Fortress 57

The Great Wall of China 221 BCAD 1644

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Steve Noon

Series editors Marcus Cowper and Nikolai Bogdanovic

Contents

Introduction: raiding and trading

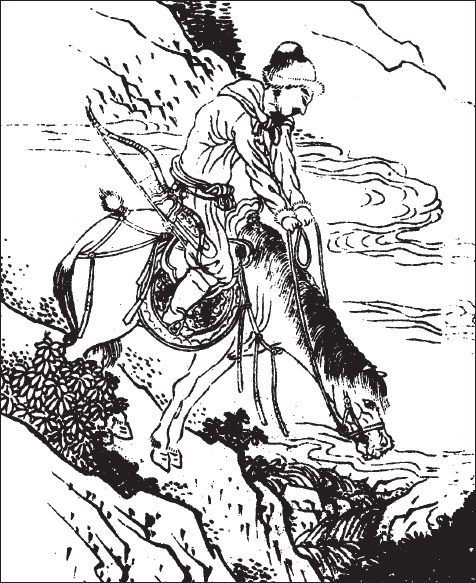

The Great Wall of China owes its existence to the history of the interaction between the settled agricultural communities of China and their predominantly nomadic neighbours to the north. Nearly half of the territory that makes up modern China is desert, mountain or arid plateau, and for much of the countrys history peoples whose culture and languages were very different from those of the ethnic Han Chinese occupied these lands. Some conducted agriculture on a small scale, but the vast majority lived lives that were sustained by what is known as pastoral nomadism. Pastoral means that they herded vast flocks of domesticated animals, mainly sheep, across open grasslands, rather than confining them within corrals and feeding them hay. Nomadism refers to the need to move around to seek renewed pasturelands while the ones they had just left were regenerating. The life of a nomad was a highly mobile one where skills at horsemanship were greatly prized. Children learned to ride at a very early age, and the whole experience of their lives acted as a training for future wars, when rapidly moving mobile units would raid settled communities or engage them in battle; highly skilled mounted archery was the nomads greatest asset.

For 2,000 years the settled agricultural civilization of the Chinese Empire was regularly threatened, harassed, invaded and sometimes even conquered by these northern nomadic tribes, and the reasons why this happened provoked a debate that began centuries ago in the Chinese court and still continues in academic circles today. To the early emperors the nomads were just naturally warlike, uncivilized and even sub-human. The Xiongnu for example, according to a historian of the Han dynasty, had an inborn nature to go off plundering and marauding. Modern historians take a less prejudiced view, and several theories have been put forward to explain the rationale behind nomadic raiding. One approach is to consider the basic incompatibility between settled agriculture and nomadic herding. If the two activities could be carried out in separate areas then there was no possibility of conflict, but if by reason of drought or famine on their native steppes the nomads were forced to seek pastures elsewhere then friction would develop. In desperate times the nomads might even attack sedentary communities for food in order to survive. Unfortunately, not enough is known about the climatic history of the area to prove if this did actually happen.

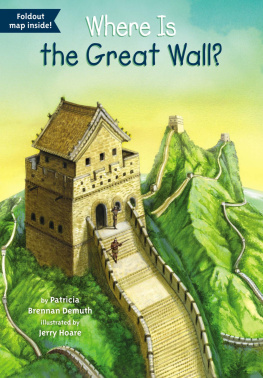

The classic image of the Great Wall of China, as shown in this panorama of the Badaling section in 1987. (Photograph by Ian Clark)

The Great Wall at Shanhaiguan is an impressive fortress complex built round the famous First Pass Under Heaven: a huge gatehouse complex protected by a courtyard. On top of its wide battlements is a majestic gate-tower with a tiled double roof and colourful eaves. This view is from the west.

Other historians have looked at what it was that the nomads actually needed from the Chinese other than food supplies in times of crisis, because certain goods and commodities could only be supplied with great difficulty within a nomadic lifestyle. These items included grain to supplement their diet, and textiles and metal objects such as weapons. There was also a need to trade luxury items to sustain the relationships between nomad rulers and their regional and local chieftains. Trade, in this context, meant more than a simple exchange of goods, and included such mechanisms as intermarriage of royal families, tribute missions and the setting up of border markets. There was also the factor of what the Chinese needed from the nomads. The Chinese heartlands were not suitable for the raising of horses, and cavalry was an essential item in warfare if the nomad armies were to be met on their own terms. When the Chinese were willing to allow such trade to take place, it can be argued, peaceful relationships prevailed. If for any reason these complex trade relations were cut off, and there were several instances in Chinese history when they were, then the nomads might take matters into their own hands.

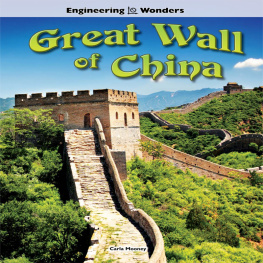

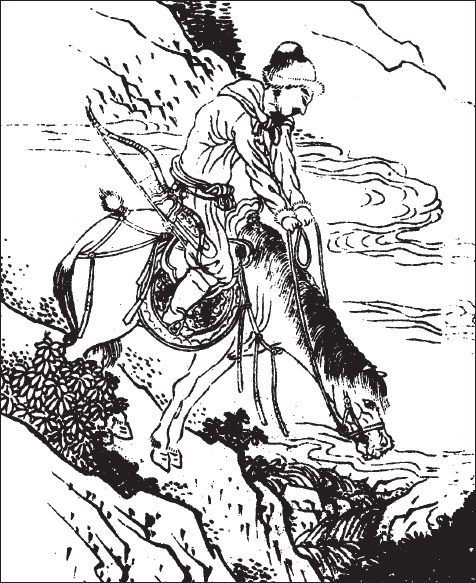

One of the nomad warriors whose raids on China led to the Great Wall being built as one response to the threat they posed. Rapidly moving mobile units would raid settled communities or engage them in battle, where highly skilled mounted archery was the nomads greatest asset.

In other words, the nomads needed either to trade or to raid, and when raiding was seen to be easier than trading, the boundaries between the two activities became blurred. Repeated and unchecked pillaging easily developed into control from a distance, as exemplified by the relations between the Xiongnu and the early Han dynasty. Control from a distance could develop into the occupation of patches of territory, so that the invading forces directed any economic exchange. The culmination of such a process was the conquest of China itself and the setting up of dynasties based on what were already quite sophisticated nomadic empires. This dramatic change happened remarkably frequently in Chinese history from the time of the Wei dynasty, who ruled much of northern China during the 5th and 6th centuries AD . The Kitan Liao dynasty ( AD 9161125) and the Jurchen Jin dynasty (11261234) had their origins in Manchuria, where their predominantly pastoral nomadic culture also included enough elements of settled agriculture to prepare them for the task of governing China through the use of taxation systems and the like. The Yuan dynasty (12791368) was established by Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, who laid the foundations of the vast Mongol empire. The Yuan were overthrown by the native Chinese Ming dynasty, but the Ming were to lose control in 1644 to another northern conquest dynasty: the Qing (Manchu) dynasty, who ruled until 1912 and came from the same ethnic stock as the Jurchen Jin.

This long catalogue of failures by the Han Chinese to defend themselves against the nomads underlines why the control of their northern neighbours, whether by diplomatic or military means, became the chief preoccupation of successive emperors. It is also important to realize that the Chinese did not only have to deal with sporadic raids by loosely organized groups of nomads. The nomad threat was also expressed through several major campaigns conducted against their borders by the armies of well-organized steppe empires who already controlled developed economies. Their ambitions went much further than mere plunder.

The long-lasting threat from the north provided a considerable challenge that was constantly changing and developing. It was never one that could easily be met on purely military terms, because the direct approach of launching retaliatory campaigns into nomadic territory was dangerous and costly. The Han Emperor Wudi achieved some success in 119 BC when he mounted an expedition into the Xiongnu homelands, but there are few other similar examples. Improved weaponry for Chinese infantrymen to enable them to break the impact of a nomad charge was another possible counter-measure, but such small-scale tactics were only effective if the enemy horsemen allowed themselves to get near enough to the Chinese lines. Chinese cavalrymen were sometimes useful against the raiders, but they never attained the nomads levels of skill at horsemanship. A more strategic approach was required, and a historian of the Song dynasty, Ouyang Xiu (100772), recommended the following way of dealing with the nomads: