Droysen

__________and___________________

The Prussian School

of History

Droysen

______________and___________________

The Prussian School

of History

Robert Southard

Copyright 1995 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre

College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University,

The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College,

Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University,

Morehead State University, Murray State University,

Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University,

University of Kentucky, University of Louisville,

and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8131-1884-0 (cloth: alk. paper)

This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

| Member of the Association of

American University Presses |

Contents

Preface

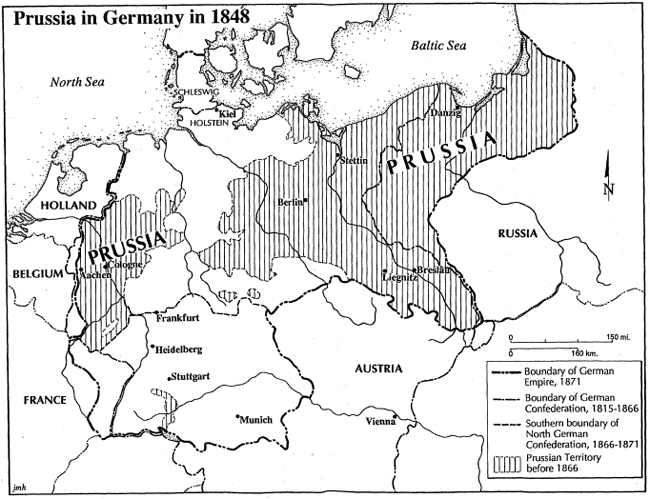

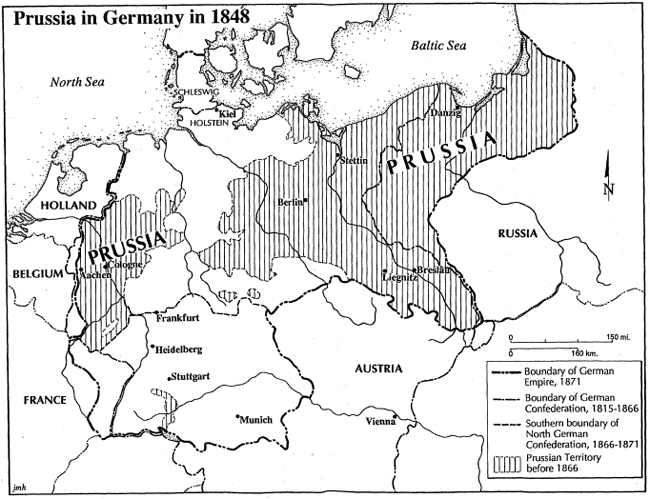

This is a book about how the Prussian School of History came to be. Because that process occurred bit by bit and over time, I have been old-fashioned enough to resort to historical narration. Because these historians were men of ideas with a lot to say, I have explained their ideas as fully and fairly as I could. That kind of intellectual history is also a bit old-fashioned, but some ideas deserve close scrutiny. Their ideas do, because, though sometimes wrong, they are always interesting. More to the point for a historian, their ideas were strongly influential. Granted, that influence was exercised within an elite, but Imperial Germany was an authoritarian state, and, by definition, authoritarian states are ruled by elites. I was attracted to the study of this subject, in the first place, because I thought it would help in understanding the Germany that was partially created in the first unification of 1866 and 187071. I was, and remain, attracted for another reason. The formation of this school is a striking case in point of both the indeliberately self-serving quality of ideology for intellectuals in politics and of the essentially religious nature of some modern nationalism.

I have some intellectual debts that I especially want to acknowledge. I learned from the late Leonard Krieger to ask about the politics of history in Germany. Emile Karafiol taught me a great deal about how to read theoretical discourse. William H. McNeill taught me the need for an architectonic perspective and, always, the importance of writing punctually and clearly. My colleagues Peter Cline and Gordon Thompson read and critiqued this manuscript. I have tried to follow their advice. The late Marian Shelby, a teacher and friend for many years, also read it and offered judicious suggestions. My wife, Edna Southard, repeatedly took time away from her own demanding schedule of research and publication to read and critique what I wrote. Art historys loss was, I hope, intellectual historys gain. My gratitude and appreciation are surpassing, and I dedicate the book to her and to David and Jared. I am grateful to Earlham Colleges Professional Development Fund for its support and for the confidence it showed in my work. I especially want to thank the library staffs at the Frankfort Universittsbibliothek, the Marburg Universittsbibliothek, the Newberry Library of Chicago, the Regenstein Library of the University of Chicago, Lilly Library of Indiana University, and, of course, Earlham Colleges own Lilly Library. To Cheri Gaddis of Earlhams Social Science Division special thanks are due for friendliness and computer expertise in manuscript preparation.

Introduction

The Prussian or Little German (kleindeutsch) School of history is normally defined in terms of the political program that its adherents advanced: the unification of Germany, without Austrias German provinces, as a constitutional monarchy under the Hohenzollern. This definition by political program is understandable. Their major political outlook is more recognizable than the theories that underlie it, and in their mature works, historians such as Johann Gustav Droysen (180886), Heinrich von Sybel (181795), and Heinrich von Treitschke (183496) were stridently pro-Prussian in their German nationalism. Moreover, they enjoyed the celebrity that comes from being on the winning side. Along with other colleagues, they had predicted and, afterward, justified the national unification that Bismarck actually accomplished in 1866 and 187071. Finally, they were politically important. As educators at elite universities and writers of histories for an educated national readership, they helped give intellectual respectability to the nationalism of Wilhelminian Germany. Those are persuasive reasons for grouping them in terms of the political content in their histories, but this definition comes at some cost. It partly overlooks what they thought they were doing. As they viewed matters, their expectant demand for unification under Prussias dynasty was only one of several major political goals that rested less on their personal wishes than on what they thought was a durable structure of historical theory. In any case, to define them chiefly in terms of the role they anticipated for Prussia stresses what their political program became while ignoring what it originally was until well into the revolutionary year 1848. To reduce their careers to that single, though very important, political demand is like reviewing a book after reading only its conclusion.

Droysen and his colleagues were undeniably political advocates, but they rationalized their advocacy with a conception of history that, to their minds, kept them from being what their opponents often accused them of being, propagandists disguised as professional historians. That is, they were political historians in a peculiarly intense sense of the term. In principle, as in practice, they eliminated any firm distinction between scholarship and partisanship by thinking of history as progressive, of progress as inevitable, and of inevitability as good. In consequence, present and future politics seemed merely the necessary continuation of previous history and their advocacy merely the logical extension of their interpretation of bygone events. To state the case differently, past and present were points on a continuum of progress such that their understanding of the past and their engagement in the present were functions each of the other. They did not believe that this quality made their histories tendentious, though it often did, and in fact some of their works were genial enough still to be read with profit. In the spectrum of German politics, they were constitutional moderates, always a bit to the right of center, but in one important respect they resembled the Marxists (who took some of their key ideas from the same sources as these historians did). They denied that a politically neutral history was either possible or desirable, because sound scholarship could find where history was moving and thus chart the right political course to follow. By the same token, the observable movement of history in the present told them what questions to pose of the past.