First published in 1942

Reissued in 1969

by George Allen & Unwin Ltd

This edition first published in 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 4RN

Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada

by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

1942, 1969 George Allen & Unwin Ltd

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Publishers Note

The publisher has gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of this reprint but points out that some imperfections in the original copies may be apparent.

Disclaimer

The publisher has made every effort to trace copyright holders and welcomes correspondence from those they have been unable to contact.

A Library of Congress record exists under LC control number: 68009588

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-70681-0 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-315-88726-5 (ebk)

First published 1942

All rights reserved

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN BY

STEPHEN AUSTIN AND SONS, LTD., HERTFORD

The German original of this work, entitled

Das deutsche Ordensland Preussen, was published in 1862, the year when Bismarck became minister-president of Prussia. It now appears for the first time in English.

Translators Preface

Heinrich von Treitschke, the author of this very remarkable study of the colonization of Old Prussia by the Teutonic Knights (substantially an account of the origins of Prussianism), was born at Dresden in 1834 and died at Berlin in 1896, before completing his most famous work, History of Germany in the Nineteenth Century, which he carried on only to 1847. That was translated into English and published here during the war of 19141918, in seven volumes. The present essay was penned in 1862. In youth Treitschke had liberal leanings which made it impossible for him to begin his professorial career in Saxony, and he was still unacademic when he wrote Das deutsche Ordensland Preussen. But his liberalism was never more than skin-deepnever radical. Besides being an enthusiastic admirer of Prussianism, he was bitten by the antisemitism which has long been one of the curses of Germany. The fact that the two most prominent German socialists among his contemporaries in youth, Marx and Lassalle, were both of Jewish extraction, may have contributed to Treitschkes hatred of socialism. But antisemitism apart, there was enough ground for dislike of national socialism, after the fashion of Lassalle, and international communism, after the fashion of Marx, in a man who idolized a State which should be organized to protect and further the interests and to diffuse the national civilization of a possessing classwith a modicum of liberal respect for the well-being of workers and peasants. (Of course Treitschke, who died twenty years before the recent Russian revolution, would never have phrased his Statism in any such terms.)

Still, the work here translated bears some traces of the liberalism which, in the end, Treitschke forsook, and is not entirely free from criticism of the Germans. But it exemplifies the writers most salient characteristics: a worship of the State; belief in the fundamental excellence of the German race and of German ways (a belief which made him a forerunner of Nazism); and a conviction that, by divine dispensation, it had been the mission of the Hohenzollerns, working through Prussia, to unify Germany and ensure the unrestricted predominance of those who are now usually spoken of by Germanophils as Nordics or Aryans. What he would have thought of the second Emperor William in later days, and still more what he would have thought of Adolf Hitler, may be open to question; but the study of the late-medieval Ordensland has a strong bearing on the present war, which we will lightly touch upon after a few quotations to exemplify the points we have been making.

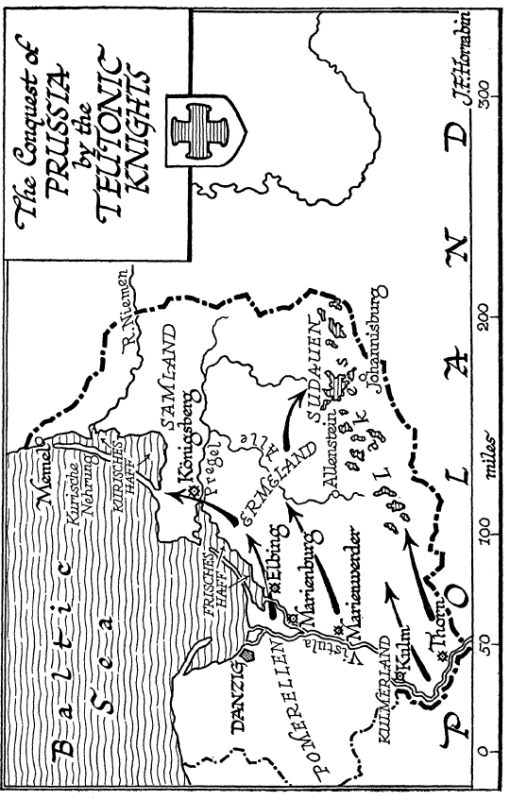

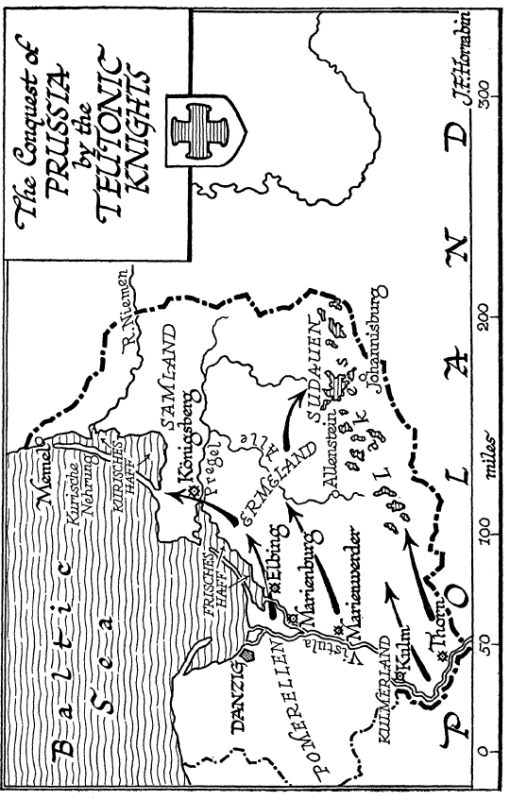

To explain the need for his book, Treitschke writes (p. 18): There is hardly even an outline sketch to convey to the mind of a South German boy an intimation of the most stupendous and fruitful occurrence of the later Middle Agesthe northward and eastward rush of the German spirit and the formidable activities of our people as conqueror, teacher, discipliner of its neighbours.

He writes (p. 19) of the impossibility of understanding Germany unless one is familiar with those pitiless racial conflicts whose vestiges... live on mysteriously in the habits of our people.

The Teutonic Knights (p. 20) were not only swashbuckling soldiers, but also thoughtful administrators; not only abstemious monks, but also venturesome merchants, and (still more remarkable) bold and far-seeing statesmen.

He speaks (p. 21) of the supreme value of the State, and of civic subordination to the purposes of the State, which the Teutonic Knights perhaps proclaimed more loudly than do any other voices speaking to us from the German past.

Here are two interesting criticisms (p. 22): Kindliness is wrongfully declared to be an essential virtue of the Germans; and (p. 39) the full harshness of our national spirit was displayed when conquerors endowed with the triple pride of Christians, knights, and Germans had to form front against the heathen.

Now for his views on colonization (pp. 5556): Thus did our people, upon this narrow stage, forestall those two main trends of colonial policy which were subsequently to guide Britain and Spain with equal success upon the vast expanses of America. In the unhappy clash between races inspired by fierce mutual enmity, the blood-stained savagery of a quick war of annihilation is more humane, less revolting, than the specious clemency of sloth, which keeps the vanquished in the state of brute beasts while either hardening the hearts of the victors or reducing them to the dull brutality of those they subjugate.