FORTRESS 84

CHINESE WALLED CITIES 221 BCAD 1644

| STEPHEN TURNBULL | ILLUSTRATED BY STEVE NOON |

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

CONTENTS

CHINESE FORTIFIED CITIES 1500 BC AD 1644

INTRODUCTION

China possesses the worlds longest tradition of fortified buildings and settlements, yet the study of this has always been hampered by an understandable tendency for any researchers eyes to be irresistibly drawn towards the magnificent and romantic structure that is the Great Wall of China. This can unfortunately take ones attention away from the fine city walls that have protected not only Chinas capitals, but almost every urban community, for many centuries. Although nowadays they are often pierced by modern roads and railways, and sometimes have even been demolished to make room for them (Beijing being a notorious example), extensive sections of the walls of several of Chinas fortified cities still stand as splendid memorials of ancient defensive systems. There has, however, been a welcome trend within recent years for wholesale and usually sensitive restoration, so that many now look as formidable as they ever did and are often more rewarding to study than the famous Great Wall, because even though the defences of the finest fortified cities may appear to the casual eye as no more than the Great Wall in miniature, this is usually only in terms of the walls overall length. Other details are sometimes finer, because in contrast to the sometimes monotonous repetition of defensive features on the Great Wall, the city walls have a variety and an intricacy about them that their big brother lacks. Nowhere do they defer to it in width or height, nor in the splendour of their gateways and their towers. Also, unlike much of the Great Wall, Chinese city walls saw a lively operational history, an uncomfortable fact of life for the inhabitants who depended upon them so often in the nations violent history.

The Shang dynasty wall made from rammed earth at Zhengzhou. These are probably the most ancient surviving walls in China, and are used today almost as a public park.

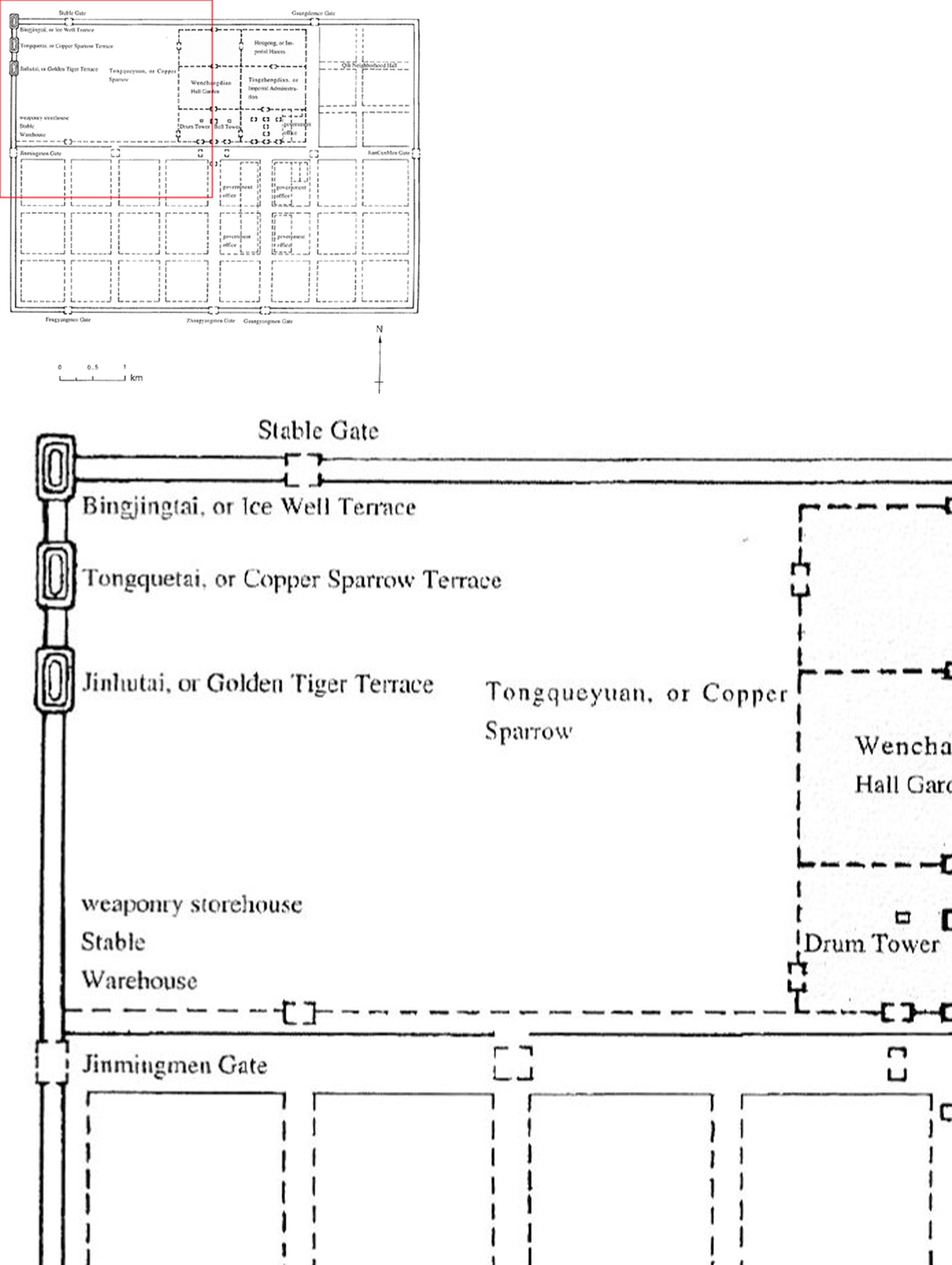

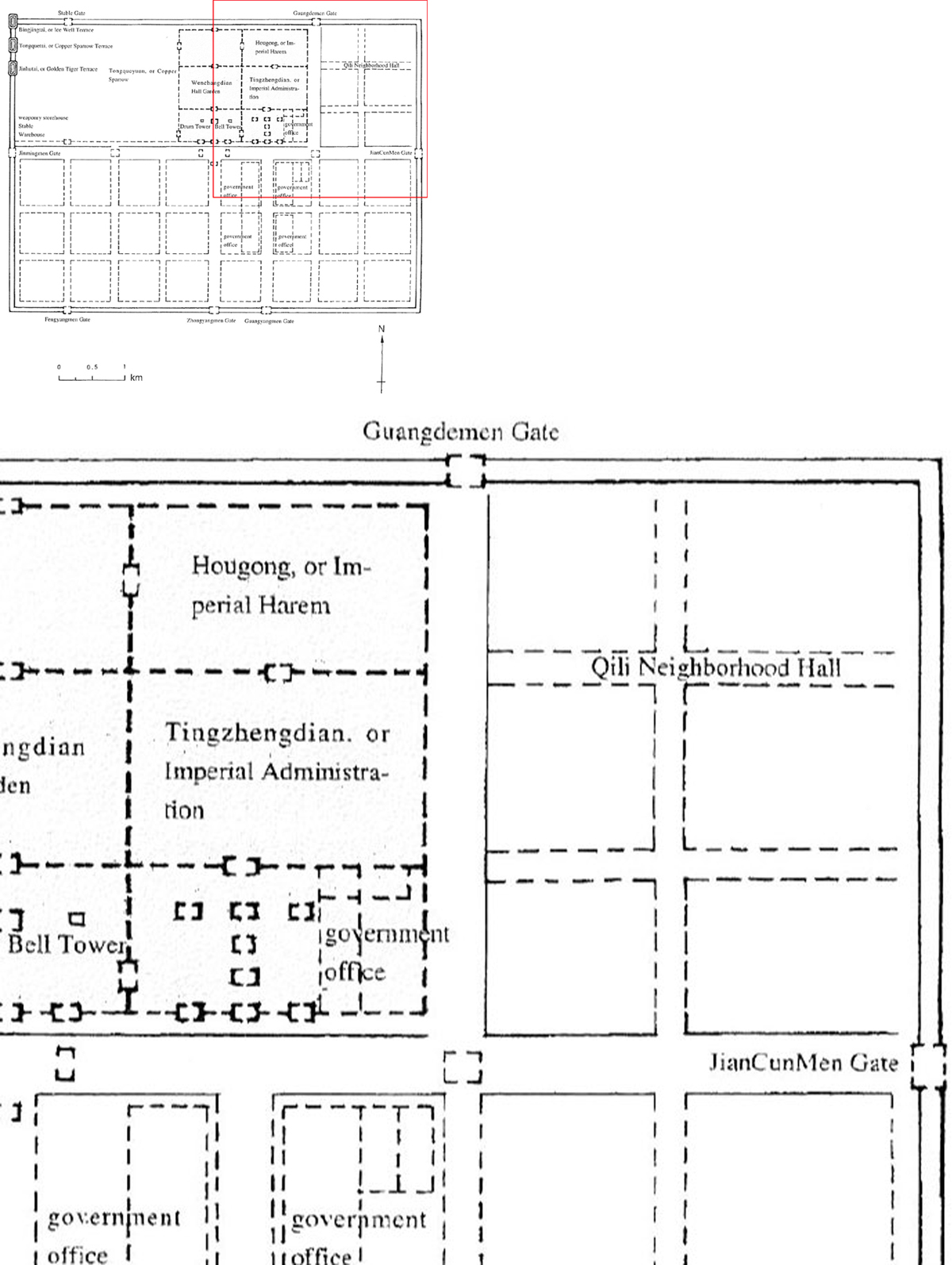

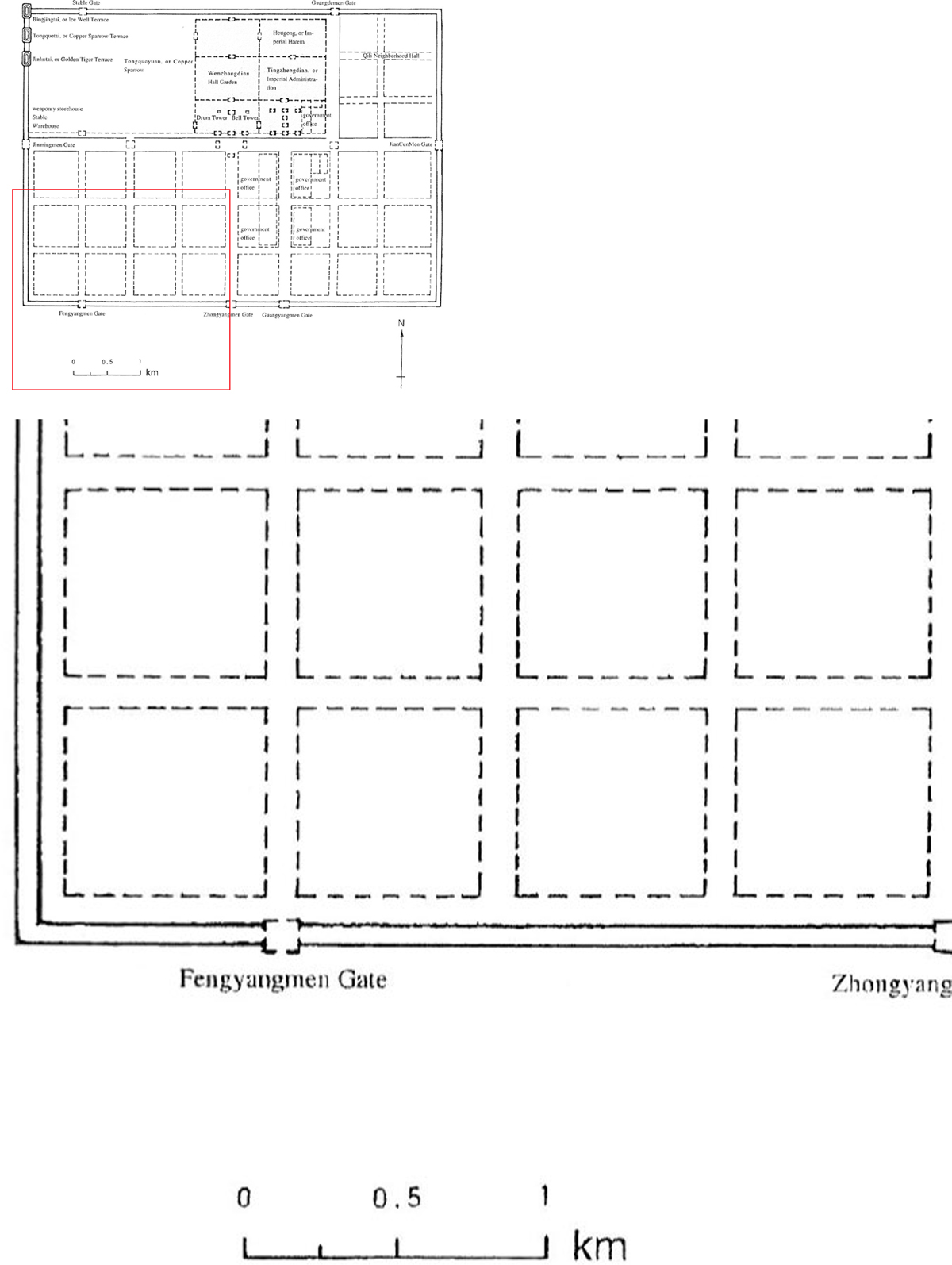

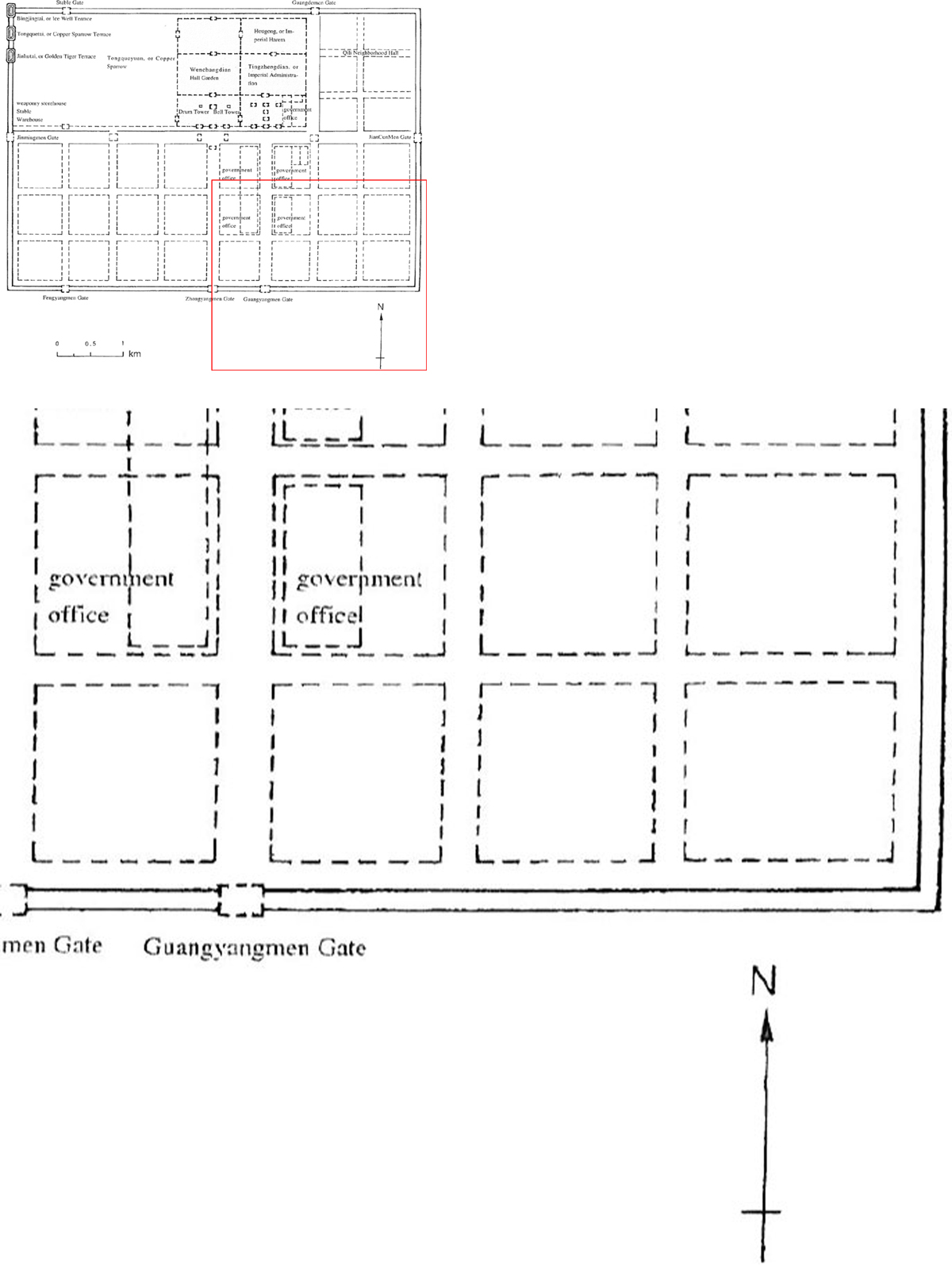

A plan of Ye Cheng, the capital established by Cao Cao, one of the protagonists in the Three Kingdoms Period in AD 213. It was located south of the Zhangshui River in Hebei. The city was built on strict military lines, and a transverse road divided the cheng into two parts. The northern section was where the ruling class had their residences, and included a further wall round the palace cheng and the three Bronze Sparrow Pavilions on top of the north-western wall, which served as places of entertainment in peacetime and as defences in wartime. (After Ishihara Heizo)

As this work concentrates on the fortified cities themselves rather than on the means used to defend or attack them, the reader is referred to my two volumes in the Osprey New Vanguard series, Siege Weapons of the Far East (1) AD 6121300 and Siege Weapons of the Far East (2) AD 9601644 for details of such devices. These should be read particularly in connection with the section that follows on operational history.

The Chinese dynasties and their fortified cities

The ubiquitous presence of walls around Chinese cities, towns and even villages is apparent to the most casual visitor to China. As the author of an article on Chinese architecture for Encyclopaedia Britannica observed many years ago:

Walls, walls, and yet again walls, form the framework of every Chinese city. They surround it, they divide it into lots and compounds, they mark more than any other structures the basic features of the Chinese communities. There is no real city in China without a surrounding wall, a condition which is indeed expressed by the fact that the Chinese used the same word cheng for a city and a city wall; there is no such thing as a city without a wall. It would be just as inconceivable as a house without a roof.

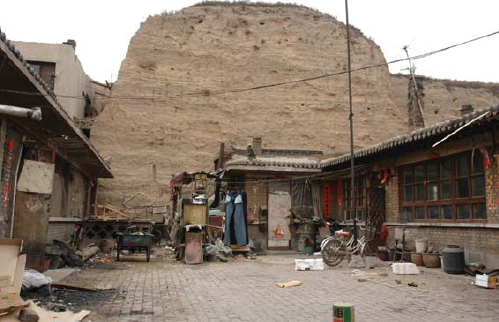

Part of the eastern wall of Datong. A considerable proportion of the circuit of rammed earth walls of this ancient former capital has survived, and may be followed around the city. In most places courtyard dwellings are built directly on to the walls surface.

He goes on to note the presence of a wall around even very small villages, then returns to the situation of the defended city:

Many a city in north-western China which has been partly demolished by war and famine and fire, where no house is left standing and where no human being lives, still retains its crenellated walls with their gates and watchtowers. Those bare brick walls, sometimes rising over a moat, or again simply from the open level ground where the view of the distance is unblocked by buildings, often tell more of the ancient greatness of the city than the houses and temples.

To this observation of bare brick walls may be added the opportunity to see, and even walk along, some considerable remains of rammed earth walls that are an amazing three millennia old. They lie where the Yellow River was to become the cradle of Chinese civilization and are to be found in the Shang dynasty (c. 15201030 BC ) city of Zhengzhou. From the time of the Shang onwards successive dynasties were to be marked by the creation of new capitals, often on sites used by former dynasties, and their fortification by strong city walls. Indeed, the story of the rise and fall of successive dynasties can be told through the history of the capitals they selected. Thus the Shang were overthrown by the Zhou, who expanded their kingdom west of the Yellow River into Shaanxi province, where they made a capital in the vicinity of modern Xian. They ruled through a hierarchy of powerful vassals, whose activities slowly reduced the Zhou power and forced their rulers to move to a new capital at Luoyang in 771 BC , from where later Zhou rulers exercised only a symbolic authority.

Four hundred years of conflict between petty states and kingdoms ensued, to which are given the names of the Spring and Autumn and the Warring States periods. The fighting came to an end with the triumph of Chinas first emperor Qin Shihuang Di in 221 BC , who ruled from Xianyang, just north of Xian, and is best known today for the terracotta army that guards his tomb. The Qin Emperors reign did not last long, and in 206 BC the rebel warlord Liu Bang founded the Han dynasty. He built a completely new capital on the site of Xian, to which was given the name Changan. It took two major efforts to build the wall the first in 194 BC , the second five years later involving the mobilization of tens of thousands of labourers. The resulting wall was an irregular rectangle that was almost square, its perimeter being 25.5km. There were three triple gateways on each side with their own towers. The Han dynasty greatly expanded their domains, until infighting led to problems and the setting up of the Eastern Han dynasty at Luoyang. Changan was abandoned, and was described by a later traveller as overgrown with rank grass, and haunted by foxes, hares and pheasants. Luoyang, however, was quite magnificent, with a rectangular layout measuring 4.3km by 3.7km.

Next page