T HIS JOURNEY by car through European Russia took place in the summer and fall of 1980 towards the end of the grayest era in Soviet history: the long, stagnant reign of President Brezhnev. At that time almost nobodyin either the Soviet Union or the Westpredicted what was soon to happen. Now this journey, unusual in its day, seems to belong to remote history.

Yet the fascination of a peoples character survives political change. In this sense the Russia I encountered then is recognizable today. Brezhnevs USSR, and Stalins before it, looms like a haunting hinterland behind the lives of ordinary Russians, who remain the offspring of the complex world into which I blundered twenty years ago.

Later journeys took me deeper into these lands I had been brought up to fear, and a further three books charted them: Behind the Wall on China still shadowed by the Cultural Revolution; The Lost Heart of Asia on the Islamic republics emerging from the ruins of the Soviet Union; and In Siberia on Russias eastern wilderness. Among the Russians is the first of this quarter, and perhaps the most innocent: a lone Westerner travelling into a Soviet world which still seemed impregnable.

C.G.D.T.

London, 2000

I HAD BEEN afraid of Russia ever since I could remember. When I was a boy its mass dominated the map which covered the classroom wall; it was tinted a wan green, I recall, and was distorted by Mercators projection so that its tundras suffocated half the world. Where other nationsJapan, Brazil, Indiaclamoured with imagined scents and colours, Russia gave out only silence, and was somehow incomplete. I grew up in its shadow, just as my parents had grown up in the shadow of Germany.

Journeys rarely begin where we think they do. Mine, perhaps, started in that classroom, where the green-tinted mystery hypnotized me during maths lessons. Already questions rose in the childs mind: why did this country seem stranger, less explicit, than others? Why was it untranslated into any precise human expression? The questions were half-formed, of course, but the fear was already there.

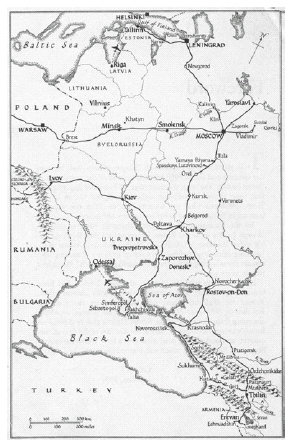

Perhaps it was because of this that thirty years later the land glimmering eastward from the Polish frontier struck me as both familiar and foreboding. It flowed away in an undifferentiated calm, or rose and fell so imperceptibly that only the faintest lift of the horizon betrayed it. I saw nobody. The sky loomed preternaturally vast. The whole world seemed to have been crushed and flattened out into a numinous peace. My car sounded frail on the road. For three hours it had been disembowelled by border officials at Brest, and its faultily-replaced door panels rasped and squealed as if they enclosed mice.

Even now I was unsure what drew me into this country I feared. I belonged to a generation too young to romanticize about Soviet Communism. Yet nothing in the intervening years had dispelled my childhood estrangement and ignorance. My mind was filled with confused pictures: paradox, clich. Russia, wrote the Marquis de Custine in 1839, is a country where everyone is part of a conspiracy to mystify the foreigner. Propaganda still hangs like a ground-mist over the already complicated truth. Newspapers, until you know how to read them, are organs of disinformation. The arts are conservative or silent. Even in novels, which so often paint the ordinary nature of things, the visionaries and drunks who inhabit the pages of nineteenth century fiction have shrivelled to the poor wooden heroes of modern socialist realism. It is as if a great lamp had been turned down.

As for me, I was entering the country too impatiently to be well equipped. I spoke a hesitant Russian, but had read very little. And I was deeply prejudiced. Nobody from the West enters the Soviet Union without prejudice. I took in with me, as naturally as the clothes I wore, a legacy of individualism profoundly different from anything east of the Vistula.

But I think I wanted to know and embrace this enemy I had inherited. I felt myself, at least a little, to be on his side. Communism at once attracted and repelled me. Nothing could be more alluring to the puritan idealist whose tatters (I suppose) hung about me as I took the road to Minsk; nothing more disquieting to the solitary. All my motives, when I thought about them, filled up with ambiguity. Even my method of travel was odd. The Russians favour transient groups and delegations, which are supervised in grandiose hotels. But I was going alone, in my own car, staying at campsites, and planned to cover ten thousand miles along almost every road permitted to me (and a few which were not) between the Baltic and the Caucasus. My head was swimming in contradictory expectations. A deformed grandeur still hovered about this nation in my eyes.

So for more than two hundred miles between Brest and Minsk, I travelled in a state of nervous fascination. There was almost nothing else on the road: dust-clogged lorries carrying wood, cement, cattle; a rare bus; and once a truck packed with frosty-eyed Brueghel peasantry. Every twenty miles or so, in glass and concrete checkpoints raised above the highway, grey-uniformed police fingered their binoculars and telephones. The land was haunted by absencesno advertisements, no pylons, often no telegraph poles. The cluttered country of industrial Europe was smoothed out into a magisterial stillness. Grasslands, farmlands, forests. All huge, all silent. The eye could never compass any one of them. The forests, in particular, looked deep and unredeemed. They lapped against fields and roads in rich, deciduous masses of oak, beech, silver birch. This was Belorussia, White Russia, a state of rye and timberland which stretched half way to Moscow. The deadening pine forests still lingered about its pastures and stencilled every horizon in a line of coniferous darkness.

I gazed at all this with the passion of a newcomer, and scribbled it in a diary before I should forget the feel of ordinary, important things. These first hours shone with a peculiar intensity. In the fields of potato and alfalfa, labourers moved through a soft July sunlightmen and stout women in headscarves wielding billhooks and pitchforks. No collectivized glamour, no tractors or combine harvesters intruded into the sodden ritual of their haymaking. Instead, where marshy fields elbowed through the forests, black and white cattle grazed in isolated herds, and troops of herons paced nonchalantly across the meadows.

After a hundred miles I stopped the car and lay on the verge among butterflies and lupins. The country was steeped in silence. In this limitless terrain, details of plant or insect shone with the exposed distinctness of things seen in the desert. A dragonfly clattered onto my knee. Bright yellow toadflax squeezed up between my fingers. They were obscurely comforting.

But I was conscious above all of the stunned desolation which seems to permeate these plains. It has to do, I think, less with their actual povertysandy soil, poor drainagethan with the inarticulate vastness of which they form a part. Without the nearness of towns or the presence of hills, the sky takes on a terrible passive force. Stand anywhere here, and three-quarters of your field of vision is engulfed by it, adding a pitiless immensity to the size of the land. The sun and clouds hang permanent and immobile in its blue. They curve above you like a Tiepolo ceiling. Everything beneath is exposed. The weather itself assumes a threatening, total quality, so that the earth can momentarily wither under a flagellating sun, and rain burst like a cataclysm. Above all, peopletheir houses, traffic, cattlegrow pitifully incidental. The villages I passed generally stood far off the roadwooden cottages with asbestos or tin roofs pitched steep against snow. They were small, abstracta civilization sketched puny in the fields, like a language I didnt know. Its people, it seemed, were not enclosed and nurtured, made private or different by the folds of valleys and mountains. They were figures in a landscape, living under the naked sky in the glare of infinity.