-600

Here you can read online Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt - Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200-600 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Honolulu, year: 2014, publisher: University of Hawaii Press, genre: Art / Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

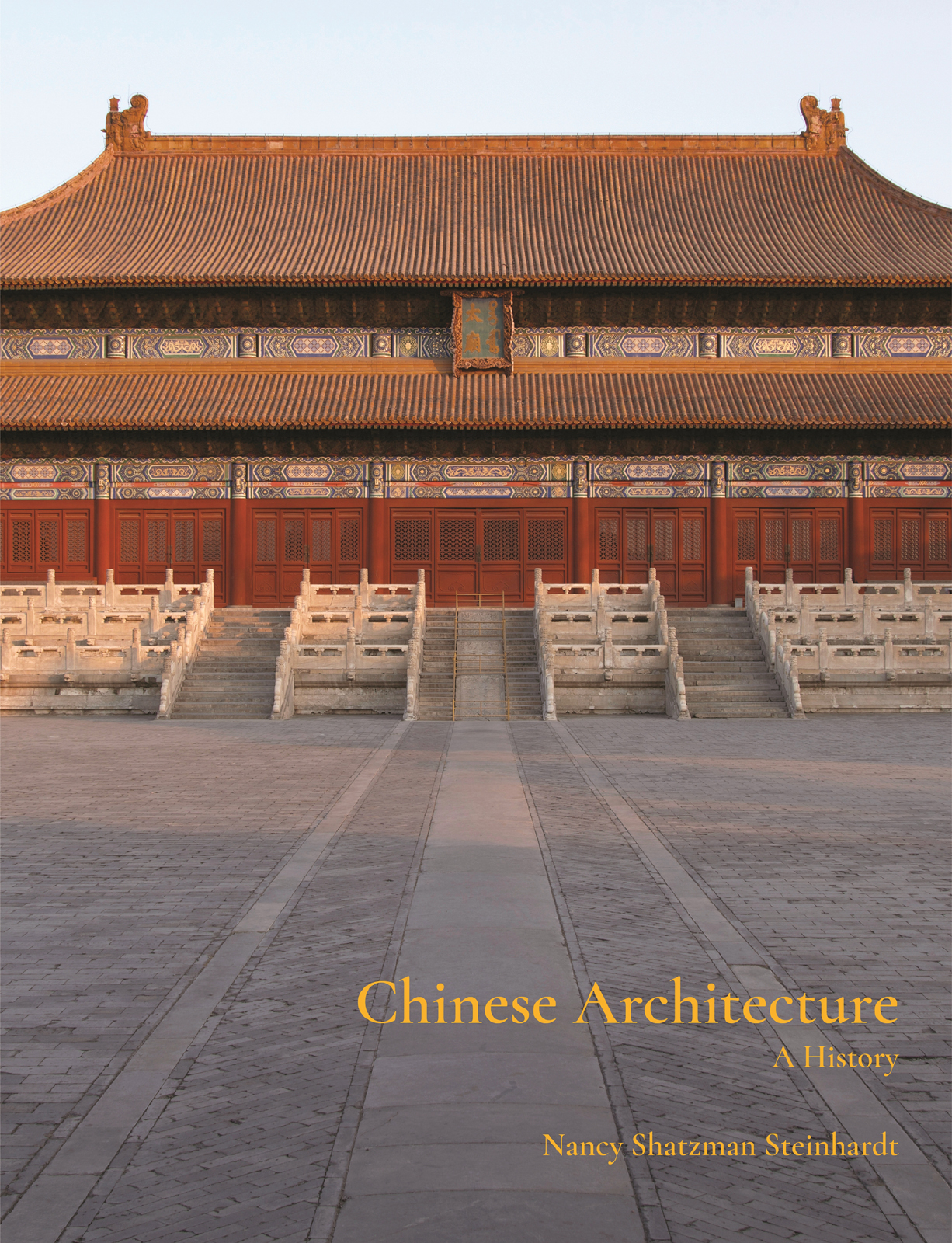

- Book:Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200-600

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Hawaii Press

- Genre:

- Year:2014

- City:Honolulu

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200-600: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200-600" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Between the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 CE and the year 600, more than thirty dynasties, kingdoms, and states rose and fell on the eastern side of the Asian continent. The founders and rulers of those polities represented the spectrum of peoples in North, East, and Central Asia. Nearly all of them built palaces, altars, temples, tombs, and cities, and almost without exception, the architecture was grounded in the building tradition of China. Illustrated with more than 475 color and black-and-white photographs, maps, and drawings, Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil uses all available evidenceChinese texts, secondary literature in six languages, excavation reports, and most important, physical remainsto present the architectural history of this tumultuous period in Chinas history. Its author, Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt, arguably North Americas leading scholar of premodern Chinese architecture, has done field research at nearly every site mentioned, many of which were unknown twenty years ago and have never been described in a Western language.

The physical remains are a handful of pagodas, dozens of cave-temples, thousands of tombs, small-scale evidence of architecture such as sarcophaguses, and countless representations of buildings in paint and relief sculpture. Together they narrate an expansive architectural history that offers the first in-depth study of the development, century-by-century, of Chinese architecture of third through the sixth centuries, plus a view of important buildings from the two hundred years before the third century and the resolution of architecture of this period in later construction. The subtext of this history is an examination of Chinese architecture that answers fundamental questions such as: What was achieved by a building system of standardized components? Why has this building tradition of perishable materials endured so long in China? Why did it have so much appeal to non-Chinese empire builders? Does contemporary architecture of Korea and Japan enhance our understanding of Chinese construction? How much of a role did Buddhism play in construction during the period under study? In answering these questions, the book focuses on the relation between cities and monuments and their heroic or powerful patrons, among them Cao Cao, Shi Hu, Empress Dowager Hu, Gao Huan, and lesser-known individuals. Specific and uniquely Chinese aspects of architecture are explained. The relevance of sweepingand sometimes uncomfortableconcepts relevant to the Chinese architectural tradition such as colonialism, diffusionism, and the role of historical memory also resonate though the book.

Nancy Shatzman Steinhardt: author's other books

Who wrote Chinese Architecture in an Age of Turmoil, 200-600? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.