Contents

About the Author

Colin Thubron is an acknowledged master of travel writing. His first books were about the Middle East Damascus, Lebanon and Cyprus. In 1982 he travelled in the Soviet Union, pursued by the KGB. From these early experiences developed his great travel books on the land mass that makes up Russia and Asia: Among the Russians, Behind the Wall, The Lost Heart of Asia, In Siberia and Shadow of the Silk Road. He has won many awards.

Colin Thubron is also a prize-winning novelist. He lives in London.

ALSO BY COLIN THUBRON

Non-fiction

Mirror to Damascus

The Hills of Adonis

Jerusalem

Journey into Cyprus

Among the Russians

The Lost Heart of Asia

In Siberia

Shadow of the Silk Road

Fiction

The God in the Mountain

Emperor

A Cruel Madness

Falling

Turning Back the Sun

Distance

To the Last City

Authors Note

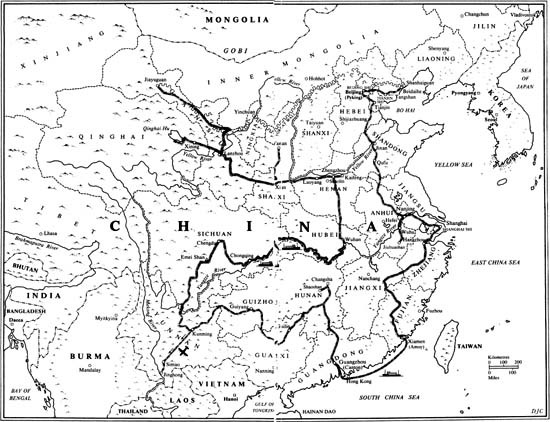

The identity of several people in this book has been disguised, in case harsher times return. The journey recorded here took place over a single autumn and early winter, but incorporates a few episodes from an earlier, briefer visit to China. So the book is a compression of experience, and inevitably omits many encounters made barren by peoples reticence or by my poor Mandarin.

The spelling throughout follows the modern, pinyin system of romanisation, except for a handful of names with well-known English equivalents (such as Tibet, Canton). So Peking becomes Beijing, Mao Tsetung and Chou Enlai become Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, etc.

For my Father

with love and admiration

Behind the Wall

A Journey Through China

Colin Thubron

1. The Capital

AFTER THE SHORT night, the sun rose upon a country of such desolate strangeness that the woman sitting beside me leaned forward with her hands tensed over her stomach and let out a constricted Ohhh! For three hours we sat craning at the aeroplane window while the Karakoram and the western Himalaya glimmered and died among camel-coloured mountains, the mountains merged into hills and the hills burrowed at last into the Taklimakan Depression, the deepest waterless region on earth. Momentarily to the north the blades of the Tian Shan erupted from cushions of cloud, turned pink and harmless by the climbing sun. Then these too vanished, and we were flying along the southern fringes of Mongolia and the Gobi desert. And still, in this country of a quarter of mankind, we saw no sign of life.

Her nations vastness seemed slightly to have appalled the woman. She said: Are you travelling alone? She was young, conventionally pretty. Only her stained teeth suggested some history poorer than her dress. She wondered where I was going in China, and covertly why.

But I could scarcely answer why. The opening-up of China had stirred me unbearably. It was like discovering a new room in a house in which youd lived all your life. Five years ago the country had been almost inaccessible. Today nearly the whole land could be penetrated by a traveller going alone. More than two hundred and fifty different regions and cities had fallen suddenly open, and the traffic of trains, boats and buses between them offered ways of vanishing into the wilds. I had plans for criss-crossing classical China (no Tibet, no Manchuria) almost at random for over ten thousand miles, of plunging into the tribal regions abutting Burma along the Mekong river, of reaching the eastern Himalaya and following the Great Wall to its end in the far north-west.

But to the woman I only said, a little ashamed (since no Chinese could see so much of her country): I want to visit Beijing and Shanghai, and maybe Ill go up the Yangtze, then to Canton and....

She smiled her set smile. Perhaps she was wondering what the foreigner could ever understand of her nation this Westerner with his boorish rucksack (Id dropped it on her feet) and his failure to travel in a group. What could he ever learn?

Even in childhood that time of intense, dissociated images my idea of China had been contradictory and distorted. Its colours even then were subtle. It lay embalmed in distance and exotic etiquette. Chinese atrocities were chattered about at my prep school during the Korean War. Have you heard the latest Chinese torture? my classmates would demand, before twisting somebodys arm or neck in a novel direction. The Chinese, after all, were stunted and yellow and looked alike. Their multitudinous numbers lent them anonymity. They werent quite human. Yet for me their landscape resolved into a mist of waterfalls and twisted pines the Shangri-la of the scroll-paintings and the idea of a Chinaman harboured a paradoxical element of the ridiculous (something to do with pigtails and The Nutcracker Suite, I think). In any case, China was too distant to be threatening. It was and remained a luminous puzzle.

Peoples images of countries are rich in such buried sediment, which goes on haunting long after experience or common sense has diluted it. And by now as we floated above the wrung-out steppes of the Gobi other strata had overlaid the first. In the anarchy of the Cultural Revolution, between 1966 and 1976, the Chinese people had not merely been terrorised from above but had themselves tens of millions of them become the instruments of their own torture. The land had sunk into a peculiar horror. A million were killed; some thirty million more were brutally persecuted, and unknown millions starved to death. Yet it was less the numbers which appalled than the refinements of cruelty practised in one province alone seventy-five different methods of torture were instituted and I never thought of the country now without being dogged by a tragic question-mark.

The woman was rummaging in her handbag. In the seats behind us a conclave of Beijing businessmen sprawled, their shirt collars open, their eyes closed. I was seized by the foolish idea that each one of them was withholding some secret from me some simple, perfect illumination. Because that is the foreigners obsession in China. At every moment, round every corner, the question Who are they? erupts and nags. How could they be so led? How could they do what they had done? And had they ever changed this people of exquisite poetry and refined brush-strokes, and pitilessness?

A billion uncomprehended people.

Beneath us now, where the last hills tilted south-eastward out of Inner Mongolia into the huge alluvial basin of the Yellow River, I could see the divide between plateau and plain, agricultural hardship and sufficiency, drawn vertically down the earths atlas with the precision of a pencil-stroke. To the west brown, to the east green.

Within half an hour we would be landing in Beijing old Peking and as if these last airborne minutes might liberate us from inhibitions, I started talking with the woman about the Cultural Revolution. She turned quizzically to me and asked: What do you think of Mao Zedong in the West?

I said we thought him a remarkable leader, but inhumane.

She said coldly: Yes. He made mistakes.

Mistakes! He had caused more than sixteen million deaths. Sometimes he had acted and talked about people as if they were mere disposable counters on an ideological gameboard. And she talked of mistakes. It was how the Russians spoke of Stalin. I said tightly I felt this might be my last (and first) chance to vent anger in China: All that suffering inflicted on your people! How can you forgive that? Then I added: I think he became a monster.