Campaign 122

Tannenberg 1410

Disaster for the Teutonic Knights

Stephen Turnbull Illustrated by Richard Hook

Series editor Lee Johnson Consultant editor David G Chandler

CONTENTS

This painting entitled The Return of the Crusader by the 19th-century artist Karl Friedrich Lessing, captures two characteristic features of the knights of the Teutonic Order the white mantle bearing a black cross and the full beard.

INTRODUCTION

T he battle that was fought in the fields adjoining the villages of Grunwald and Tannenberg in present-day Poland in the year 1410 was one of the largest battles in medieval European history, and the memory of it is still capable of stirring fiercely nationalist emotions. This is most apparent from the fact that the battle has been given three different names. It is Grunwald to the Polish, Tannenberg to the Germans and Zalgiris to the Lithuanians. The conscious link made in World War I between the conflict of 1410 and the Russo-German battle of Tannenberg in 1914, fought nearby, further fuelled the fiery emotions generated by the battle. This reached its climax with Hitler and Stalin, both of whom saw the battle as a symbol of the supposed struggle between the Germans and the Slavs, between Communism and National Socialism. Both leaders shamelessly twisted and distorted the historical facts for political ends and to conform to their views of world history.

This book attempts to be a concise and unbiased account of the battle of Tannenberg/Grunwald, the campaign that led up to it and its long aftermath. It is a remarkable story, and almost unique in military history in that Tannenberg, which was unquestionably the decisive battle of the 50-year-long war between the Teutonic Order and the united kingdom of Poland/Lithuania, was fought at the beginning of the conflict and not at its end. There can also be few other examples in history of a battle so decisively won and a subsequent campaign that so singularly failed to achieve its aims. Despite their crushing victory at Tannenberg, the Polish/Lithuanian army failed to capture Marienburg, key fortress and capital of the Teutonic state.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

The battle of Tannenberg/Grunwald involved three armies: those of the kingdom of Poland, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Prussian state of the Teutonic Order. Although only a relatively small proportion of their army were actually fully armoured knights, I have employed the commonly used title of Teutonic Knights as a general term signifying the total fighting force of the Teutonic Order.

The Teutonic Knights

Throughout their stormy history, and long after their eventual secularisation in 1525, the brethren of the Teutonic Order have always been the most controversial brotherhood to call themselves Knights of Christ. The Order was known as the Servants of St Mary of the German House in its oldest set of rules. It had its origins in the siege of Acre in 1190 during the Third Crusade. German merchants from Bremen and Lbeck established a makeshift field hospital to tend the numerous sick and injured crusaders from the large German contingent. The brethren were committed to caring for the sick and assisting in the defence or recovery of the holy places in a similar fashion to the more numerous members of the Knights Templar and the Knights Hospitaller. In appearance the Teutonic Knights were distinguished from their sister orders by wearing a black cross upon a white robe and mantle. By 1197 the Order had received a charter of incorporation from the Pope, and when the German Emperor Frederick II took the cross in 1215 the Orders fortunes made a marked improvement.

Teutonic Knights on the Prussian Crusade, the venture for which they were invited into Poland in the first place.

In the face of Muslim resurgence, however, and domination by its two more powerful sister orders the Teutonic Order found itself unable to expand in the Holy Land. This and its distinct national identity had led to it developing a particular connection with Germany, and the Orders attention shifted away from the Holy Land. They first answered a request for help from King Andrew of Hungary, whose Transylvanian provinces were being attacked by the warlike Cuman tribes. The Teutonic Knights soon proved to be more of a nuisance than the Cumans, as having defeated the tribesmen they set up a colony of their own. They became so fiercely independent that the Hungarians described the Order as like a viper in the bosom. Alarmed at the German colonisation King Andrew eventually resorted to force in order to expel them.

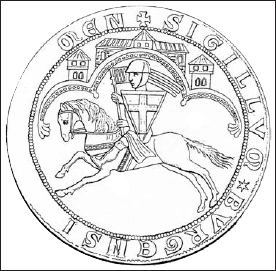

Mounted Teutonic Knight as depicted on the municipal seal of Kulm (Chelmno) c. 1300.

As their Transylvanian adventure was collapsing, however, the Knights received another request for military and religious assistance from a Polish nobleman called Duke Conrad of Masovia. He had found himself unable to cope with the heathen Prussians on his northern borders who threatened his communications with the Baltic and were proving almost impossible either to conquer or convert. The Teutonic Order therefore entered Poland for the first time in 1222 at the express invitation of a Polish dignitary. In return for their services the Order would be granted the territories of Kulm (Chelmno) along the river Vistula (Wisla), and any further territories they conquered in the course of the operation. This was a repeat of the conquest and settlement scenario in Transylvania, but this time with official approval. The Orders Grand Master, Hermann von Salza, immediately recognised the opportunity he had before him and, with the support of Emperor Frederick II, the Pope issued the Golden Bull of Rimini in 1226, which set out in minute detail the constitution of the future state that the Order already intended to win for themselves.

Kwidzyn (Marienwerder), one of the greatest of the Teutonic castles.

A fresco, formerly in the cathedral of Knigsberg, depicting knights of the Teutonic Order.

Thus began the Teutonic Knights Prussian Crusade, and within a few years the inhabitants of the lands around Kulm had been converted. In 1230 Duke Conrad of Masovia kept his word and handed over the conquered territory to the Order. The Grand Master, always the diplomat, astutely had the prize declared the property of St Peter and the Order continued its territorial expansion at the expense of the pagan Prussians. In 1231 their army crossed the Vistula (Wisla) and within a few years the Orders first castles began to appear. Thorn (Torun) was built in 1231, Marienwerder (Kwidzyn) in 1233 and then Elbing (Elblag) secured the line of the Vistula in 1237. Also in 1237 the Sword Brothers, a rival military order with the patronage of the Bishop of Riga, combined with the Teutonic Order. Their territory in Livonia became an autonomous province of the Order so that by the time Hermann von Salza died in 1239 his Teutonic Knights controlled almost 100 miles of the Baltic coast in addition to a considerable area of the interior.

Next page